The connection between an ancestor worship of the Luo Yue people and the motifs painted in the Huashan rock art was already mentioned by Qin Shengmin and others (e.g. Qin et al. 1987: 175). Yet, there is much more that can be said about how the motifs are related to the Luo Yue religion and also about how the spiritual traditions of the artists can be linked to the location of the site itself. The aim of this article, therefore, is to search for the spiritual traditions that the ancient Luo Yue people may have had and to propose a possible explanation of why this very site was chosen to produce this grandiose rock art panel. In order to approach this information, it is proposed here that it is worthy to reexamine in depth the religious beliefs and traditions held by the ethnic groups believed to be the Luo Yue’s descendants.

There are several groups believed by scholars to be the Luo Yue’s descendants: the Zhuang people, mainly living in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of China; the Viet (also called ‘Kinh’) people, the ethnic majority of Vietnam; and the Muong people, an ethnic minority inhabiting the mountainous region of northern Vietnam (Dao 1976: 233). Conventionally, Chinese scholars who study the Huashan rock art only resort to the Zhuang culture and rarely look beyond the Sino-Vietnamese border to take the culture of these Vietnamese groups into account. Therefore, the discussion below will not limit itself to the Zhuang culture as a possible cultural context for the Huashan rock art site. My approach will be a step forward by incorporating some research on Vietnamese culture and other relevant Southeast Asian cultures.

Based on historical records and the studies of modern Zhuang and Muong people, scholars defined the Luo Yue’s religion as animism and ancestor worship (Qin 2006: 256; Dao 1976: 235). Animism is a religion focused on the belief that nature includes spiritual beings, sacred forces and similar extraordinary phenomena. It encompasses the belief that souls exist not only in humans but also in natural objects, including animals, plants, rocks, geographic features such as mountains or rivers, or other entities of the natural environment (Birx 2006: 80). Ancestor worship is also referred to as a form of ancestral cult. Beliefs of this cult centre on the ability of the dead to protect kinsmen in return for worship from them (Birx 2006: 72). The two forms of religion are not incompatible in the same society, although anthropology has seen these as disparate religions when, in fact, they are just two different religious practices. Both animism and ancestor worship still exist today among the Zhuang people, Muong people, and some other ethnic groups related to the Luo Yue people.

In Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, the very diffuse topography has made the Zhuang peoples live in relatively small groups. Environmental and cultural diversity has promoted different spiritual practices. The local animistic cults address a rich variety of spiritual beings, and there is no clear division between such spiritual beings and local gods (Yu 2004: 10). Chinese scholars have categorised the spiritual beings and gods worshipped by the Zhuang people into mainly four groups, each with a most important god representing the rest, as listed below (Liao 2002: 6).

| Religious Beliefs Among the Yuo Luo's Descendants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Thunder: represents all things related to the sky, such as celestial beings and all types of weather. | |||

| (2) Water: represents all things related to the earth, such as stone and soil, river and fire. | |||

| (3) Flower: represents fertility. | |||

| (4) Frog: represents all animals, especially those have a close relationship with agriculture. |

In Zhuang people’s mythology, the four gods are closely related by another god, Baeuqloegdoz, the god of ancestors. Baeuqloegdoz, brother of the thunder god and the water god, uncle of the frog god, and husband of the flower goddess, is unique in his human nature, as he is considered by the Zhuang people today to be the great ancestor and the first Zhuang individual. Below, the ethnographic sources regarding the three elements of thunder, water and frog, along with the god of ancestors, and how scholars have related them to the depictions in the Huashan rock art site are explored. It is argued that rather than the rock art site being related to just one of the three elements, as seems to be suggested by current scholarship, the site is actually related to all three elements.

The ethnographic sources

It is not difficult to understand why thunder has been viewed as the mightiest god ruling the sky. According to scholars, the ancient Luo Yue culture is closely associated with rice cultivation, and even the name ‘Luo’ was derived from one type of paddy field (called ‘Luo field’ in historical records) developed by them for growing rice (Qin 2007: 14). Agricultural production is highly dependent on weather, climate and water availability. In south-western China, the humid subtropical climate causes thunder to be popularly perceived as a mysterious weather phenomenon, which always brings about abundant rainfall, essential for a good harvest (Liao 2002: 68). Therefore, in antiquity, thunder was deified as the god in charge of weather and sky. Today, some Zhuang groups in the Zuojiang River valley still pay homage to the temples of the thunder god and, if prolonged droughts occur, rituals will be held to ask the thunder god for rain (op. cit.: 74). Actually, because agriculture still plays the most important part in the local economy, ceremonial rituals devoted to the thunder god have been extensively practised among the Zhuang people (op. cit.: 42).

Thunder in the Huashan rock art site

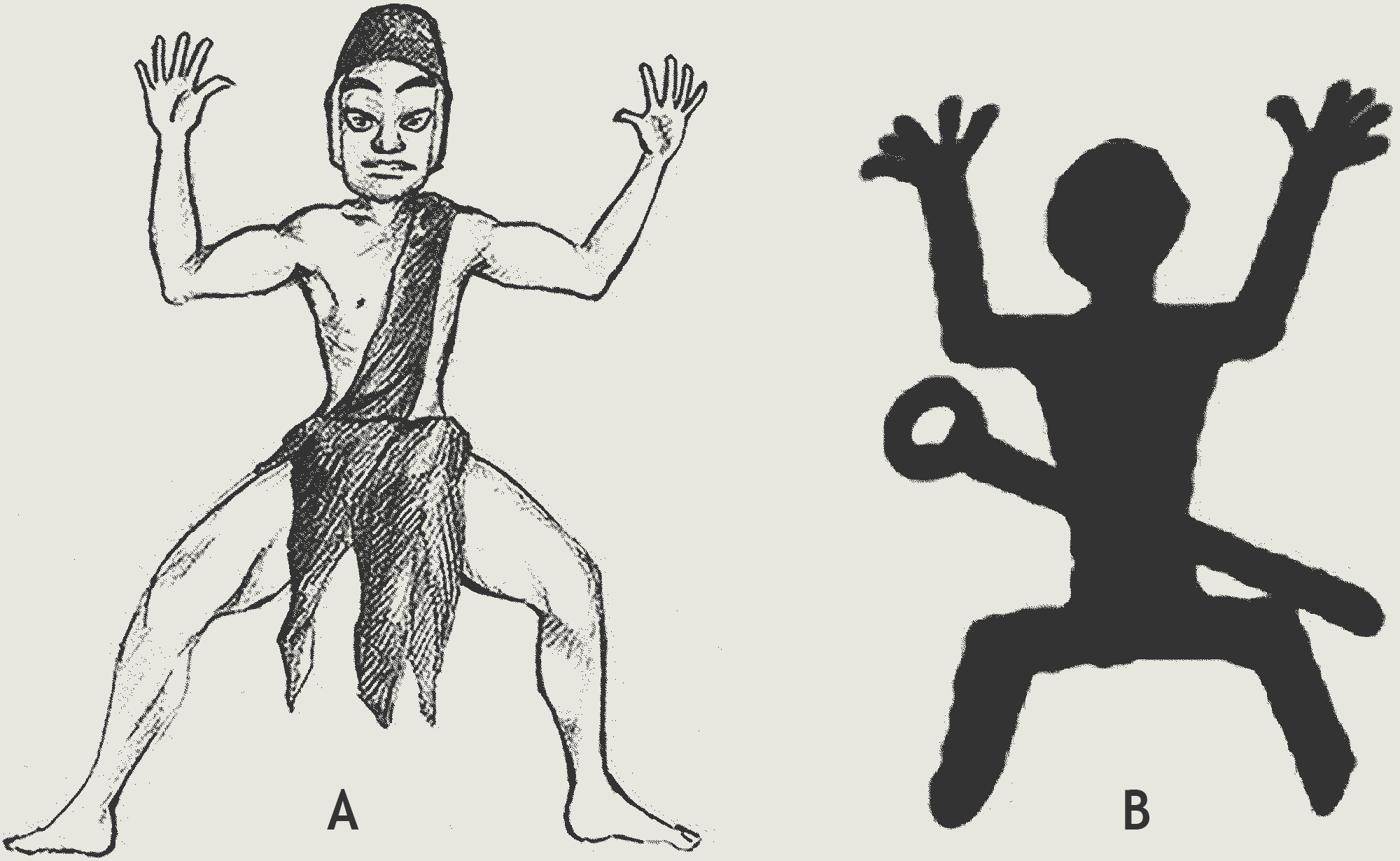

According to some scholars, the Huashan rock art site was created to worship the mighty thunder god (e.g. Yu 2004: 164). The thunder god is not directly depicted by the images but the main reason for this interpretation lies in the uniform posture of the ‘human’ motifs. The anthropomorphs, either in frontal view or in profile, are all painted in the same posture, with arms bent up and legs semi-squatted. This posture is interpreted as ‘frog posture’ by most scholars (e.g. Liao 2002). Frogs are closely related to the thunder god in the Zhuang ethnic religious beliefs. They are perceived as sons and daughters of the thunder god and messengers between heaven and earth (Jiang 1991: 12). Even today, the local ethnic groups still practise rituals and ceremonies in which they imitate frog postures in dancing to entreat the thunder god for favourable weather, such as a widespread ritual named ‘xingma dance’, performed by local wizards called shigong (Liao 2002: 363) (Fig. 4).

Because the painted ‘human’ motifs strikingly resemble the so-called ‘frog dance’, it is possible that the paintings represented a grand ritual in which people danced with a frog posture to worship the thunder god (Liao 2002: 82).

The ethnographic sources

In subtropical regions, floods and droughts, both related to water, alternatively affect agricultural production. Like thunder, water also plays a crucial role in the Zhuang culture. However, unlike the thunder god Duzbyaj, the water god Duzngieg has been viewed as evil. In the Zhuang mythology, Duzngieg is the largest water monster, responsible for causing floods and droughts. Scholars interpret Duzngieg as a water snake, a rhinoceros or a crocodile (Qiu 1996: 298; Luo 2006: 173; Liao 2002: 194). According to historical records written in the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), the Luo Yue people tattooed their bodies with patterns of water predators as a way to deter them (Chapuis 1995: 7). Today, the Zhuang people’s cult of the water god is mainly represented in two types of rituals: ‘land sacrifice’ and ‘water sacrifice’. The former refers to rituals held in the temples devoted to the water god, while the latter applies to rituals performed on the rivers. In ‘water sacrifice’, people wearing special costumes paddle the wooden boats, whose prows and sterns have been sculptured into the shape of a dragon or water bird, beat drums and gongs, and throw offerings into the water, as a way to please the water god (Qiu 1996: 299).

In the Zhuang mythology, water also represents the underworld. There have been many funerary rituals with water playing an important role among different Zhuang groups (Liao 2002: 195). For example, in some groups, when someone dies, before the funeral their family will carry the person’s clothes to the riverside, and pray for the water god to guide the dead in the underworld (Liao 2002: 182). If we take a look beyond the Sino-Vietnamese border, something that has not been traditionally done by Chinese scholarship, there is more evidence concerning the relationship between water and funerary rituals. On the Red River Plain, the Luo Yue (called ‘Lac Viet’ in Vietnamese) created a magnificent bronze culture between about 700 BCE and 100 CE, named Dong-son culture. Some scholars have studied the decorations on the Dong-son drums to explore the rituals of the Luo Yue people (e.g. Higham 1996: 124). Dong-son drums are characterised by the motifs of flying herons and plumed people in boats. According to Victor Golubew, the motifs symbolised the golden boat carrying the soul of the dead to the Island of Paradise which rose in the middle of the Ocean of Clouds (Golubew 1929: 38). Charles Higham (1996: 133) also stated that the ‘boat scenes’ decorated on bronze drums excavated in Vietnam probably represent funeral rites, in which context the herons would symbolise longevity and the boats may be carrying away the dead spirit. Moreover, some Vietnamese today still carry their dead to eternity over the oceans on ‘Bat Nha’ junks, a type of sailing boats (Chapuis 1995: 8). In fact, not just in the Dong-son culture, bronze drums have been found in abundance in south-western China, and they are the most representative implements of many non-Han ethnic cultures in this area. The function of the drums, often found in burials, remains debatable: according to historical records, they have been used in warfare, funerary and other ceremonial rites (Heidhues 2000: 19). According to the historical text Hou Han Shu (History of the Eastern Han), Ma Yuan (14 BCE – 49 CE), the Chinese general who subdued a Vietnamese uprising in 40–43 CE, confiscated and destroyed the bronze drums of the Luo Yue chieftains who were his adversaries (Tan 1987: 587), attesting to the drums’ significance in the local culture. Bronze drums were normally richly decorated, usually with a starburst pattern in the centre of the tympanum, and surrounded with geometric patterns, ‘scenes’ of ‘daily life’ and ‘war’, ‘animals’, ‘birds’ and ‘boats’. Even though the ‘scene’ of boats carrying plumed people is a common theme decorated on many types of bronze drums, the Shizhaishan type (called Dong-son type in Vietnam) has the most similar ‘scenes’ in the decorations compared to those of the Huashan rock art site. Shizhaishan type bronze drums were widely excavated in southwestern China and Southeast Asia. According to the Chinese scholars, they were popular between 600 BCE – 100 CE, as indicated by 14C dating (Wang 1990: 540). Vietnamese scholars claimed an earlier beginning of 700 BCE (Nyuyen 1974: 101).

Vietnamese scholars also argue that it is possible that the Luo Yue people were the ancestors of the Dayak people (e.g. Dao 1976: 132). The Dayaks of Kalimantan and other parts of Borneo in Southeast Asia have the tradition of sending their dead to the ocean on a type of boat. Their funeral ritual resembles the boat motifs on the Dong-son drums. They believe that the boats, which now carry the dead away, once carried their ancestors from somewhere else to the island (Dao 1976: 132).

Water in the Huashan rock art site

The Huashan rock art site has been closely related to the water god because of its ‘boat scenes’. The ‘boat scenes’ depicted on the Huashan rock art panel resemble the rituals devoted to the water god as practised by the Zhuang people today (Qiu 1996: 299). I would argue that they also resemble the ‘boat scenes’ cast on many bronze objects from the Dong-son culture, such as bronze drums and vessels (see Higham 1996 for a study of these drums) (Fig. 5). There is no way to be certain whether the ‘boat scenes’ of the Huashan rock art panel represented similar rituals in antiquity, but it is reasonable to assume that the water cult played an important role in the ancient Luo Yue spiritual practices. Furthermore, a large number of circle motifs were painted on the Huashan rock art panel, interpreted by most scholars as bronze drums (Qin et al. 1987: 167). Among the Zhuang people, there are folklores about bronze drums flying out during nights to fight with Duzngieg, the water god who brings floods and droughts to the earth (Luo 2006: 175). So it is possible to argue here that the depictions of bronze drums in the Huashan rock art site represent the Luo Yue people’s yearning for a world without natural disasters.

The ethnographic sources

In Zhuang mythology, the middle part of the world ‘earth’, where human beings live, also has a representative god, Baeuqloegdoz, the god of ancestors. However, the worship of Baeuqloegdoz is more closely related to the religious practice of ancestor worship than to that of animism, since Baeuqloegdoz is viewed by the Zhuang people as their first ancestor (Liang and Liao 2005: 1). According to legends, Baeuqloegdoz defeated his two brothers, the thunder god Duzbyaj and the water god Duzngieg, and created human beings with the goddess Mehmyok, who has become the flower goddess representing fertility and childbirth (Liao 2002: 118). Baeuqloegdoz has been greatly respected by the Zhuang people. For example, in rituals, if the local wizards, the shigong, need to ask for help from the gods, they must ask Baeuqloegdoz first, and then also the other gods (Yu 2004: 32). Except for the worship of Baeuqloegdoz, general ancestor worship has been pervasive in the Zhuang region. In festivals, rituals devoted to ancestors could be seen almost everywhere (Liao 2002: 176).

Earth in the Huashan rock art site

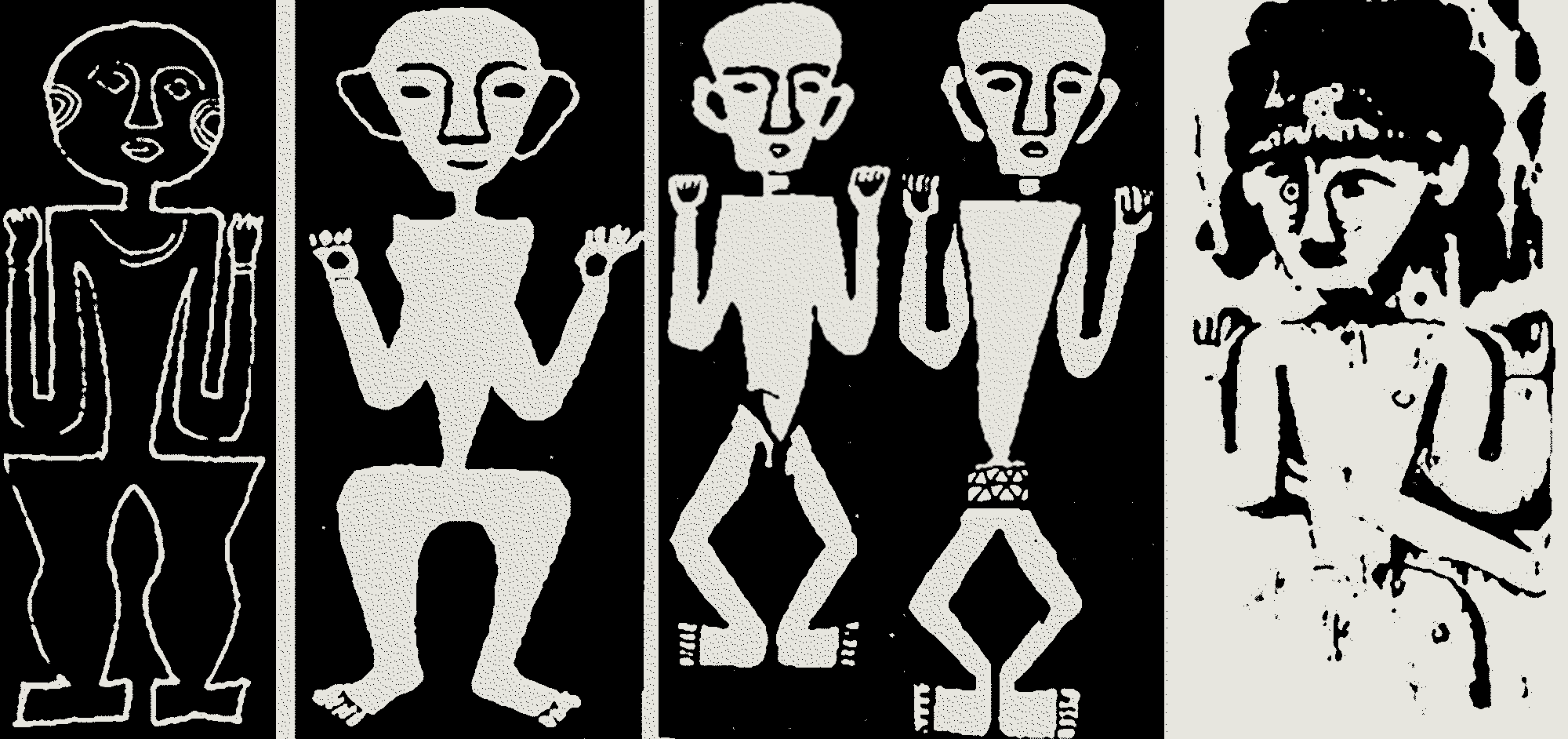

Another interpretation of the Huashan rock art site argues that it represents the ancestor worship of the Luo Yue people (Qin et al. 1987: 175). For example, the dominant human figures of each ‘scene’ could be interpreted as the depictions of great leaders in Luo Yue people’s memory. Today, many Zhuang people still believe that people’s souls exist after the body perishes, and the souls of ancestors would protect the descendants if worshipped properly (Liao 2002: 27). Some Zhuang groups still deify their renowned ancestors to be the local guardian gods or goddesses (Liao 2002: 32). According to some Vietnamese scholars, similar beliefs could be commonly found among the Muong people of Vietnam (Dao 1976: 235). Moreover, the ethnic minority Gaoshan people in Taiwan, whose ancestors are believed to have had close relations with the Luo Yue people, still have the tradition of carving their ancestors’ images on wooden boards and paying homage to the carved boards. Those images all have the same posture, with arms bent up and legs apart, sometimes with a sword hanging at waist, resembling the ‘human’ motifs of Huashan rock art (Qin et al. 1987: 176) (Fig. 6). Considering the essential connection between ancestor and the earth in the Zhuang people’s cosmology, it is highly possible that the ancestor worship presumably depicted in the Huashan rock art could be viewed as a spiritual practice devoted to the great earth.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ The Huashan Rock Art Site

→ Sacred Meeting Place for Sky, Water and Earth

→ Introduction to the Huashan Rock Art Site

→ UNESCO World Heritage Site

→ Huashan Rock Art Gallery

→ Huashan Local Ethnic Culture

→ Huashan Historical Background

→ Religious Beliefs of the Luo Yue

→ Cosmology of Huashan Rock Art

→ 38 Huashan Rock Art Sites

→ Protection of Zuojiang Huashan

→ Wushan Rock Art

→ China Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network