by Paul Taçon

ARC Australian Laureate Fellow (2016-2021).

Chair in Rock Art Research and Professor of Anthropology and Archaeology, Griffith University, Australia.

Director, The Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit (PERAHU)

Rock art tourism is a global phenomenon that began over 100 years ago in Europe and has steadily accelerated since the 1950s in many parts of the world. Today it occurs in most countries with rock art and in some places, such as parts of France (Duval et al. 2018) or China (Gao 2017), rock art tourism has been heavily invested in. Not only are actual rock art sites receiving much tourist attention but also rock art museums and rock art replicas, such as those of Chauvet, Lascaux (now up to replica 3) and Altamira in France and Spain which attract hundreds of thousands of visitors each year (Duval et al. 2018, 2019). But as Duval et al. (2018:1037) note: ‘Rock art tourism raises many questions: Why rock art tourism? Who does it aim to attract? Who does it benefit, and how? How will developments at rock art sites help secure and enhance the heritage values of those sites? Who should have a say in developments? Whose views are most important, and why?’

Duval et al. (2018:1021) also argue: “Most World Heritage Sites that feature rock art, such as Altamira (Spain), Côa Valley (Portugal), Valcamonica (Italy), Tsodilo (Botswana), the Maloti-Drakensberg (South Africa), Twyfelfontein (Namibia), Kakadu (Australia), Gobustan (Azerbaijan), and Serra da Capivara (Brazil), require considerable specialized tourism planning and infrastructure”. However, as Sullivan (1995) notes infrastructure can also create problems. For instance, “Use of boardwalks at once protects the sites and concentrates visitors into a defined area; it can also make crowding and congestion worse” (1995:84).

Aboriginal Australians maintain powerful connections to rock art sites and argue these heritage places are a part of living culture (Taçon 2019; Williams et al. 2019). Moreover, most Indigenous Australians desire to share their heritage with the wider world and over 100 rock art sites are open for guided or unescorted visitation. But infrastructure and resources vary widely and rarely do sites have conservation and/or management plans.

A sense of both natural and cultural history can be experienced when visiting rock art sites and often personal well-being is enhanced for both individuals from communities associated with rock art sites and outside visitors (Taçon 2019; Taçon and Baker 2019). But the opposite is also true in that damage to rock art sites can severely harm the well-being of people associated with the sites, especially that of Indigenous people.

Here I report briefly on what occurred at a significant rock art site called Baloon Cave once accessible for public visitation until it was severely damaged by fire in late 2018 in order to alert the worldwide community to both the physical and spiritual devastation inappropriate materials used for infrastructure can have when something goes wrong.

Baloon Cave is located in Carnarvon Gorge, central Queensland, Australia. It was one of four rock art sites open to the public for visitation in Carnarvon Gorge and the closest to the visitor area and ranger station. It is known for its sets of stencilled hands and a series of hafted stone axe stencils. Initially access to Baloon Cave was via a stone and soil walking track, with low handrails separating visitors from the art panels. However, some vandalism occurred with lines and letters scratched over and into stencils.

To facilitate better access and to better protect the rock art a large viewing platform and walkway was installed at Baloon Cave in 2014 (Figure 1 and see https://www.wagner.com.au/main/our-projects/baloon-cave-viewing-platform for photos immediately after installation). REPLAS Enduroplank recycled plastic products (see http://www.replas.com.au/tag/balloon-cave/) were used with composite fibre structural components. On the REPLAS website the Enduroplank is promoted as a low maintenance endurable material suitable for Baloon Cave (http://www.replas.com.au/carnarvon-national-park-upgraded-replas-enduroplank-viewing-platform/):

- The perfect fit-for-purpose as a low maintenance, long lasting product lies Replas Enduroplank™, an upgrade for the pathway near this cave. This recycled plastic decking solution gives better access to the National Park’s guests.

- Not only is this recycled product low maintenance and long lasting, it is durable enough to handle to walkers, hikers, and even 4WD vehicles to head right into the heart of this country!

It also is promoted as fire retardant but fire testing undertaken in December 2017 appears to have limited mixed results (see Abraham 2018, available on the REPLAS website).

Recycled plastic had been used for a rock art viewing platform at Nganalang, Keep River National Park, Northern Territory. It too was said to be fire retardant but in 2008:

- once the plastic material ignited, the severe heat generated caused the painted rock surface to shatter and disintegrate, falling to the floor of the shelter. The follow up conservation action in consultation with Traditional Owners was confined essentially to a clean up, placing the shattered material near the entrance of the shelter and to initiate baseline monitoring to assess the need for any future intervention (Lambert and Welsh 2011:47).

In December 2018, the Baloon Cave viewing platform and walkway was burnt to the ground. At both Nganalang, Keep River and Baloon Cave, Carnarvon it appears a hot fire melted and then ignited part of the infrastructure, resulting in an extremely hot explosive fire with heat so intense that massive exfoliation of nearby rock surfaces resulted, destroying or severely damaging rock art in the process, as well as coating areas with soot.

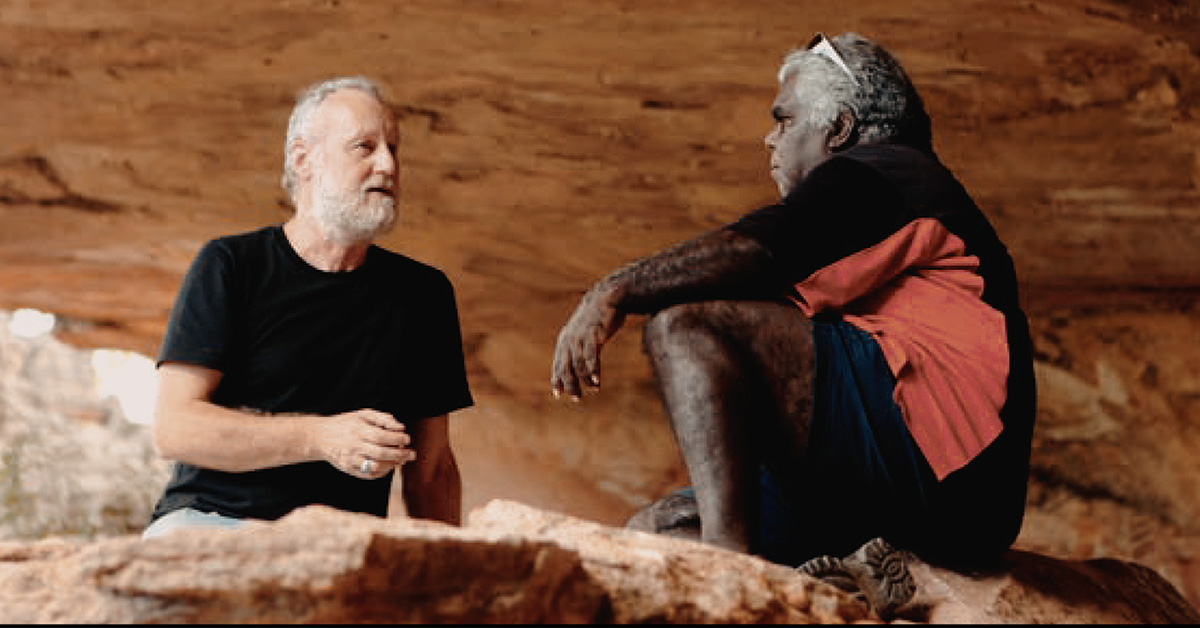

In early January 2019, soon after the fire, I inspected the walkway infrastructure leading up to Baloon Cave, including the remains of both recycled plastic and wooden walking tracks and bridges, with five Bidjara and Garingbal Aboriginal community members. One of our first observations was that the recycled plastic infrastructure was badly burnt and melted but much of the wooden infrastructure, although blackened, was largely intact. The fire was particularly devastating where the viewing platform and walkways leading up to it once stood. This infrastructure was completely destroyed, severely damaging the rock shelter and art in the process (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). The heat must have been very intense as much of the rock shelter surface exfoliated and collapsed. Black soot covered remaining parts of the shelter wall and ceiling.

Rock art at the site was heavily impacted. Damage to the main panel consists of exfoliation to the left, right and above right; cracking at the upper right; and a coating of soot over most of the stencilled hands and all of the hafted axe stencils (Figure 5 and Figure 6). As one approaches the panel, at first it appears it is completely blackened but closer inspection and photography with the light at the right angle reveals the stencils underneath.

Damage to the rare hafted stone axe stencils is pronounced as not only have they been blackened but also where two of them are located the rock has both cracked and exfoliated. The cracked portion at the left looks as if it could easily collapse. It may be possible to remove the soot and to consolidate the panel but this needs further investigation and assessment. Some soot has washed away in recent heavy rain. There is a risk that the rock above the major new crack could sheer off and fall to the ground, taking portions of the stencils with it.

If it be decided to attempt a repair of the panel it should be undertaken cautiously, so as to not create new damage. More generally, physical intervention at rock art sites should always be a last resort, carefully considered and undertaken only by knowledgeable/experienced professionals.

The fire damage to Baloon Cave and its rock art devastated the local Aboriginal community associated with it. Some people were physically ill for up to a week afterward. Emotions ran high for many months after the fire and many people felt spiritually demoralised for some time.

Of course, the main conclusion from what occurred at Baloon Cave is that recycled plastic products should never be used again at rock art sites, especially for walkways and viewing platforms. However, wooden infrastructure is also problematic and there have been many instances where wooden platforms and/or walkways caught fire and then caused damage to rock art panels in Australia, South Africa and elsewhere. As Lambert and Welsh (2011:48) conclude: “Clearly, new boardwalks should no longer be constructed using combustible material, and old wooden boardwalks need to eventually be replaced with a non-combustible material or design”. Metal walkways and viewing platforms, although more expensive, might be the way forward for some sites. One of the best examples was installed at the Jibbon rock art site on the edge of Royal National Park, New South Wales (Figure 7 and see Williams et al. 2019).

The Aboriginal people associated with Baloon Cave have been extremely upset about what occurred but have been working toward healing by way of positive outcomes. These include warning others not to use recycled plastic or any material at a rock art site that could put the art at risk, new relationships to better look after cultural heritage, finding a new purpose for Baloon Cave, and establishing a Rock Art Protection Strategy.

Fred Conway, Dale Harding, Milton Lawton, Will Lawton and Darren McCleod are thanked for taking me to Baloon Cave, assistance with writing a report on the fire damage and permission to both distribute the report and to post this article. The wider Bijara-Garingbal community is also thanked. This research was supported by an Australian Research Council Australian Laureate Fellowship (FL160100123) and Griffith University.

Duval, M., Gauchon, C. and Smith, B., 2018, Rock art Tourism. In Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art, edited by B. David and I. McNiven (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp.1021-1041.

Duval, M., Smith, B., Gauchon, C., Mayer, L. and Malgat, C., 2019, "I have visited the Chauvet Cave": the heritage experience of a rock art replica. International Journal of Heritage Studies. doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1620832

Gao, Q., 2017, Social values and rock art tourism: an ethnographic study of the Huashan rock art area (China). Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 19(1), 82-95.

Lambert, D. and B. Welsh. 2011. Fire and rock art. Rock Art Research 28(1):45-48.

Sullivan, H., 1995, Visitor management at painting sites in Kakadu National Park. In Management of Rock Art Imagery, edited by G.K. Ward and L.A. Ward. Occasional AURA Publication 9 (Melbourne: Archaeological Publications), pp.82-87.

Taçon, P.S.C., 2019, Connecting to the Ancestors: why rock art is important for Indigenous Australians and their well-being. Rock Art Research 36(1), 5-14.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation