Quoting from the text of the lecture on the Statues, he says, "at some unidentified date prior to AD 380, the first settlers landed on Easter Island, and found a verdant island covered by trees, shrubs, and palms." He proved this to be true from the extensive pollen samples taken from the crater lakes with the aid of 26 feet long cores from the sediments.

His excavations proved that there were 3 separate epochs in the History of Easter Island, which the archaeologists have named Early, Middle and Late Periods. In the Early Period there was no production of giant statues, only altar-like elevations of very large, and most precisely cut and joined stones, which were erected with their facades towards the ocean, and a sunken court on the inland side. They were astronomically oriented, and constructed by highly specialised stone masons who studied the annual movement of the sun and in their religious architecture.

Period was initiated by the sudden end of all work in Rano Raraku quarries. During this period the Statues were one by one overthrow, and everywhere are evidence of warfare and destruction. When the first Europeans settled ashore and became able to communicate directly with the Easter Islanders, they were told of two different arrivals, one from the East and one from the West. They consistently stressed that after a period of peaceful coexistence, their forefathers had almost exterminated the original people, thus leaving the present Polynesian population as sole inhabitants of Easter Island.

Thor Heyerdahl and his colleagues collected a great deal of evidence concerning the Early Period. Aquatic plants and the building of reed-boats, the use of double blade paddles, one-piece stone fish hooks, the shape of the dwellings, stone pounders, and needles, all point to the East and are not found in the West.

Lastly the existence of the rongo-rongo tablets. The Easter Island script was incised on wooden tablets, the only other place that this type of script has been found is among the early Indians who lived around Lake Titicaca high in the Andes. There is no evidence that the Polynesian people ever had the ability to write or invent a script, leaving the question of "How did they get there?".

Cocos Island, south-west of Costa Rica, lies 300 miles out into the Pacific. It was so named by the Spaniards because there was an abundance of Coconut trees growing on it in great Groves.

One of the first visitors was Captain Wafer who called at the Island in 1685. He also reported that Groves of Coconuts covered the island. In 1956 when Thor Heyerdahl visited Cocos Island he found nothing but dense virgin jungle, and that all the coconuts had disappeared.

The Coconut Palm, cocos nucifera, first became known to the Europeans when they discovered India and Indonesia, long before the discovery of America, however it is now generally believed that the Coconut originated in America. To quote the botanist O.F.Cook [1910], "if the Coconut could be submitted as a new natural object to a specialist familiar with all other known palms, he would without hesitation recognise it as a product of America, since all the score of related genera, including about 300 species, are American. With equal confidence the specialist would assign the Coconut to South America, because all other species of the genus Cocos are confined to that continent. He would further locate it in the north-western portion of South America, because the wild species of Cocos of that region are much more similar to the Coconut than are those of the Amazon Valley and eastern Brazil."

The uses of the Coconut have been most highly developed in the Pacific Islands because the lack of other plants has compelled the inhabitants to depend on it more and more, but the plant itself had to be brought from the only part of the world where such palms grew, South America.

The presence all the large numbers of Coconuts on Cocos Island in the time of Wafer [1685] and their subsequent disappearance should be considered as evidence that the island was formerly inhabited, or its lease to regularly visited, by the maritime natives of the adjacent mainland. Even without a permanent population coconuts may have been planted and cared for by the natives of the mainland for use during fishing expeditions, a plan still followed in some localities in the Malay region.

Ethnologists may find in this hitherto unsuspecting primitive occupation of Cocos Island additional evidence of maritime skill of the Indians of the Pacific coast of tropical America, and be more willing to consider the possibility of prehistoric communications between the shores of the American continent and the Pacific Islands.

The idea that the Coconut Groves on Cocos Island were planted by man is substantially enforced by the fact that the island is bounded by high cliffs, apart from two small landing areas where streams run into the sea. There is simply no way that the coconuts could have been transported from the sea up the cliffs onto the plateau where the Spaniards discovered the groves, without the aid of Man.

The nearest possible Polynesian source from which coconuts could haveb een brought to Cocos Island is the Marquesas group. It would be reasonable to ask if there is any legendary memory within Polynesia as to the existence of any island east of the Marquesas. On the remarkably correct chart made for Captain Cook by Tupia of Ulitea, there is actually marked to the east of the Marquesas group an unidentified island named Utu [in English spelling Ootoo].

The natives of the Marquesas also independently told Captain Porter that there was an Island to the east of their group, known to them as Utupu [Ootoopoo]. He writes: "none of our navigators have yet discovered an island of that name, so situated; but in examining the chart of Tupia, we find nearly in the place marked by the native of Nukuhiva and island called Ootoo. This chart, although not of the accuracy which would be expected from our hydrographers, was, nevertheless, constructed by Sir Joseph Banks, under the direction of Tupia, and was of the greatest assistance to Cook in discovering the island he had named."

What is remarkable, however, is that the only memory recorded by Porter as associated with the easterly island was that this was the place from which the early Marquesans had originally obtained the coconut.

It is the opinion of Thor Heyerdahl that the extensive coconut groves on the Cocos Island would be of little use to anyone unless we assume that the island was either densely inhabited or else favourably located for voyagers who frequented the area and were in need of convenient supplies. He states that from his personal experience he could testify that no natural product was better suited as a provision for seafarers than newly picked, scarcely mature coconuts, which will withstand almost any amount of water spray and rough storage, and yet yield fresh liquid and substantial food for weeks during a voyage.

In recent years there has been an increasing tendency among archaeologists to explain the rapidly accumulating evidence of cultural contact between Guatemala, Ecuador, and Peru, as the result of direct ocean trade between the two areas. A glance at the map will show that Cocos Island is located directly on the sailing route between these countries.

The presence of pot shards on the Galapagos Islands, and aboriginal knowledge of centreboard navigation with sailing rafts in north-western South America, are strong arguments in favour of Cocos Island having been an important location as a port of call and supply station providing water and coconuts to the pre-Spanish navigators in the open ocean off Panama.

Aboriginal navigation in Peru and adjoining sections of north-western South America is a subject that is little known and still less understood by modern boat builders and anthropologist. The apparent reason is that the Peruvian Indian boat building was based on principles entirely different from those of our ancestry. To the European mind the only seaworthy vessel is one made buoyant by a watertight, air-filled hull, so big and high that it cannot be filled by the waves.

To the ancient Peruvians the only seaworthy craft was one which could never be filled by water because it's open construction formed no receptacle to retain the invading seas, which washed through. They achieved this by building exceedingly buoyant rafts of Balsa wood.

Sketch by F.E. Paris (1841) showing construction of a native balsa raft from the north-west coast of South America. The maximum length of raft is 80-90 feet, maximum width of a raft is 25-30 feet with a freight capacity of 20-25 tons.

His Pilot was sailing ahead to explore the coast southwards near the equator, when off northern Ecuador his ship suddenly met another sailing vessel of almost equal size, coming in the opposite direction.

The raft was manned by 20 Indian men and women, 11 of whom were thrown overboard, four were left with the raft, and two men and three women were retained by the Spanish to be trained as interpreters for later voyages. The Spaniards estimated the raft capacity at 36 tons, only a fraction less than their own vessel.

Their report stated that it carried masts and yards of very fine wood, and cotton sails in the same shape and manner as on their own ships. It had very good rigging of hemp, stronger than their own rope, and mooring stones for anchors. Many similar accounts described rafts made of long and light logs, always of odd number, 5,7,9 or 11, tied together with cross beams and covered by a deck. The larger ones had the ability to carry up to 50 men and three horses, and had a special cooking place on board in a thatched hut. The cargoes often included salt, another proof of their seaworthiness.

These rafts are navigated simply by raising and lowering centreboards inserted in the cracks between the logs. By raising and lowering these boards in different parts of the Balsa raft, the natives could perform on their raft all the manoeuvres of a regularly built and well rigged European vessel, and obtain speeds of 4 to 5 knots. Tiny models of the rafts have been found in graves, along with carved centreboards, near Arica in northern Chile. The sail was probably know on the Peruvian coast earlier than pottery and weaving.

During the last decades it has been an accepted premise among the New World anthropologist that North and South America have been successfully isolated from the rest of the world, but for a leakage across the Bering Straits. An ocean has pathways as alive as a river. The Japan Current loop through the North Pacific past Hawaii, travels down the coast of California and then back towards the Philippines above the equator. A portion of this current continues down the west coast Panama to Ecuador and Peru before travelling back towards Polynesia.

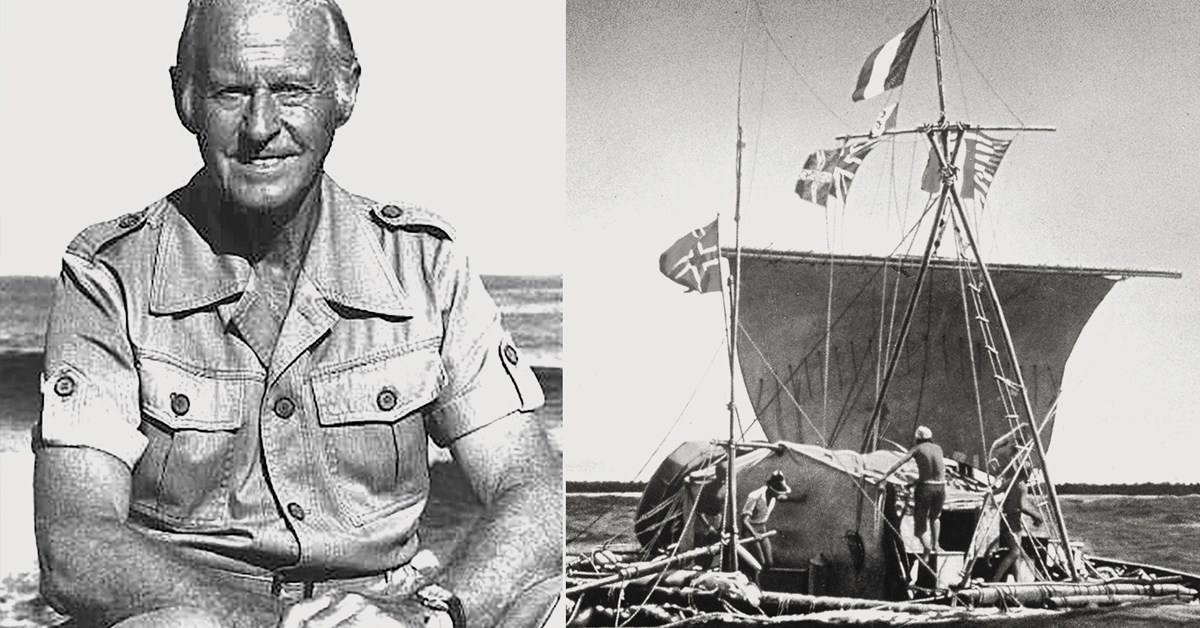

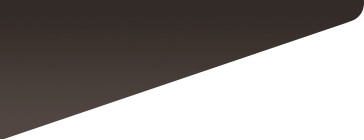

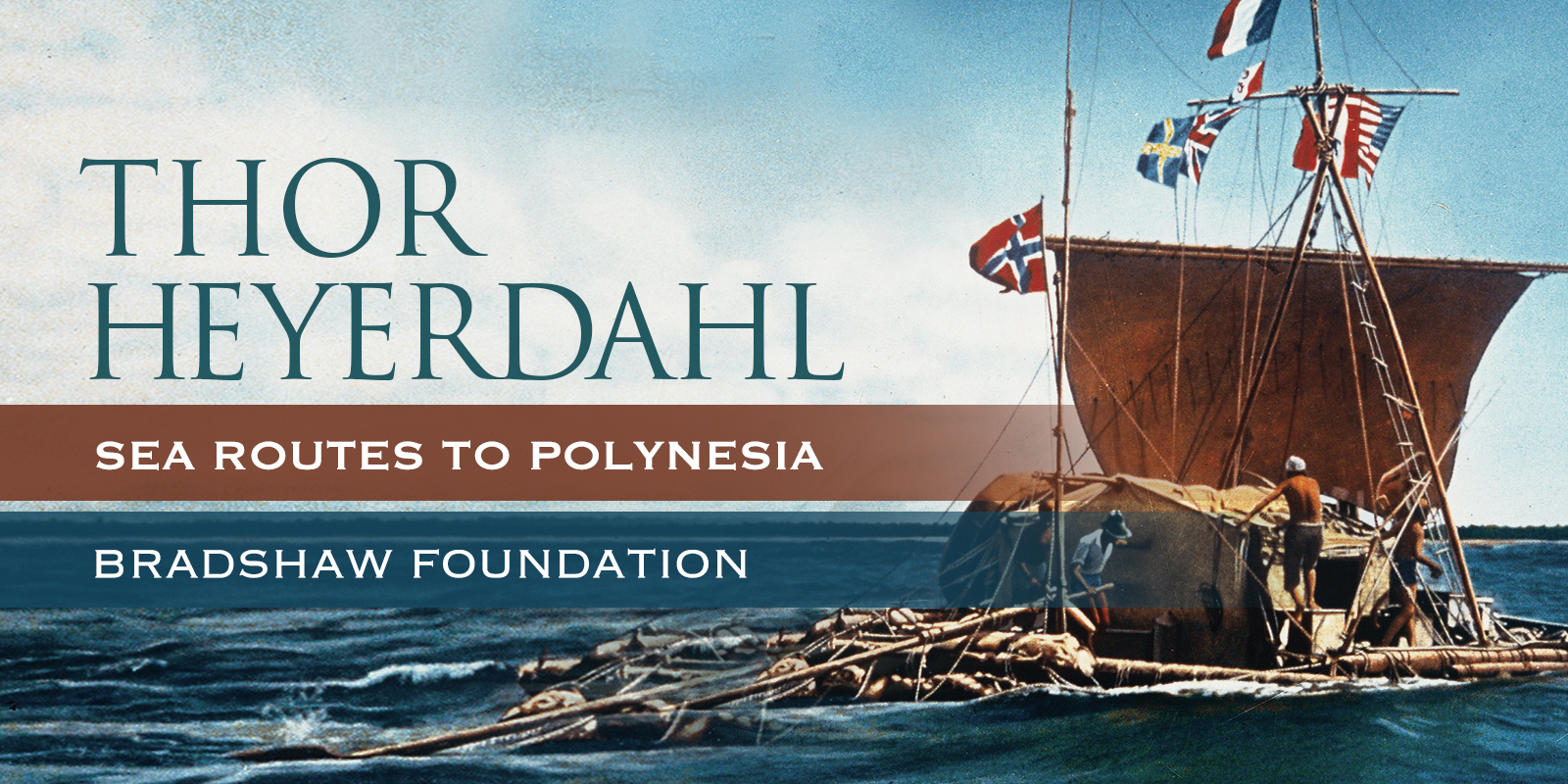

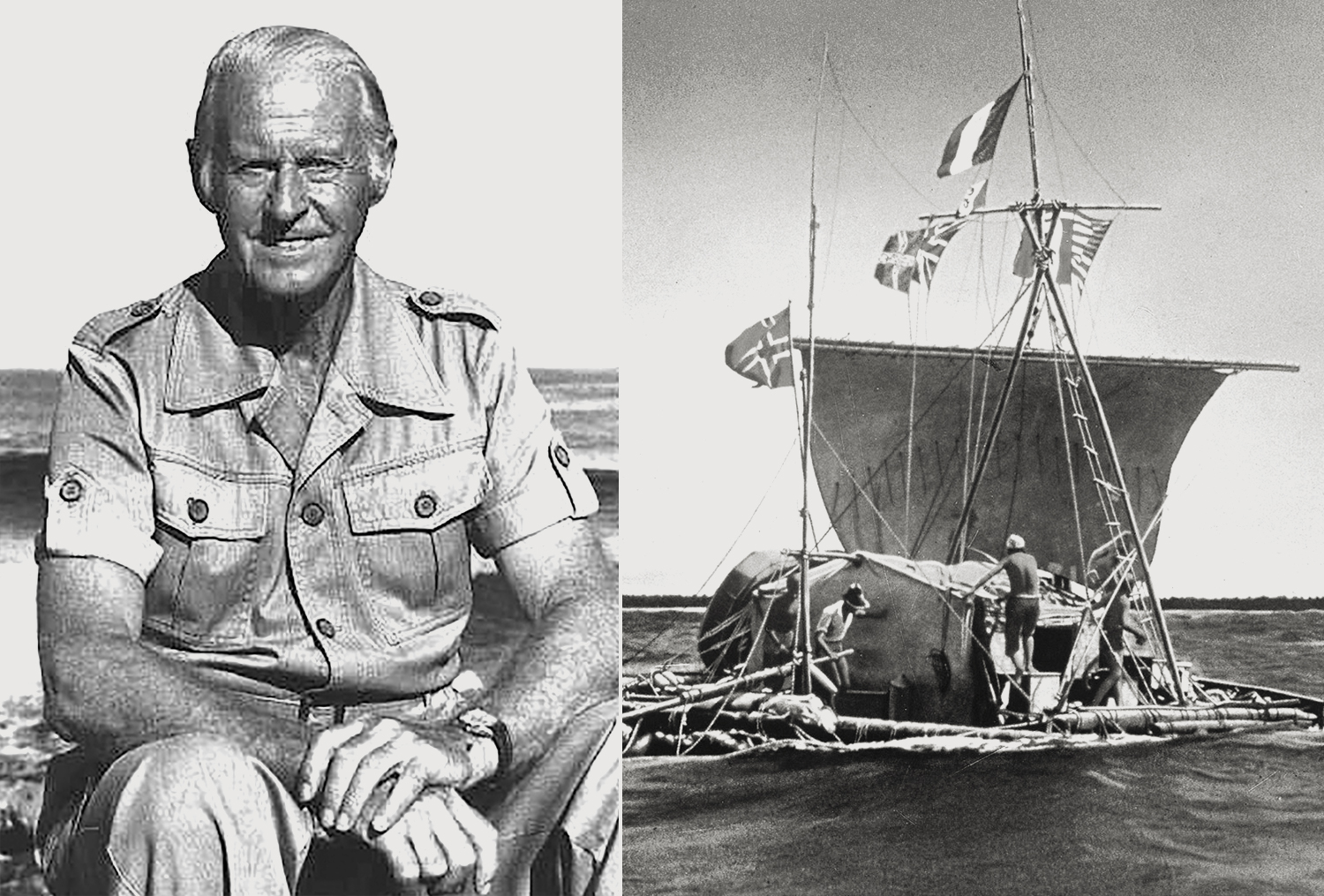

The great explorer and anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl used this southern current to sail the Kon Tiki raft on his 1947 epic voyage from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands. The dead distance between the point of departure and the point of arrival is approximately 4000 miles, and yet the raft only crossed 1000 miles of surface water. If another primitive craft had been able to travel with the same speed in an equally straight line, but in the opposite direction, it would have traversed about 7000 miles of surface water to reach Peru.

The reason is that the ocean surface itself was displaced about 3000 miles, or about 50 degrees of the Earth's circumference, during the time needed for the Kon Tiki crossing. Put another way it means that the Islands are located only about 1000 miles from Peru, whereas Peru is located 7000 miles from the Islands. The current travels at about 40 miles per 24 hours, and if the craft is sailing at 60 miles per 24 hours, it means that it would have travelled a 100 miles in one day, and the duration of the voyage would be 40 days. Travelling the opposite way at the same speed against the current it will only travel 20 miles per 24 hours and thus need 200 days to make the voyage. If the craft was only travelling 40 miles per 24 hours it would sail from Peru to the islands in 50 days, but at that speed going in the opposite direction it would never leave the islands.

In the Ship Museums of Oslo the Norwegians have on display some of the finest boats that you'll ever see, including three Viking ships of incomparable beauty. Also housed in one of the museums is the Kon Tiki, which, in its own way, is just as beautiful. Standing before this amazing vessel quite takes your breath away, and fills you with admiration for the great explorer and anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl. The raft is composed of 9 two-foot thick Balsa logs, ranging in length from 30 to 45 feet, the longest in the middle, lashed to cross beams, covered by a bamboo deck on which is an open hut. A bipod mast, carrying a square sail, five centreboards, and a steering-oar completed the construction.

The reason the Balsa logs did not chafe the rope lashings, was that the surface of logs became soft and spongy, and the ropes were left unharmed as if pressed between cork. The ropes proved to be tough enough to resist the assault of two storms with towering seas. The secret of the safety and seaworthiness of the unprotected Balsa raft, in spite of its negligible freeboard, was primarily its unique ability to rise with any threatening sea, thus riding over the dangerous water masses which would have broken aboard most other small craft.

Secondly it was the ingenious wash-through construction which allowed all water to disappear as through a sieve. Neither towering swells nor breaking wind-waves had any chance of getting a grip on the vessel, and the results was a feeling of complete security which no other open or small craft could have offered. Moreover the shallow construction of the raft, and the flexibility allowed by all the independent lashings, made it possible even to land directly on an exposure reef on the windward side of a dangerous archipelago.

During the ocean voyage a few experiments were carried out with the centreboards. It was found that the five centreboards, six feet deep and two feet wide, when securely attached, were enough to permit the raft to sail almost at right angles to the wind. It was also ascertained that by raising or lowering the centreboard fore or aft, the raft could be steered without using the steering oar. On this expedition an attempt to tack into the wind failed completely. In 1953 Thor Heyerdahl experimented on a smaller test raft constructed like the Kon Tiki of nine Balsa logs lashed together. He found that a correct interplay between the handling of the sail and the centreboards enabled him to tack against contrary wind, and even to sail back to the exact spot from where he had set off. The centreboard method of steering a raft was astonishing through its simplicity and effectiveness.

These experiments proved that the early Peruvian high cultures were very advanced in marine matters, and that an entire reappraisal of early Peruvian seamanship and navigation was necessary.

None of this is really surprising because in 1748 two Spanish naval officers became sufficiently intrigued by the navigation technique employed by the local Indians to look further into the history of the indigenous centreboards. Part of their report read as follows: -

"Hitherto we have only mentioned the construction and the uses they [the raft] are applied to, but the greatest singularity of the floating vessel is that it sails, tacks and works as well in contrary winds as ships with a keel, and makes very little leeway. This advantage it derives from another method of steering than by a rudder, namely, by some boards three or four yards in length, and half a yard in breadth, called guaras, which are placed vertically, both at the head and stern between the main beams. By thrusting some of these deep in the water, and raising others, they bear away, luff up, tack, lay to, and perform all the other motions of a regular ship. The method of steering by these centreboards is so simple, that once a Balsa is put in her proper course, one only has to raise or lower as occasions require, to keep the Balsa in her intended direction."

In 1852 Balsa rafts were observed visiting the Galapagos Islands, some 600 miles off the mainland coast.

Thor Heyerdahl through his brilliant experiments rediscovered the secret of how the Incas could sail their rafts into the wind, and like all the ingenious inventions the trick was exceedingly simple once it was learned. With sail and centreboard he was able to turn the raft all about and resume a new course into a contrary wind, thus proving for all practical reasons that there is no limits to the range of indigenous Peruvian water craft in the Pacific Ocean, and that no longer can we deny the likelihood that long voyages were undertaken by the coastal Peruvian population.

2012 Norway 118 mins PG-13

Directors: Joachim Rønning, Espen Sandberg

The story of legendary Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdal's epic 4,300 miles crossing of the Pacific on a balsa wood raft in 1947, in an effort prove it was possible for South Americans to settle in Polynesia in pre-Columbian times.

When the scientific community rejects his theory that South Americans were the first to settle in the Polynesian Islands, Heyerdahl resolves to prove its validity - and save his reputation - by embarking on the voyage himself. Recruiting a group of five men who are just bold enough to tackle the seemingly impossible trip, he builds a simple raft to original pre-Columbian specifications and sets off on the epic 101 day-long journey across the treacherous oceans to meet his fate, while the world watches.