SARAP will undertake this work through four components:

- Education and training in rock art site management.

- Building local capacity in specialist tourist guiding to rock art sites.

- Education and training for rock art interpretation and presentation for the public.

- Training in rock art site conservation interventions.

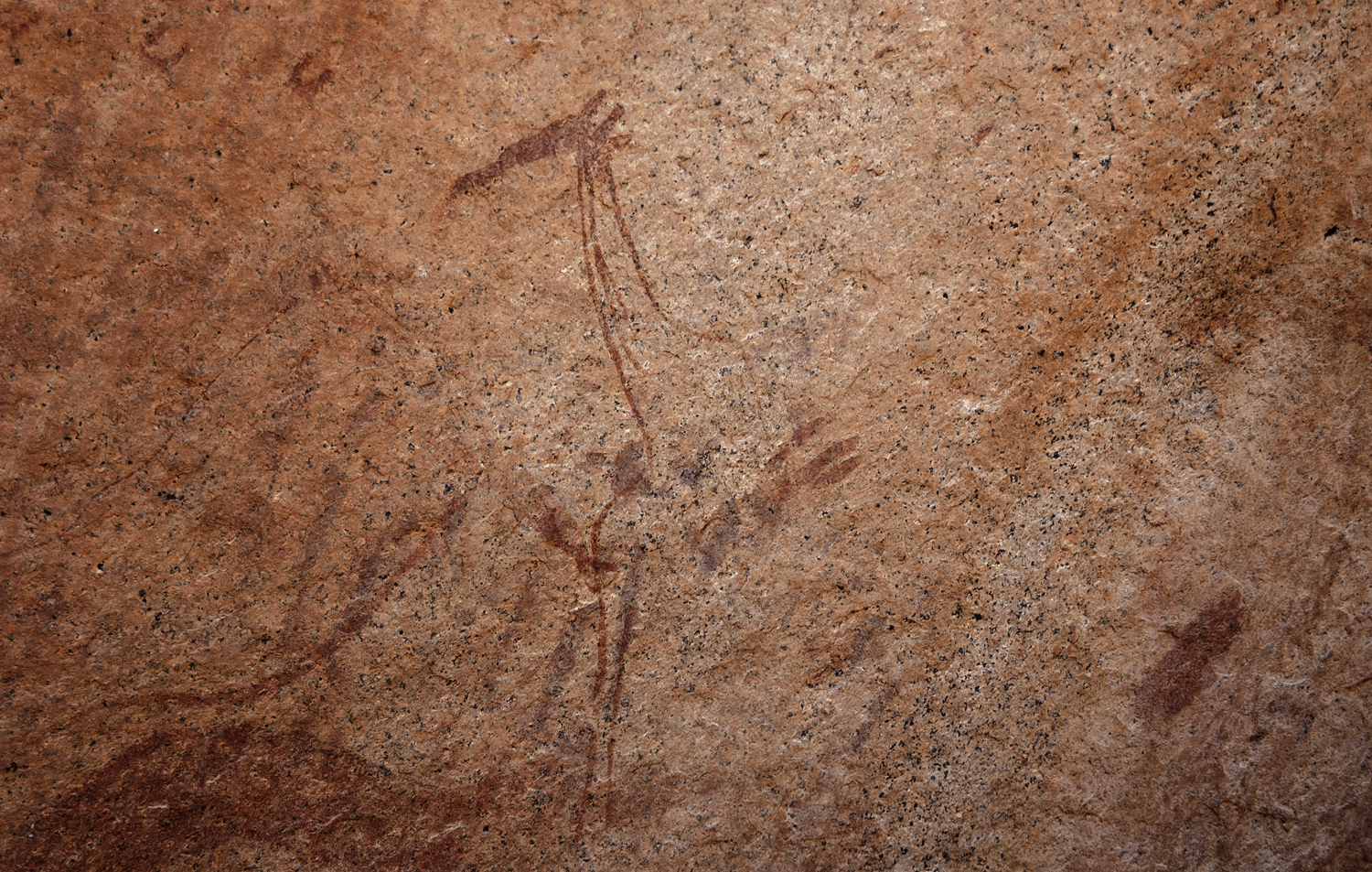

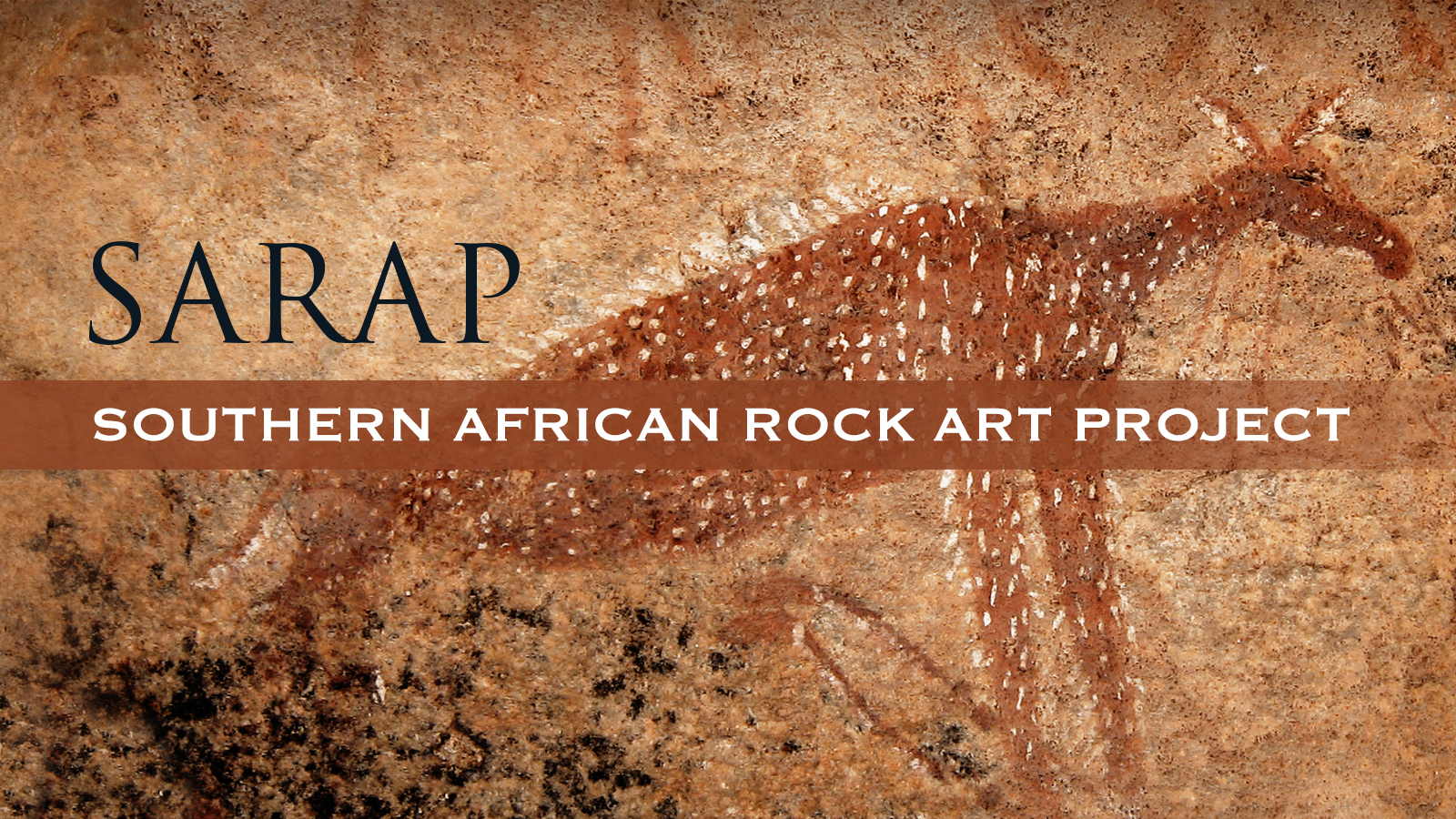

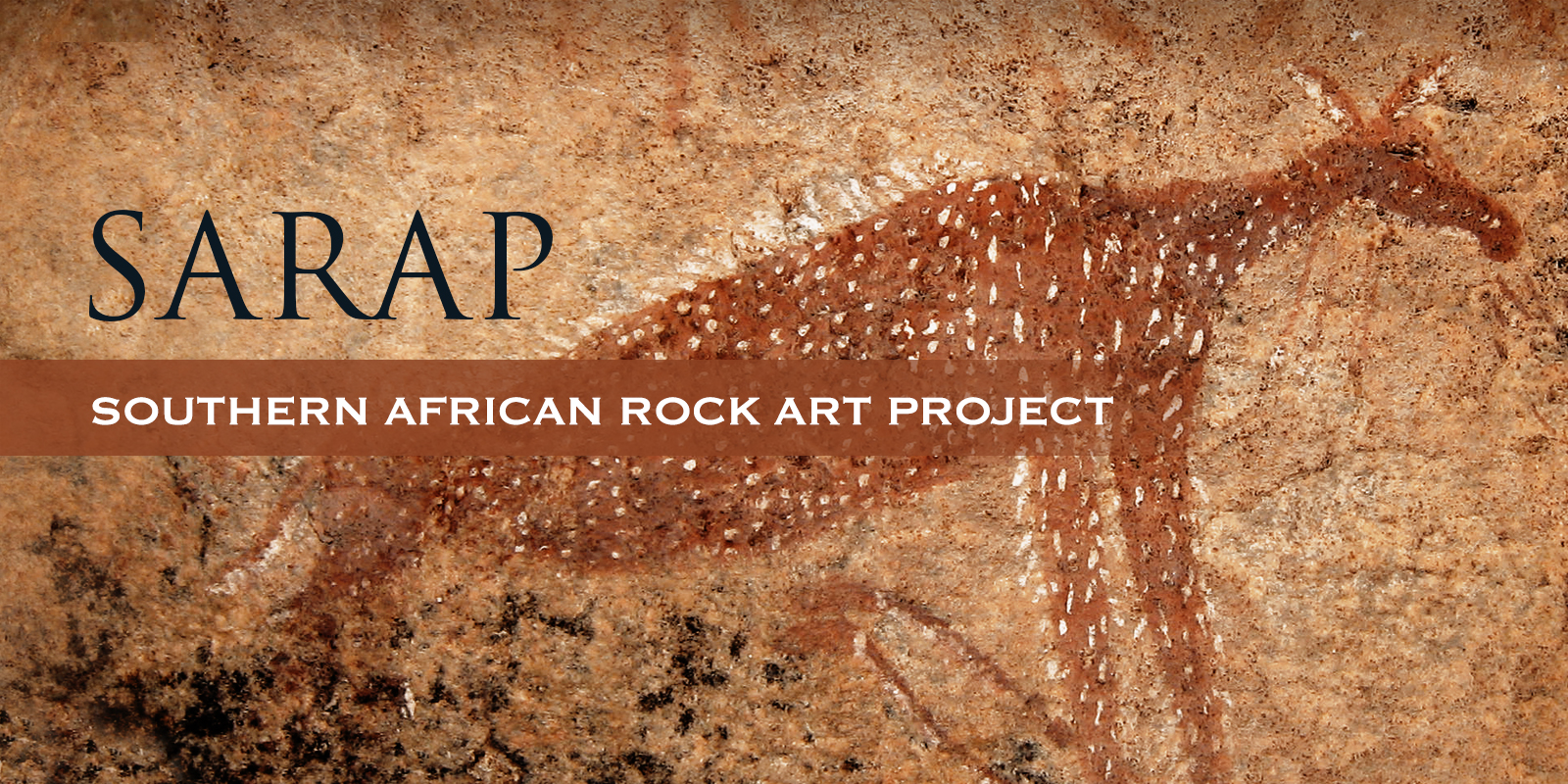

Rock art sites are a unique and lasting testament to the customs and beliefs of indigenous societies that have created them. Southern Africa contains one of the world's great repositories of rock art. In the region, rock paintings and engravings together record - over a period of nearly thirty millennia - the interactions of humans with one another and with their environment, and provide a significant depiction of their spiritual and ritual practices. Some of the rock art sites are considered creative masterpieces. There is an ethnographic record from the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly from the San people who created rock art in the region, and this record allows interpretation of some of the metaphors and symbols that are hundreds and even thousands of years old.

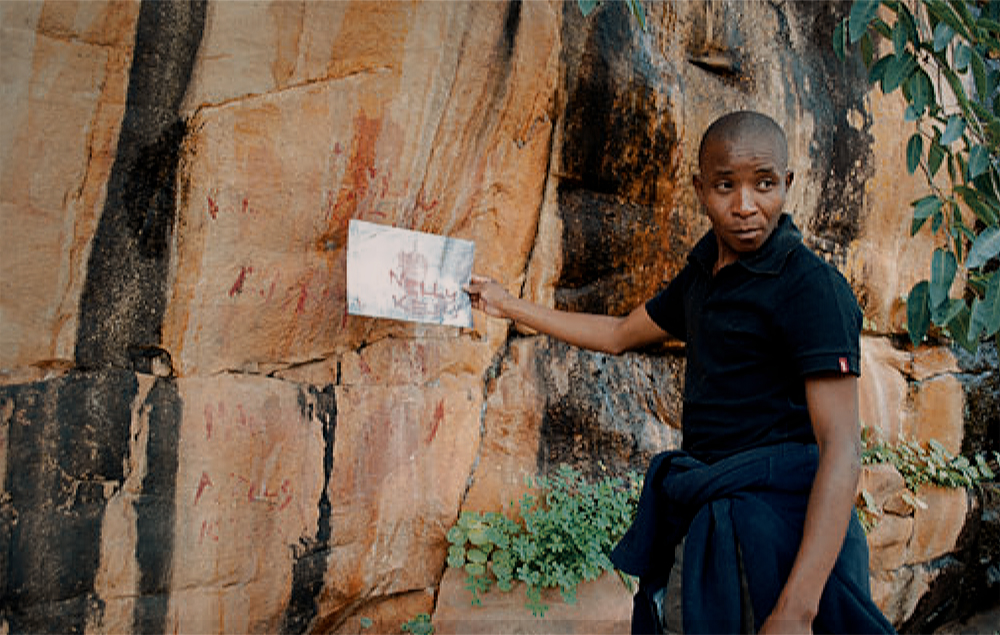

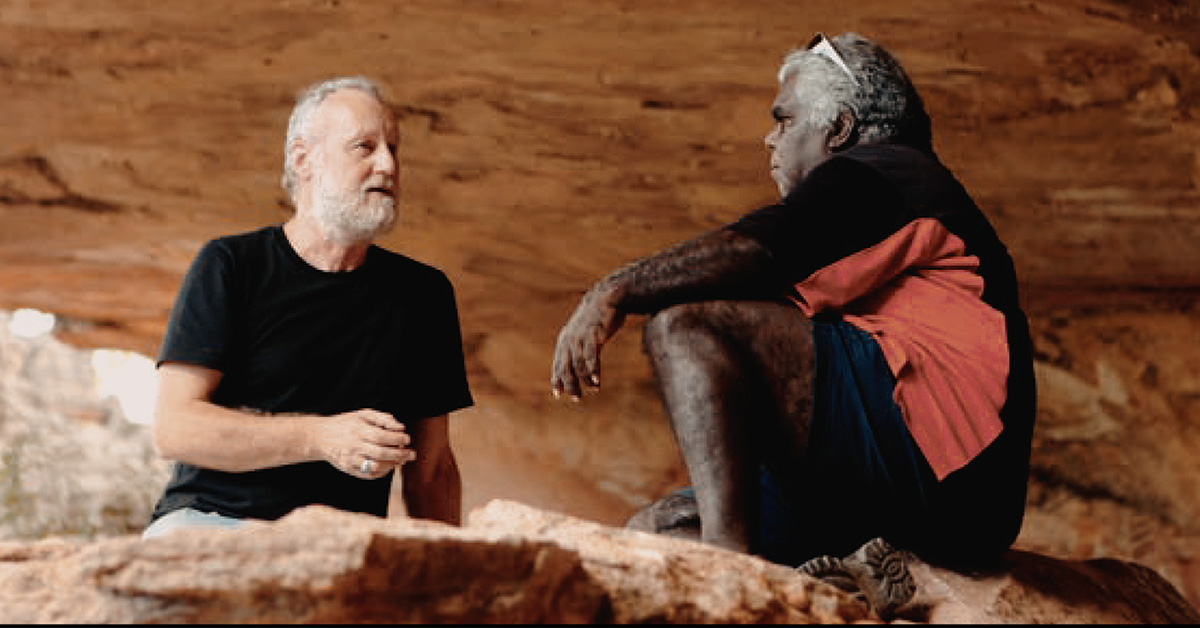

In the Southern African subcontinent, as in many places, rock art is endangered due to development and increased tourism, which at some sites has resulted in irreversible damage and loss. By empowering local communities as primary custodians, a group of stakeholders is formed with a vested interest in the protection of the sites. Such community-based approaches that teach protection, interpretation, and appropriate use are essential to sustainable management.

The Getty Conservation Institute has long recognized the universality of rock art as cultural heritage. Beginning in the late 1980s, the Institute offered short and long-term courses on rock art conservation, protection, and management. These included on-site training for persons responsible for the conservation and management of rock art sites. In 1987 the Institute conducted its first short-term course in rock art conservation. Held in Castellon, Spain, the course was designed to aid conservators in the field in the examination and documentation of rock art. In 1988 and 1989, the GCI organized workshops in rock art conservation and site management. The courses emphasized examination and documentation, identification of causes of deterioration, site interpretation, and site protection.

In 1988-1989, the GCI and the Canberra College of Advanced Education (now the University of Canberra) in Australia collaborated on a one-year graduate diploma course on rock art conservation. The course focused on understanding rock art as an element of material culture found around the world, methods of producing rock art, theory and practice of recording and conserving rock art, management requirements for rock art sites, and identifying and planning for applied research in the field of rock art conservation. The graduates of the program subsequently participated in a month-long GCI conservation project at the site of Painted Rock, a significant rock art site located in central California.

Growing out of the Institute's rock art conservation training activity was the GCI's field project on the Rock Art of Baja California, Mexico, conducted between 1994 and 1996. This project was a collaborative effort with the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), which focused on the management and protection of the remote rock art within the Baja California peninsula.

The Institute's past rock art efforts have been valuable in structuring its current involvement in rock art protection through the Southern African Rock Art Project (SARAP).

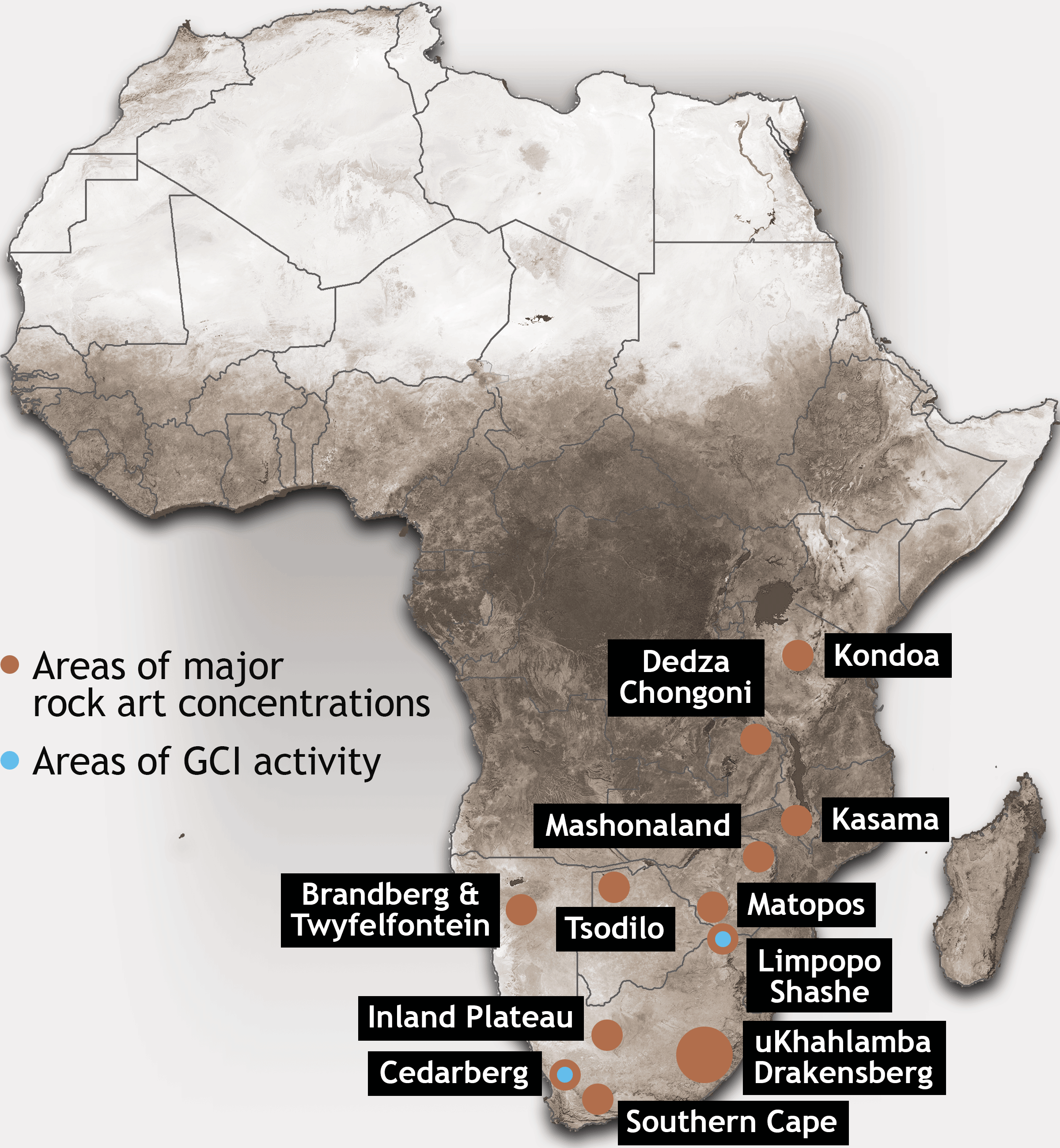

In 2003 the GCI commissioned a feasibility study to identify one or more areas rich in rock art in the Republic of South Africa where interpretation and management program, either for education or tourism, could be developed to serve as a model for sustainable conservation and community participation for similar sites in the Southern African subcontinent. Areas were assessed according to the following criteria. They should:

- Have several sites with either paintings or engravings that offer high quality rock art in reasonable quantity;

- Be situated in a local, provincial, or national park or nature reserve with stable management;

- Have an enthusiastic management structure prepared to offer quality assistance and commitment on a partnership basis;

- Include conservation problems that could provide challenges for research and development;

- Preferably be close to a community of Khoi-San descent interested in becoming involved in the site's protection and development;

- Be reasonably easy to incorporate into existing educational and/or tourism structures in the region; and

- Have enough challenges to warrant inviting rock art site managers from elsewhere in Southern Africa to participate in the development program, establish mutual contacts, and see the evolution of a viable project firsthand.

The two listed World Heritage Sites identified were Mapungubwe National Park on the southern bank of the Limpopo River, which forms the northern border of South Africa with Botswana and Zimbabwe; and the Cederberg Wilderness Area in the southwest of South Africa, a part of the Cape Floral Region World Heritage Site. Convinced of the value of the approach, the GCI initiated a collaborative effort with SARAP that also involved the South African National Parks (SANParks), the Rock Art Research Institute (RARI) at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, CapeNature (a provincial nature conservation authority), the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), and the Clanwilliam Living Landscape project based at the University of Cape Town.

A meeting of relevant stakeholders was held at the GCI in Los Angeles in August 2004 to establish short- and long-term objectives. Training, conservation, and stakeholder relationships were identified as the key issues to be addressed. The agreed-upon strategy for 2005 through 2009 is to arrange annual workshops and training courses to build capacity among staff in national parks and provincial nature reserves in all Southern African countries and to also involve other stakeholders responsible for rock art promotion and management.

In 2009 the GCI assessed the work of the project over the 2005 to 2008 period. The aims of the assessment were to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the program in order to plan for future activities, and to secure agreement on contributions from prospective partner organizations in moving forward during 2010–2012. Feedback from past training participants was solicited through a questionnaire and face-to-face discussions. The assessment also included a meeting organized by the GCI and hosted by RARI, which was attended by a number of SARAP stakeholders, including from RARI, SANParks, CapeNature, the Tanzanian Antiquities Department, National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe, the Trust for African Rock Art, Leadership for Conservation in Africa, the Peace Parks Foundation, and training participants. These activities provided input to developing a slate of project activities for the 2010–2012 period.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation