Aron Mazel

Newcastle University and University of the Witwatersrand

& Ann Macdonald - Nyenganyenga Art and Design

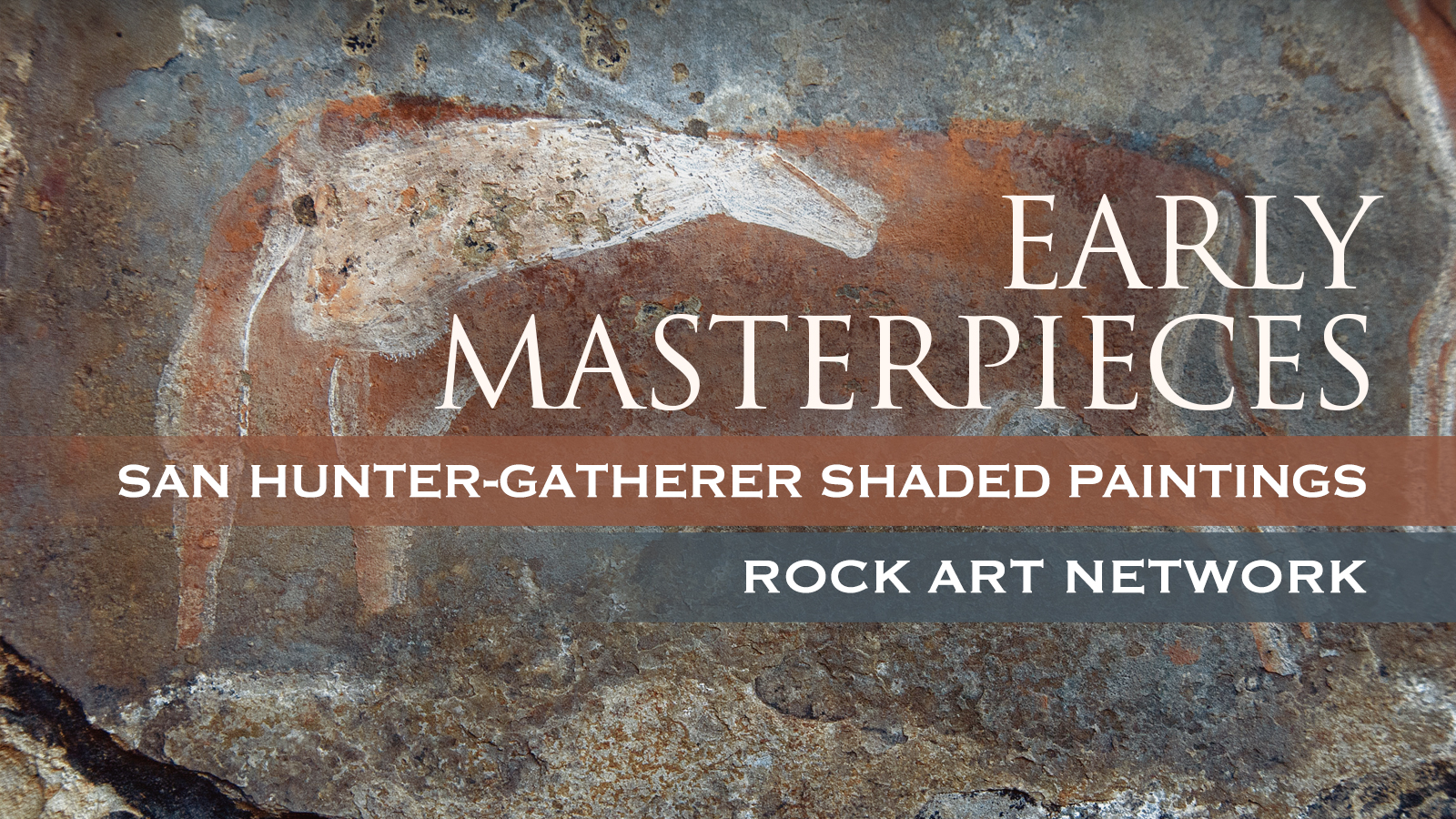

San hunter-gatherers are renowned internationally for their prolific output of rock paintings of mostly humans, animals, and ritual figures with spiritual meanings linked to trance rituals. We know this because our understanding of their art is grounded in in-depth ethnographic research. San hunter-gatherers painted a wide range of animals, with finely observed shape detail that produces a keen sense of movement and they shaded many paintings in vibrant earth colours. Eland and rhebuck were the most commonly shaded animals in uKhahlamba-Drakensberg and surrounding areas (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Strikingly, thousands of shaded forms that are polychromatic have been found in these areas. This polychromatic style is also present in other parts of South Africa and in Zimbabwe and Botswana but in considerably fewer numbers. If a masterpiece has the qualities of ‘outstanding artistry or skill’ (Oxford English Dictionary 2021) then we would say that San hunter-gather paintings, and especially the shaded polychromatic examples, qualify and can claim to be the first painting masterpieces in southern Africa.

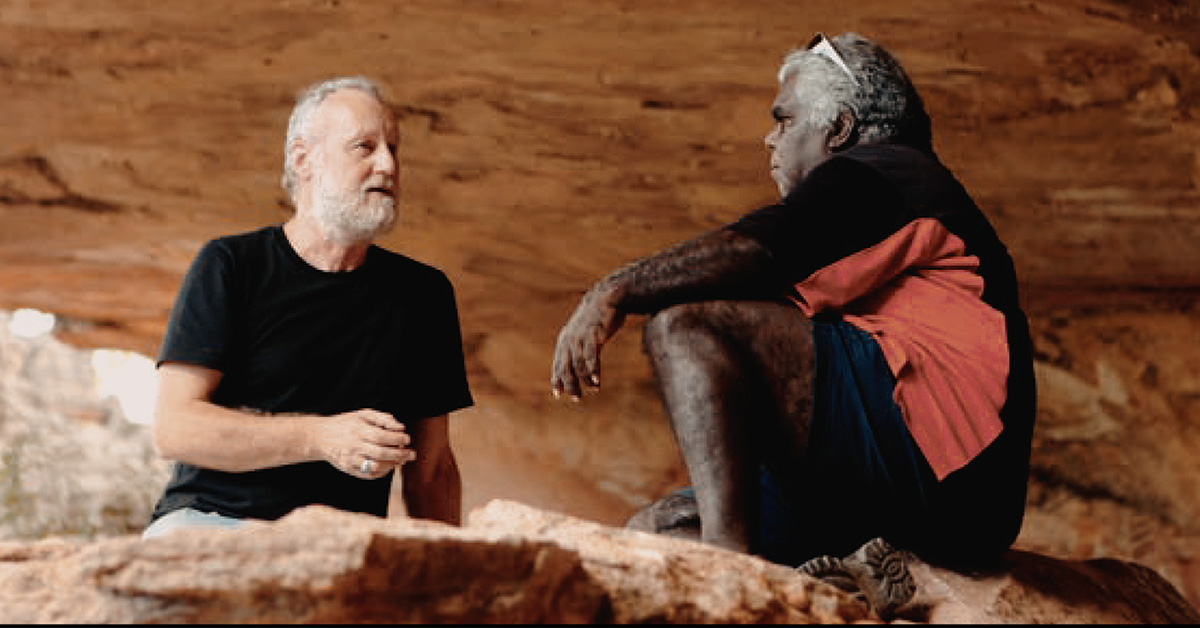

Mazel’s work, specialising in the uKhahlamba-Drakensburg (Figure 6 and Figure 7), has focused significant attention on not just recording and describing the paintings, but on trying to build a historical context around the data which he has amassed. For the shaded polychrome paintings, which stand out from the rest, this has begged the question of why the San were prompted to paint in this way. For many years, it was believed that they were created only in the last few hundred years as part of a linear progression in style complexity. It has been shown, however, that the San actually made them around 2000 years ago, and it has been argued that this was in response to the arrival of new people in the eastern part of southern Africa (Mazel 2009). Initially, the innovation of this more complex style, which is associated with the upsurge in the production of paintings, appeared to be a San response to the arrival of agriculturist communities moving down the African east coast around 2000 years ago. Re-examination of archaeological data in more depth has indicated that the San might also have experienced early encounters with pastoralists around the same time (Mazel 2013, 2021). So, the peopling of eastern southern Africa around 2000 years ago might have been more complex than originally thought.

Either way, the presence of new people on the landscape is likely to have shaken the San worldview and introduced hitherto unknown anxieties and challenges into their lives. This may have resulted in them not only expanding their exchange networks beyond existing boundaries (Mazel 2009; Mitchell 2009), but also increasing their ritual activity to ameliorate their anxieties, which in turn led to the proliferation of paintings accompanied by innovations, which included foreshortening and the making of shaded polychromatic paintings (Mazel 2009). This idea that increased stress resulted in heightened ritual activity is supported by work done by Guenther (1975-76) documenting the Kalahari San.

Drawing on insights from 19th and 20th century San ethnography and neuropsychological research, Lewis-Williams (2003) suggested that most if not all of the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg San rock paintings reflect the visions and experiences of medicine people in trance. In this state, they experience visual hallucinations that commonly take the form of images of the animals with which they fuse to enhance their own potency. In the Kalahari, San initiate trance dances by building a camp fire during the day. Dancing around the fire into the night then facilitates medicine people entering into trance. Being perceived as a strong stimulant, the fire plays a significant role in trance performances among the Kalahari San with its primary function to trigger n/um (i.e. energy), which assists in heating and controlling the dancer’s n/um (Katz 1982).

Transferring these insights into our understanding of San paintings, Lewis-Williams and Dowson (1990) commented: ‘In flickering firelight, paintings … probably assumed a three-dimensionality and life of their own … Paintings and the hallucinatory “motion picture or slide show” … would have melded one into the other’ In this scenario, it is likely that San shamans perceived actual eland, rhebok and other animals in the rock shelters when in trance, especially as the painted animals might have appeared bigger than they actually are on the walls of the rock shelters, perhaps even life size. Maqhoqha, whose father had been a shaman-artist, explained to Lewis-Williams (1986) and Jolly (1986), that shamans either touched or pointed at these ‘real and moving’ painted animals in order to harness their potency to achieve special powers. The ‘aliveness’ and power inherent in the walls of rock shelters would have been of great value to San shamans.

The San, therefore, may have innovated the polychromatic shading of paintings to increase their power. Laboratory experiments with shading and light have demonstrated that the interaction of these two variables produce a sense depth and motion. An experiment undertaken by Kleffner and Ramachandran (1992: 32) showed that ‘The extraction of shape from shading can also provide an input to motion perception.’ Moreover, it has been shown that the perception of depth and motion in shading may derive from the light source being at different angles, including from below (Morgenstern et al. 2011; Proulx (2014). With trance fires functioning as has already been discussed, such firelight in illuminating the shaded paintings in shelters likely evoked powerful stimulants for trance, serving to alleviate anxiety and stress.

It is, therefore, suggested that the San innovated the shading to give depth and motion to the paintings in order to increase their power. In essence, the shading of paintings was a deliberate stylistic feature used by the San to enhance the power of the paintings, which intensified their trance experience, as they believed that the animals whose power they were drawing on were not only present in the painted shelters but were also moving. This would have helped the San cope with the anxieties and stresses associated by the emergence of new people onto the landscape around 2000 years ago.

Guenther, M.G. 1975–76. The San trance dance: ritual and revitalization among the farm Bushmen of the Ghanzi District, Republic of Botswana. Journal of the South West Africa Scientific Society 30: 45–53.

Jolly, P. 1986. A first-generation descendant of the Transkei San. South African Archaeological Bulletin 41: 6–9.

Katz, R. 1982. Boiling Energy: Community Healing among the Kalahari !Kung. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kleffner, D. A. and Ramachadran, V.S. 1992. On the perception of shape from shading. Perception & Psychophysics. 52 (1): 18–36.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1986. The Last Testament of the Southern San. South African Archaeological Bulletin. 41: 10–11.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 2003. Images of mystery: rock art of the Drakensberg. Cape Town: Double Storey.

Lewis-Williams J. D. and Dowson T. A. 1990. Through the Veil: San Rock Paintings and the Rock Face. South African Archaeological Bulletin 45: 5–16.

Mazel, A.D. 2009a. Unsettled times: shaded polychrome paintings and hunter-gatherer history in the southeastern mountains of southern Africa. Southern African Humanities 21: 85–115.

Mazel, A.D. 2013. Paint and earth: constructing hunter-gatherer history in the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg, South Africa. Time and Mind 6 (1): 49–58.

Mazel, A.D. 2021. Mountain living: The Holocene people of the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg, South Africa. Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2021.04.039

Mitchell, P. 2009. Hunter-gatherers and farmers: some implications of 1,800 years of interaction in the Maloti-Drakensberg region of southern Africa. In K. Ikeya, H. Ogawa and P. Mitchell (eds) Interactions between Hunter-Gatherers and Farmers: from Prehistory to Present. Senri Ethnological Studies 73: 15–46.

Morgenstern, Y. Murray, R. F. and Harris, L. R. 2011. The human visual system’s assumption that light comes from above is weak. PNAS 108 (30): 12551–12553.

Proulx, M.J. 2014. The perception of shape from shading in a new light. PeerJ 2:e363.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation