by Johannes H. N. Loubser

Stratum Unlimited

This paper calls for the recording of graffiti, including those that are to be removed and the ones deemed sufficiently significant to be left intact. Where graffiti is overwhelming and time consuming to record in detail, it remains worthwhile to record at least the dates and significant names (seemingly meaningless letters and faint or illegible scribbles on rock surfaces can be photographed, but are arguably a waste of time to record thoroughly, particularly when it comes to tight time schedules and budgetary constraints).

During my rock art documentation in different parts of North America, it has become apparent to me that recorded graffiti dates can throw suggestive light on visitation trends. When compared to the documented history of changing land ownership, population growth, and extra-local events, then fluctuations in date numbers reveal certain suggestive visitation trends. Knowledge derived from past visitation patterns and behavior as suggested by graffiti dates may assist rock art site managers to make more informed decisions concerning effective conservation strategies.

At the outset it is worth mentioning that graffiti dates, be they incised, drawn, or painted, are not one-to-one indications of when a site was visited. Many people simply leave their names, initials, and hometown and state names without a date of their day of visit; it is not known what proportion of visitors included dates as part of their graffiti. Dates may moreover indicate an event, real or imaginary, that occurred in the distant past, such as birth dates, historic events of significance, or made-up dates. However, for the purposes of this article, it is assumed that most dates do indeed reflect the actual year, month, and/or day of visit. This assumption is justified by various contextual assessments. For instance, many law-enforcement cases have been successfully solved by using graffiti dates as evidence. Also, juxtaposed family names on a rock surface often contain the same day of visit. Where dates differ, such as showing successive days, months, or years, local visitors consulted have confessed that the dates accurately reflect re-visits.

With this caveat in mind, graffiti date trends are discussed at the following four sites: Scenic Mountain (western Texas); Painted Rock (southern California); Writing-on-Stone (southern Alberta); and Castle Gardens (central Wyoming). Similarities and differences in visitation trends hopefully will help site managers to make informed decisions as to if and how rock art sites are to be opened to a visiting public.

Scenic Mountain is a 210-foot high limestone mesa overlooking the City of Big Spring in western Texas (Figure 1). Located within Big Spring State Park, a total of 376 incised graffiti panels have been located at 11 different loci on Scenic Mountain (Figure 2). In an effort to preserve the meticulously-executed graffiti, much of which dates back to the early twentieth century within the park, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department requested an inventory to be made of all graffiti and the formulation of recommendations to best conserve the integrity of the historic graffiti and their setting (Mark et al. 2009). In addition to the incised letters, numbers, and Euro-American style drawings, a single incised horned-face motif stylistically resembles precontact Indigenous painted lined and horned faces on the rock surfaces of Hueco Tanks in far western Texas (see Sutherland 2002:11-22).

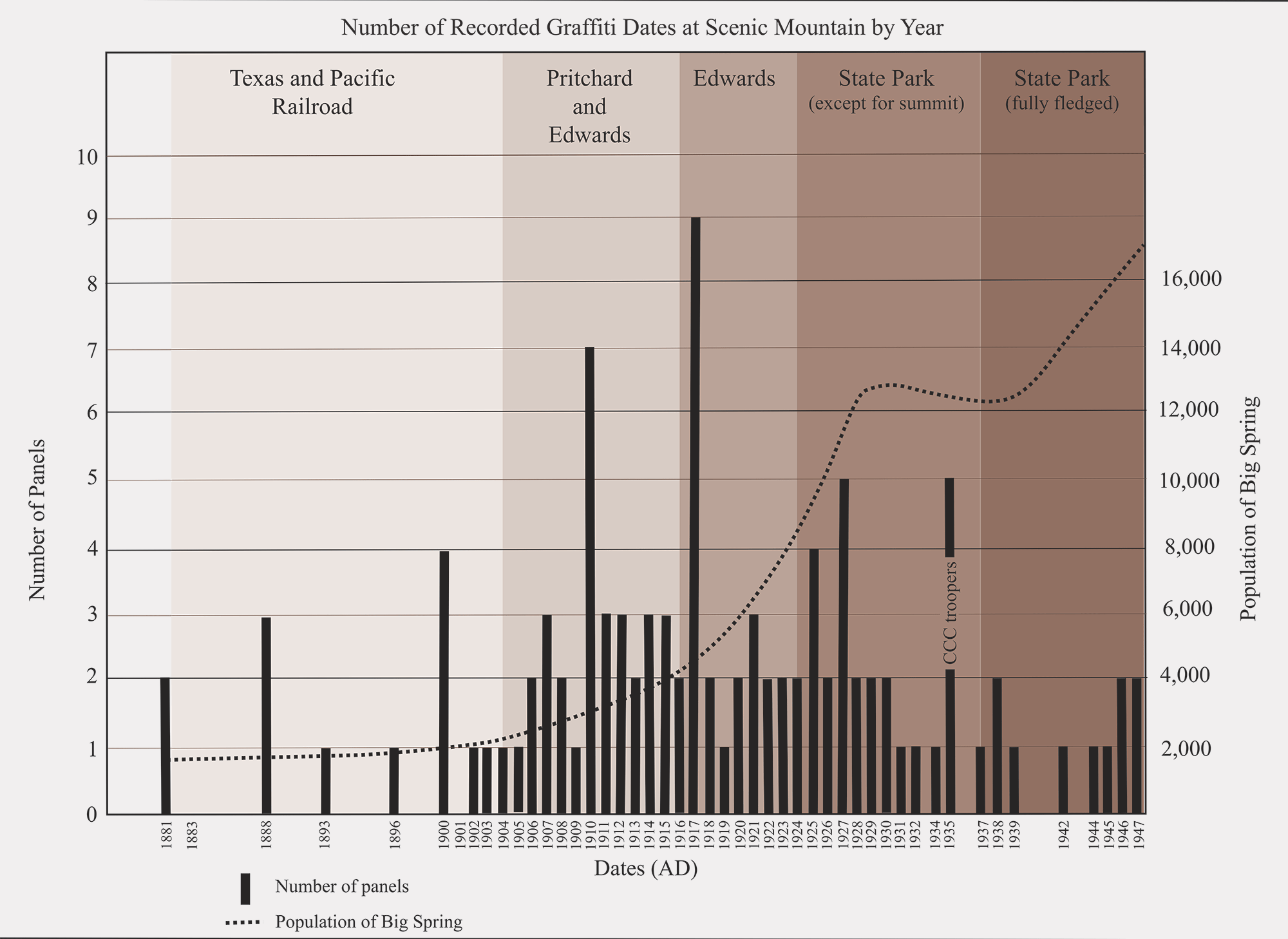

Based on the documented history for Scenic Mountain, the following four phases of ownership, management, and associated visitation can be identified (Figure 3): 1.) the Texas and Pacific Railroad era (1881 to 1916) when people regularly visited Scenic Mountain from the city of Big Spring to the northwest; 2a. and b.) the Edwards era (from 1916 to 1934, which includes 2a.Edward’s initial co-ownership with Pritchard and 2b. Edward’s sole ownership of the mountain top) characterized by the mountain apex being used as privately owned pasture, but continued to being visited by people from the city of Big Spring; 3.) the early State Park/Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) era (1934 to 1936) when built structures and roads significantly altered the Scenic Mountain landscape, but the mountain top still being privately owned; and 4.) the fully-fledged State Park era (1937 to present) when the land was actively managed by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department for public recreational purposes, including nature watching, hiking, jogging, and picnicking.

Diagrammatic Representation of Graffiti Dates at Scenic Mountain.

According to Figure 3, there is no clear relationship between the number of graffiti panels completed per year and the growing population of Big Spring (i.e., as based on population totals cited in Hazlewood and Odintz 2008). Judging from the peaks of engraved date frequency, the years between 1910 and 1917 appear to be comparatively active, which coincides with Edward’s private ownership of the land. The isolated burst of activity from 1934 to 1936 represents CCC troopers within the park. When Edwards finally sold the summit of the mountain to the state in 1937, graffiti rates appear to have declined. Overall, the graph suggests that intensity of engraving on Scenic Mountain is probably a result of fashionable trends rather than population or visitation numbers. Judging from those dates that indicate months, most of the engravings appear to have been done during the winter (Figure 4), when cooler weather favored visits to the mountain top and graffiti application. July is an aberration within this trend, most likely due to people visiting the mountain top on Independence Day, despite very high summer-time temperatures.

The name “Leonard Fisher,” which is done meticulously in Gothic script, dates to “12-6-16” (Figure 5). Leonard Fisher is a member of the well-known Fisher family of dry-good merchants in nearby Big Spring (e.g., Pickle 1980:241, 423). Another Big Spring resident, “Barney Lee Russell,” had engraved his name in a similar tidy Gothic font nearby. Technically and aesthetically-speaking, the carefully and evenly carved letters of these and other roughly contemporary graffiti names, which roughly date to between 1916 and 1934 (labeled the Edwards-era), are among the best executed in the Big Spring State Park. Partly due to the artistic skill exhibited by these and other roughly contemporary names, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department wants to preserve them for future generations to view and enjoy.

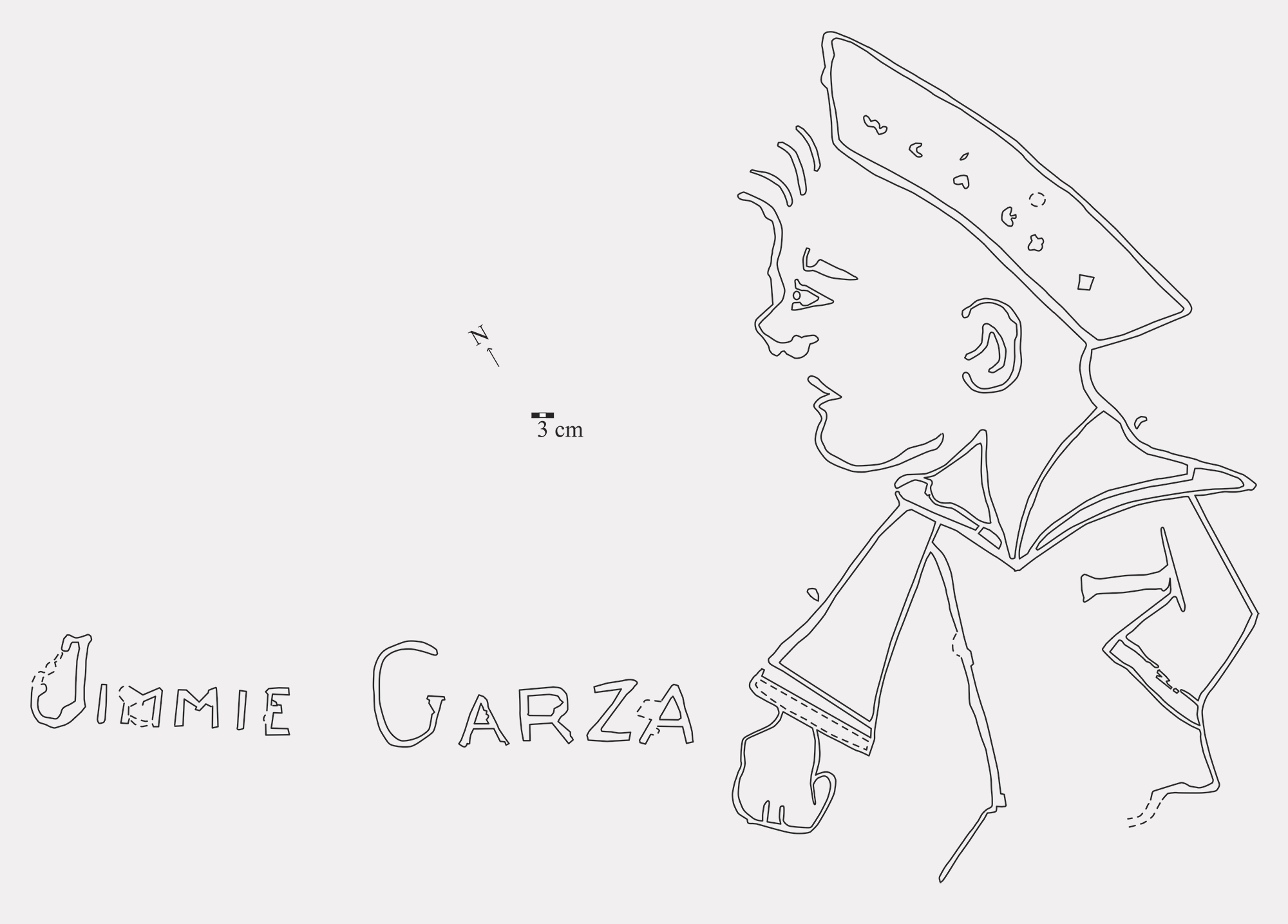

The CCC-era panels likewise exhibit artistic and technical skill. For example, the CCC-era panel with name “JIMMY GARZA” occurs next-to a finely executed pecked and incised cartoon-like depiction of a “sailor” (Figure 6). The head and cap are enlarged in proportion to the body. Based on the absence of the figure’s left hand and legs it is safe to infer that it was never completed. The name Jimmy Garza is listed on the roster of CCC Company #1857 (Treanor 1994). This company quarried limestone blocks nearby for the construction of rustic features on the park, between the years 1934 and 1935.

The Edwards (1916 to 1934) and CCC-era (1934 to 1936) carvings clearly have sentimental value to members of the local community and more distant towns, many of whom are continuing the tradition of finding and viewing the graffiti carvings left by their ancestors on top of Scenic Mountain (e.g., Atwell 1982:28).

Sloppy-looking graffiti names and dates have generally been applied in a hurry by more recent day-time visitors, who for the most part have travelled from other parts of the country. Few or any of these later names are associated with places that are tied to Scenic Mountain in the same way as the meticulous earlier ones that were done by local inhabitants. But more pertinently, jumbled expanses of recent graffiti tend to overwhelm and obscure the earlier names and dates. In order to preserve the character and integrity of the pre-1950 graffiti and the single Native American motif within the Big Spring State Park, it has been recommended that all post-1950 graffiti should be removed (Mark et al. 2009).

View of Painted Rock from its Northern Entrance, southern California.

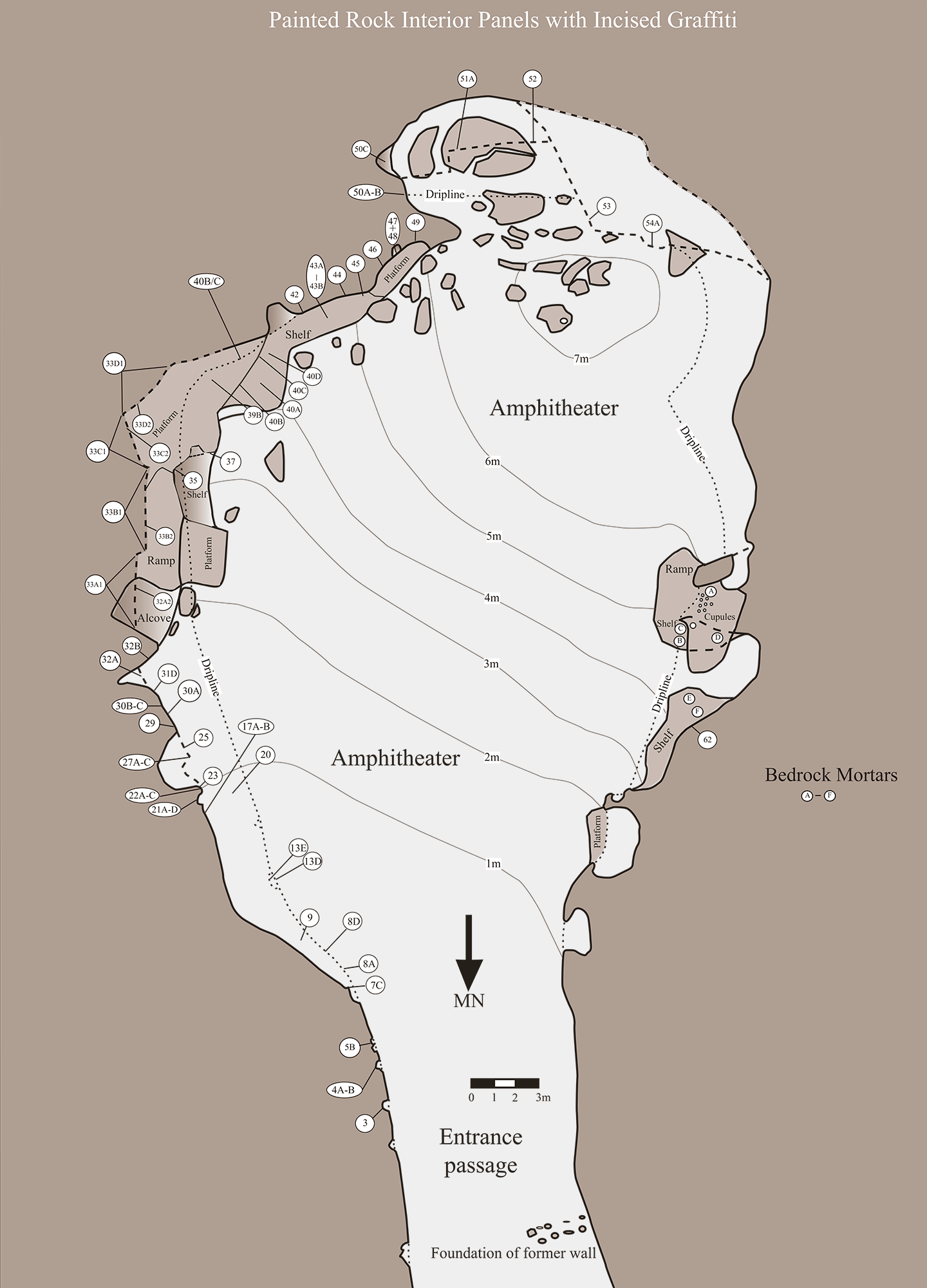

The concentration of incised graffiti within the amphitheater made it necessary that the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) focuses its 1991 graffiti camouflage efforts on this highly visible and much-visited section of Painted Rock (Thorn 1991). Most of the graffiti within the amphitheater was either completely removed or camouflaged. A couple of historic period names and images have been left intact, notably the name and date "Geo. Lewis 1908,” the founder of Atascadero, California.

All-in-all it can be said that graffiti at Painted Rock was applied to those surfaces that are readily visible to the casual visitor; any surfaces hidden behind drip lines and/or require one to get down into a crawling or slithering position did not contain graffiti. The fact that many of the less visible and/or low-lying pictograph panels did not contain graffiti suggests that the intent of these pictographs is different from that of graffiti. As will be seen below, the placement of graffiti within the Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park in Alberta, Canada, include obscure locations, such as within alcoves and behind sandstone pillars.

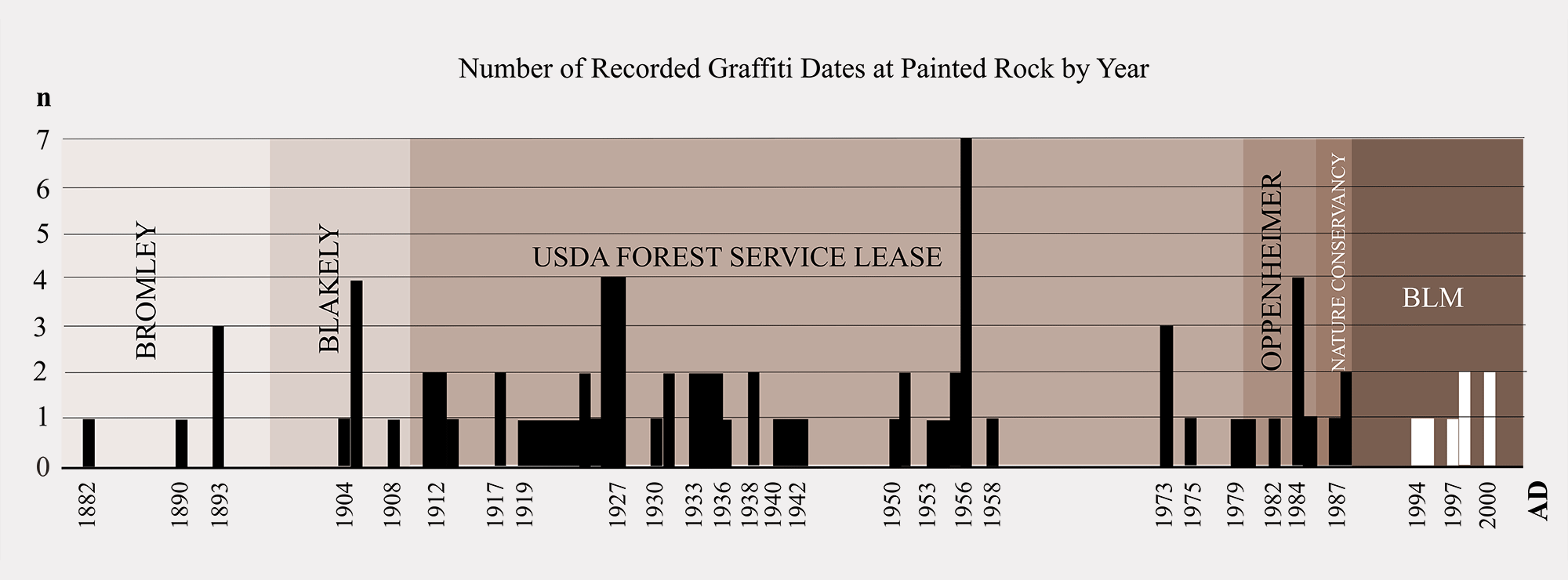

Based on the documented history for Painted Rock, the following four phases of ownership, management, and associated visitation can be identified (Figure 9): 1a. and b.) the era of private ownership which includes first 1a.the Bromley and then the 1b. Blakely families (1880 to 1910), with friends and family visiting Painted Rock on an intermittent basis, often in horse-drawn carriages; 2.) the USDA Forest Service lease era (from 1910 to 1980) characterized by varied, but often intensive visitation; 3.) Oppenheimer ownership of Painted Rock (1980 to 1985); 4) the short-lived Nature Conservancy era (1986 to 1988) which marked an increased awareness of visitor behavior; and 4.) the BLM era (1989 to present) when the land was actively managed to conserve nature and culture, to conserve the remote character of the landscape, and to support academic inquiry into resource management and public education.

The National Motorist Magazine of 1926 advertised Painted Rock as a tourist attraction (Werden 2008:29). As can be seen from old photographs and various accounts, by the 1920s the site has already been a well-known and frequently visited destination. Although exact visitor numbers are unknown, it is estimated that roughly 3,000 people visit Painted Rock annually. The site is closed to visitation from March 7 to June 15 due to raptor season. The highest visitation is in Spring, followed by Fall, and Summer months (Duane Christian and Tamar Whitley, personal communication). Visitation varies from year to year, depending on temperatures, precipitation, or good flowering season. This variation in visitation implies that people visit the rock and its surrounding area primarily for reasons other than rock art. Since 1989 the access road that leads directly to the northern entrance of Painted Rock’s amphitheater has been closed, so that visitors now must approach the site via a 0.75-mile trail. Clever use of fencing excludes cattle and channels visitors to the trail head. Any locations with potentially new graffiti are noted during monitoring. These are compared with earlier photographs taken by GCI in 1991. The monitoring is done by trained volunteers from the Southern Sierra Archaeological Society and BLM staff. BLM staff archaeologist, Monument staff, and volunteer site stewards make additional visits to site.

If incised graffiti dates within the amphitheater are taken at face value (as recorded during the GCI’s 1991 field season and by post-1989 field monitors for the BLM), then vandalism was intermittent during the late nineteenth century era of private land ownership (Figure 9). Vandalism became much more frequent in the early twentieth century, peaking in 1927, which is early on during leasing of land by the USDA Forest Service. It is during this period that ranching gave way to agriculture; from the 1920s to 1930s mechanized tractors cultivated large tracks of Carrizo Plain for dry-farmed wheat. But more than anything else, the 1920s oil boom brought thousands of people into the Carrizo region and automobiles made it easy for tourists to visit Painted Rock. Visitation to the site seemingly taking a break during the 1940s, which is likely associated with World War II. Graffiti picked up considerably in the 1950s, peaking to an all- time high in 1956. Painted Rock apparently experienced another “clean” period during the 1960s. The 1970s and 1980s were years of sporadic vandalism, ostensibly ceasing in 1987, when it was incorporated by the Nature Conservancy and the road leading up to Painted Rock was closed. Following the GCI graffiti removal exercise in 1991, graffiti re-appeared in 1994, albeit in limited numbers. Most of the post-1991 graffiti is juxtaposed or superimposed on pre-1991 graffiti that is still visible; it can be said that this faintly visible graffiti begot additional graffiti. Fortunately, however, none of the post-1991 graffiti has been placed on top of rock art.

A new strategy of visitation to Painted Rock has recently been implemented, one in which unguided visits to the site requires a BLM permit (Tamara Whitley, personal communication). A permit can be obtained online at Recreation.gov. Guided tour bookings can be done on the same web site. Under the new permit system, Painted Rock continues to have the same “closed” season as before (i.e., March 7 to June 15), with guided tours available every Saturday from March 16 to the end of May.

To maintain the spiritual, research, and aesthetic integrity of Painted Rock, the BLM staff archaeologist, Monument staff, and the volunteer site stewards regularly visit the site. However, the few remaining visible graffiti at the site might prompt visitors to add their own initials, names, and dates. The choice is between creating a clean slate at the site or run the risk of leaving graffiti remnants that may inspire more graffiti in the future.

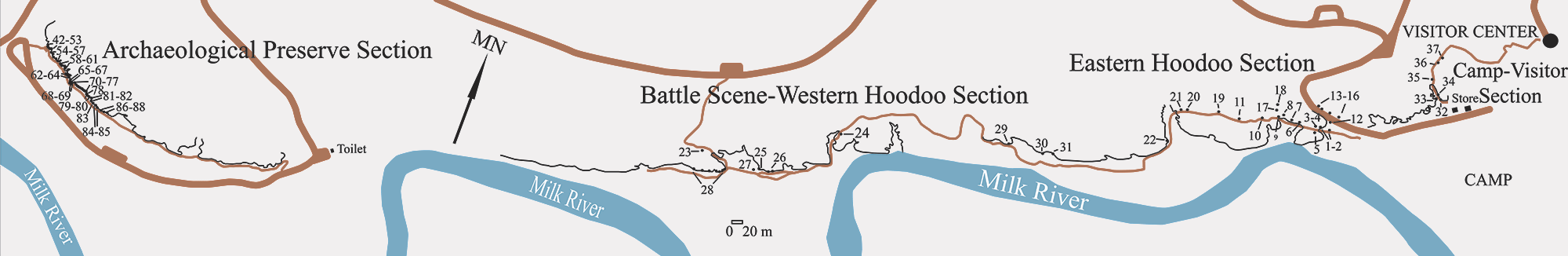

View of Writing-on-Stone Archaeological Preserve from the Milk River, southern Alberta.

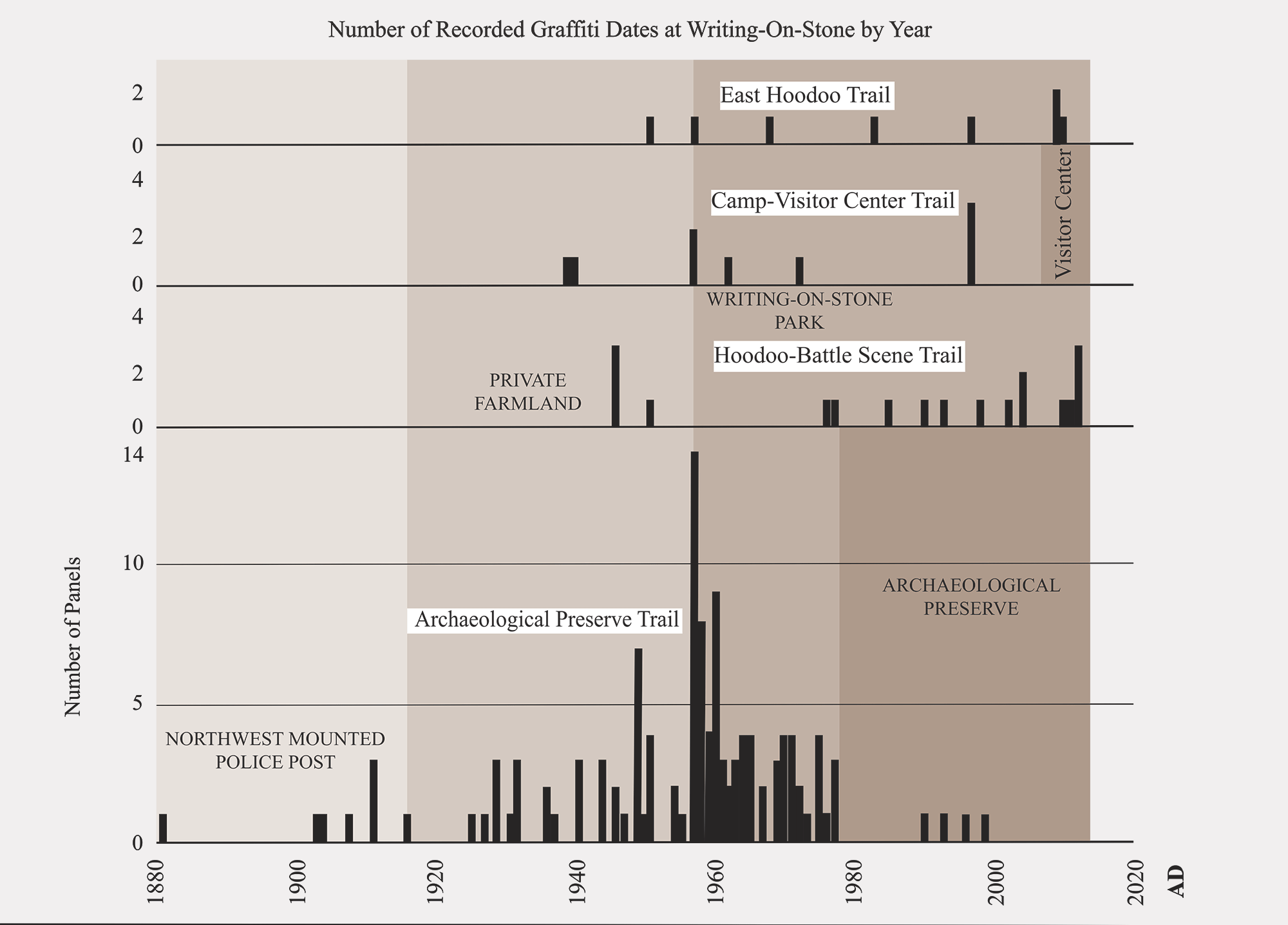

Diagrammatic Representation of Graffiti Dates at Different Locations within Writing- on-Stone.

Taking the incised dates at face value, the earliest graffiti was done within the area that is currently designated as the Archaeological Preserve, dating to 1851 (Figure 12). The next date thereafter is 1881. Both dates precede the establishment of a North-West Mounted Police (the precursor of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) camp across the Milk River from the site in 1887. The oldest recorded date along the western hoodoo-Battle Scene trail is 1904. It is during the period immediately preceding World War I that ranchers and farmers settled in the area. After the closure of the North-West Mounted Police outpost in 1918, graffiti continued to be applied on the rock surfaces what later became the Archaeological Preserve. In 1939 the first recorded date appears among the scenic hoodoos that are sandwiched between the campground and the later visitor center. These historical graffiti are valued and were not removed. By 1951 the graffiti is present in the hoodoos along the current eastern hoodoo trail. The park was created in 1957, which is the year with the most recorded incised dates (i.e., 14 within what became the Archaeological Preserve and one along the eastern hoodoo trail). After the designation of the Archaeological Preserve in 1977, graffiti virtually disappeared, the last incised date recorded being 1999. This is also roughly the time that graffiti declined along the campground trail, which is some time before the opening of the visitor center in 2007. The most recent date along the eastern hoodoo trail is 2010. The three separate 2012 dates that were recorded along the western hoodoo-Battle Scene trails indicates that graffiti application is an ongoing problem in this area. During removal in the field, we witnessed visitors inscribing their initials on the rock near the corner where the trail linking the car park with the Battle Scene site comes very close to the rock surface.

As can be seen in Figure 12, by 1957, when the park was formally designated, a popular pastime among outside visitors was scratching their names and dates into the soft sandstone, particularly near the public facilities and on the most accessible rock art panels. At an increasing rate, the damage was done largely by people without a personal or historical connection to the place. Regardless of their ostensible interest to view the Indigenous rock art, outside visitors continued to graffiti the rock well into the 1970s (Klassen 2007:32). Ever since 1977 when guided interpretive tours to select rock art panels started within the Archaeological Preserve, the incidence of graffiti application has decreased significantly.

Incised names and dates, a few historic period motifs, and bullet holes occur either separately or on top of the Indigenous petroglyphs and pictographs along portions of the cliffs. While some graffiti occurrences are important to the history of the park and surrounding community, the vast majority of historic period names, dates, and motifs were done by people who have visited the place very briefly and have little to no knowledge of its significance. Considering that much of historic period graffiti (with the exception of North-West Mounted Police and early homesteaders who lived in the area for a long time) bears no intrinsic relationship to Writing-on- Stone as a place, the presence of such graffiti distracts from its significance values. Historic period graffiti also covers and obscures from view much of the original Indigenous petroglyphs and pictographs. In a few instances deep gashes created by historic period graffiti in the rock surface have facilitated accelerated weathering of the softer matrix deeper within the rock. So, in terms of historic period graffiti compromising the integrity, reducing the visibility, and increasing the vulnerability of indigenous rock art, it was requested that they be removed.

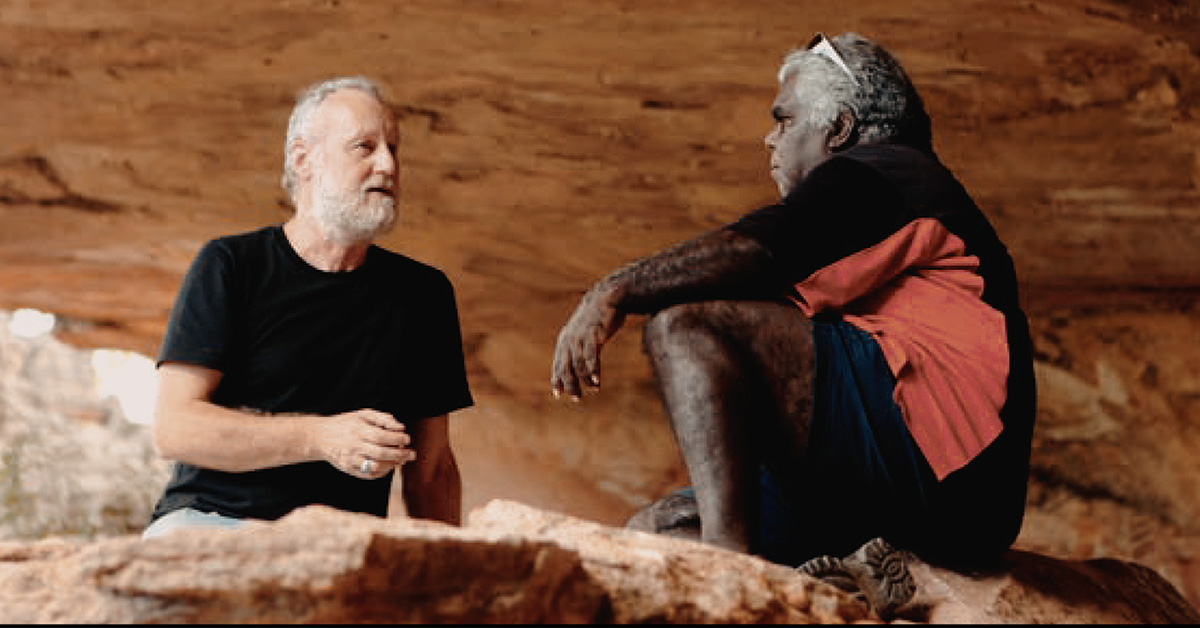

Care was taken when removing historic period graffiti in case they may be associated with the North-West Mounted Police presence in the area. Care was also taken not to remove names and dates left by early Euro-Canadian homesteaders who farmed the area, mostly between 1905 and the 1930s. Following on-site consultation with a group of local farmers, the following names and initials were left intact: “B. Lippa;” “W. Bruce;” “J. Kolesar;” “B.L.;” “O’Hara;” “Loretta Thielen;” “D.E. Scott West;” “Ted Humphrey;” “Lyle Pittman;” “Garvin Gaehring;” “H. Audet;” “Wally M. Fingers;” and “G. L. Hutchinson.” Very likely for sentimental reasons, at least some descendants of these pioneer farmers and ranchers still visit the cliffs to view the names of their ancestors. Notable Blackfoot elders who visited the site in 1957 outlined the following incised text, which is very weathered and not completely legible anymore: "ALL FROM LANDN... STAB.DOWN, THE SHOUTIMEISR, ...MELMTEDH, JOHNNY HEALY, OCT 1957." This Indigenous writing was left intact.

Unlike Painted Rock, where graffiti tended to occur within full sight of visitors, graffiti within Writing-on-Stone also occur in alcoves or behind sandstone pillars that require crawling or climbing. Invariably, however, graffiti almost always occurs near trails (i.e., including old, new, formal, or informal) and tend to concentrate near Indigenous rock art panels.

To discourage unwanted graffiti from recurring within the park, it is recommended that the trails closest to the rock surfaces be re-vegetated and that the use of the alternative trail downslope and farther away from the cliff face be encouraged. It is only where there is a barrier between the trail and petroglyph/pictograph panel, such as a fence and/or interpretive sign and/or thorny shrubs, when pedestrians should be encouraged to come closer, especially where there are readily visible petroglyphs and/or pictographs worth seeing.

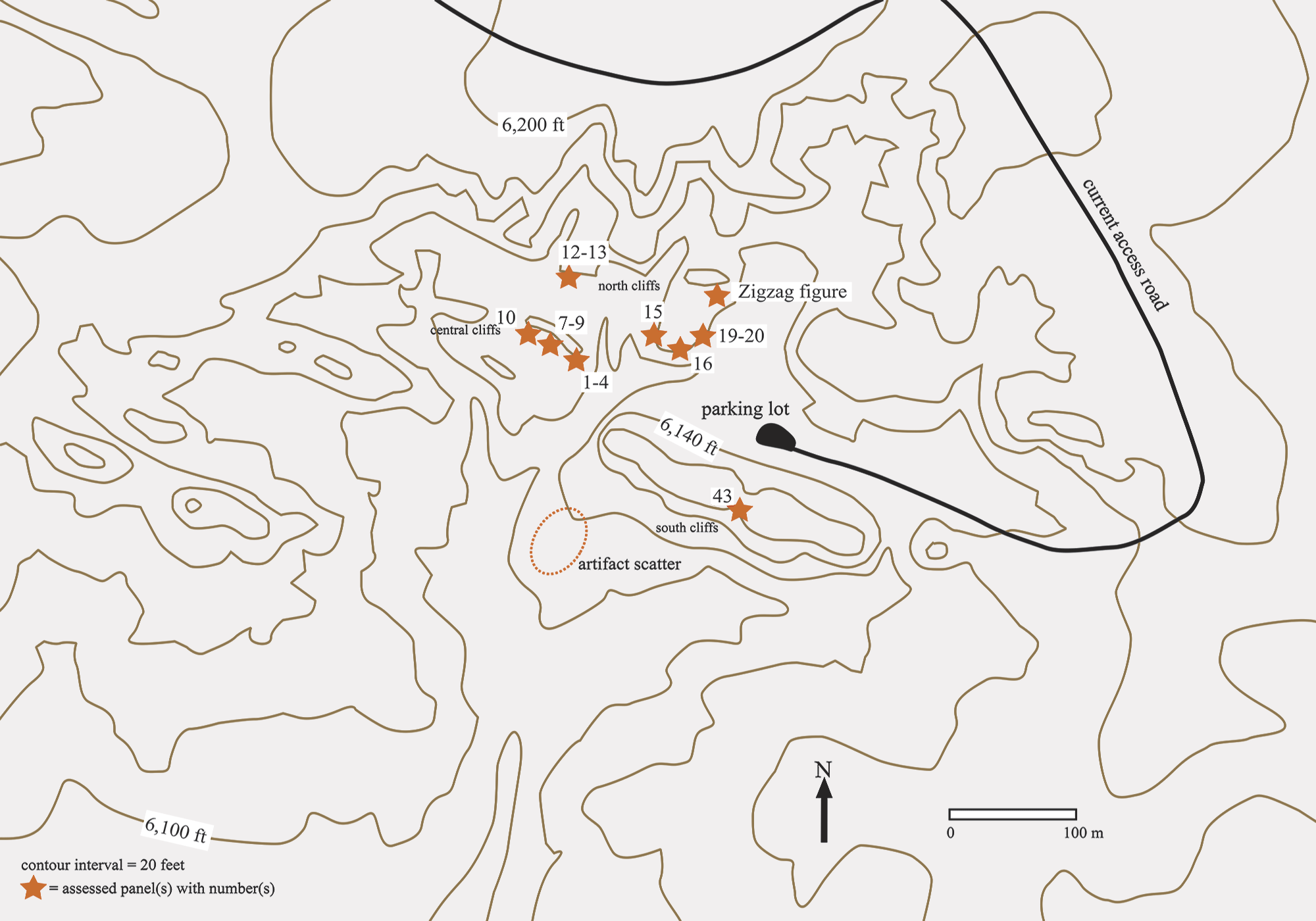

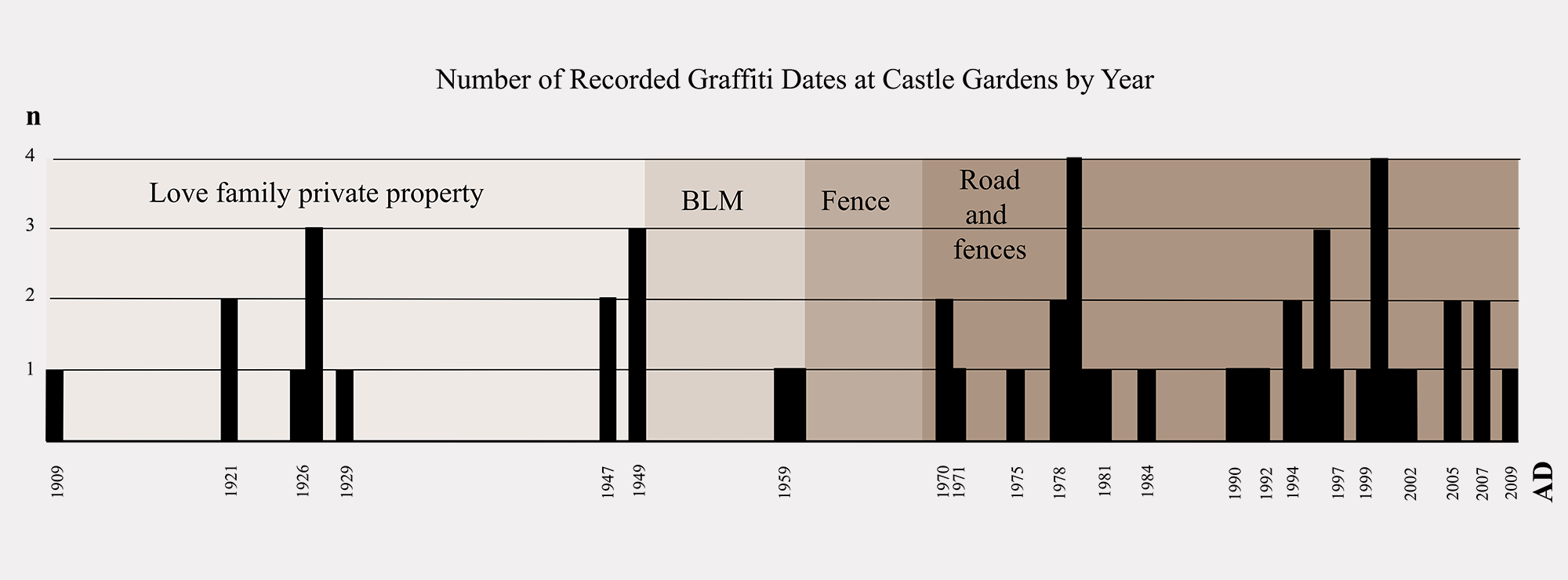

Castle Gardens comprises a series of roughly parallel southwest-facing sandstone cliffs, on average 10 feet high, which project sharply above the concave floor of an eroded upper watershed drainage basin (Figure 13). At least 57 petroglyph panels have been recorded within the upper drainage area (Gebhard et al. 1987), of which 16 were condition assessed (Figure 14). Based on the results of the condition assessment (Loubser 2010), the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) requested that graffiti be removed from all surfaces visible from the trail that connects 15 of the most visited rock art panels (graffiti was removed from 101 panels in 2010). Located in central Wyoming, the Castle Gardens rock art complex is significant within the plains as it contains a comparatively varied and detailed collection of petroglyph and pictograph panels. Most of the petroglyphs at Castle Gardens were probably done by the Eastern Shoshone prior to their full-scale acquisition of the horse (Gebhard et al. 1987:14).

Map of Castle Gardens, Showing Location of Old Car Park and Rock Art Panels.

Diagrammatic Representation of Graffiti Dates at Castle Gardens.

Reminiscent of graffiti within Writing-on-Stone, vandalism at Castle Gardens also occur in alcoves or behind sandstone pillars that require crawling or climbing. Invariably, however, graffiti almost always occurs near trails (i.e., including old, new, formal, or informal). However, unlike Writing-on-Stone, graffiti is not always denser closer to rock art panels.

Most graffiti occur within easy walking distance from the current parking lot. To discourage unwanted graffiti from recurring at Castle Gardens, it has been recommended to move the access road and parking lot some distance away from the rock art panels. Also recommended are installation of interpretive pedestals at the fenced panels and the implementation of a site stewardship program.

In the absence of a pro-active management infrastructure, visitors tend to set the management standards, often to the detriment of the sites and associated art. It can be argued that good site preservation is really all about good presentation to the visiting public. For example, if a site has graffiti and appears untidy and uncared for, then visitors cannot take all the blame for not taking care or for behaving inappropriately. Clean rock surfaces devoid of graffiti and clean deposits without litter or detritus create a good impression. Moreover, with the agreement of Indigenous and other stakeholders, the installment of interpretive signage and clearly delineated and well- maintained trails create a sense of official presence and custodial care.

A common trend at all four sites is that graffiti does not necessarily increase with increasing population or increasing visitation numbers. A shared reason for the increase in graffiti rather appears to be increasing access to unmanaged sites, be it through opening them to the public (e.g., Scenic Mountain during Edwards ownership in the early 1900s or Writing-on-Stone becoming a provincial park in 1957) or constructing new roads to within easy walking distance of the sites (e.g., Castle Gardens in 1968). Closure of roads (e.g., Painted Rock since 1989), entrance via guided tours only (e.g., the Archaeological Preserve at Writing-on-Stone since 1977), and increased monitoring by park staff (e.g., since the 1990s at Scenic Mountain) have been accompanied by a rapid drop-off in graffiti incidences. Effective presentation of appropriate interpretive material should also go a long way towards informing visitors and discouraging graffiti. On rock surfaces where historic period graffiti has been left intact, interpretive signs and/or brochures should state the reason why the graffiti is significant and worth preserving. Positive signage, such as “please help us preserve these rare rock markings by staying on the pathway,” should help foster a feeling of custodial care among visitors. Future systematic recording and removal of graffiti at other petroglyph and/or pictograph sites are likely to yield interesting results as to past visitation patterns and behaviors. Knowledge likely to be gained might help with the pro-active and sustainable management and conservation approach already adopted by site managers.

In alphabetical order, the following people are thanked for contributing towards the success of the graffiti recording and removal efforts at the sites mentioned in the text: Ron Alton; Jack Brink; Craig Bromley; Karina Bryan; Aaron Domes; Dabney Ford; Jane Kolber; Tony Lyle; and Tamara Whitley.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation