Exhibition organized by the National Museum and Research Center of Altamira (Spain)

Curator

Carolyn Boyd

Texas State University | Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center

Coordinator

Pilar Fatás

Museo de Altamira

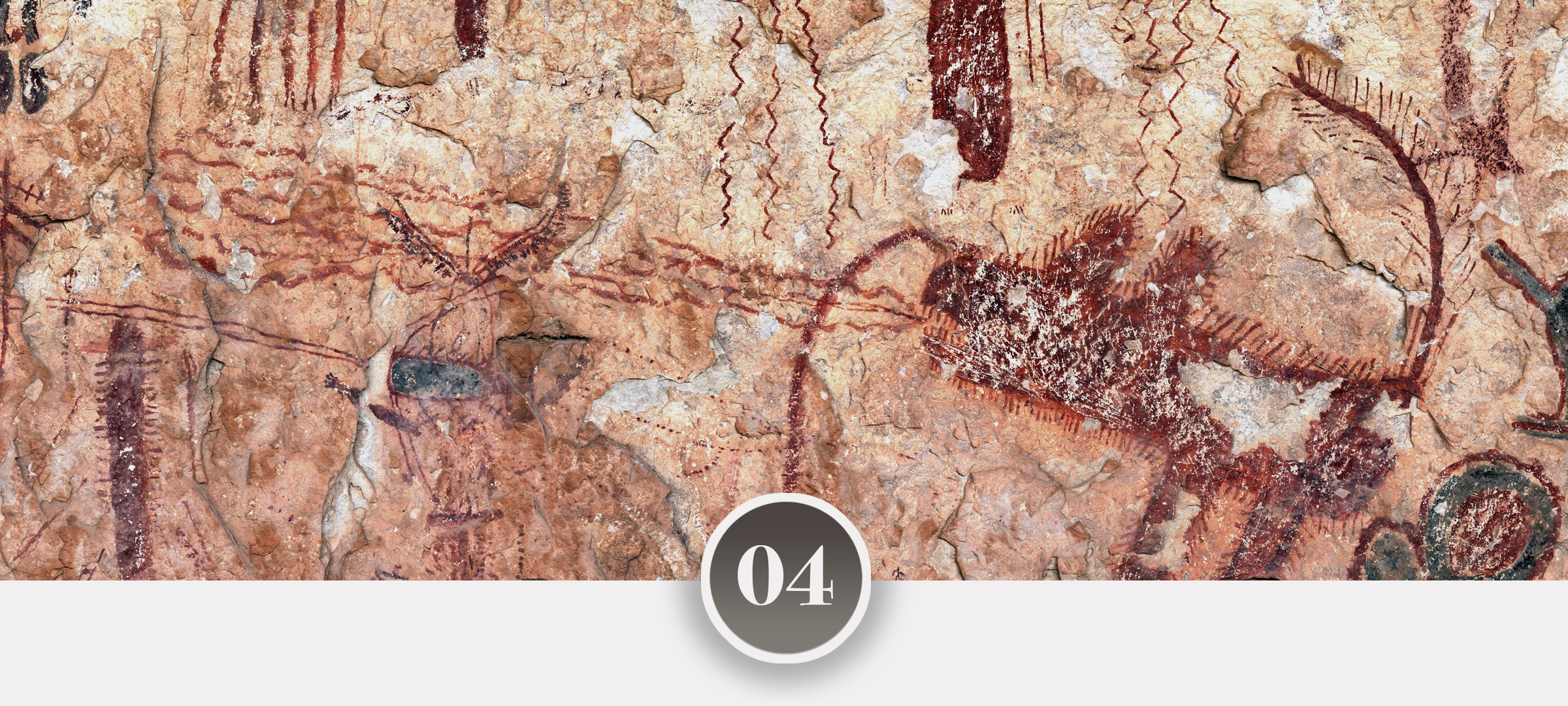

Almost 4,000 years ago, in southwest Texas (USA) and Coahuila (Mexico), hunter-gatherer artists painted some of the most complex murals in the world. They wove together layers of black, red, yellow, and white paint to create visual narratives. In Indigenous realities, images such as these are not passive decorations. They are reservoirs of power actively engaged in creation-past, present, and future. This exhibit explores how form, color, materiality of the paint, and the image-making process infused the murals with meaning and activated the characters in the stories they relate.

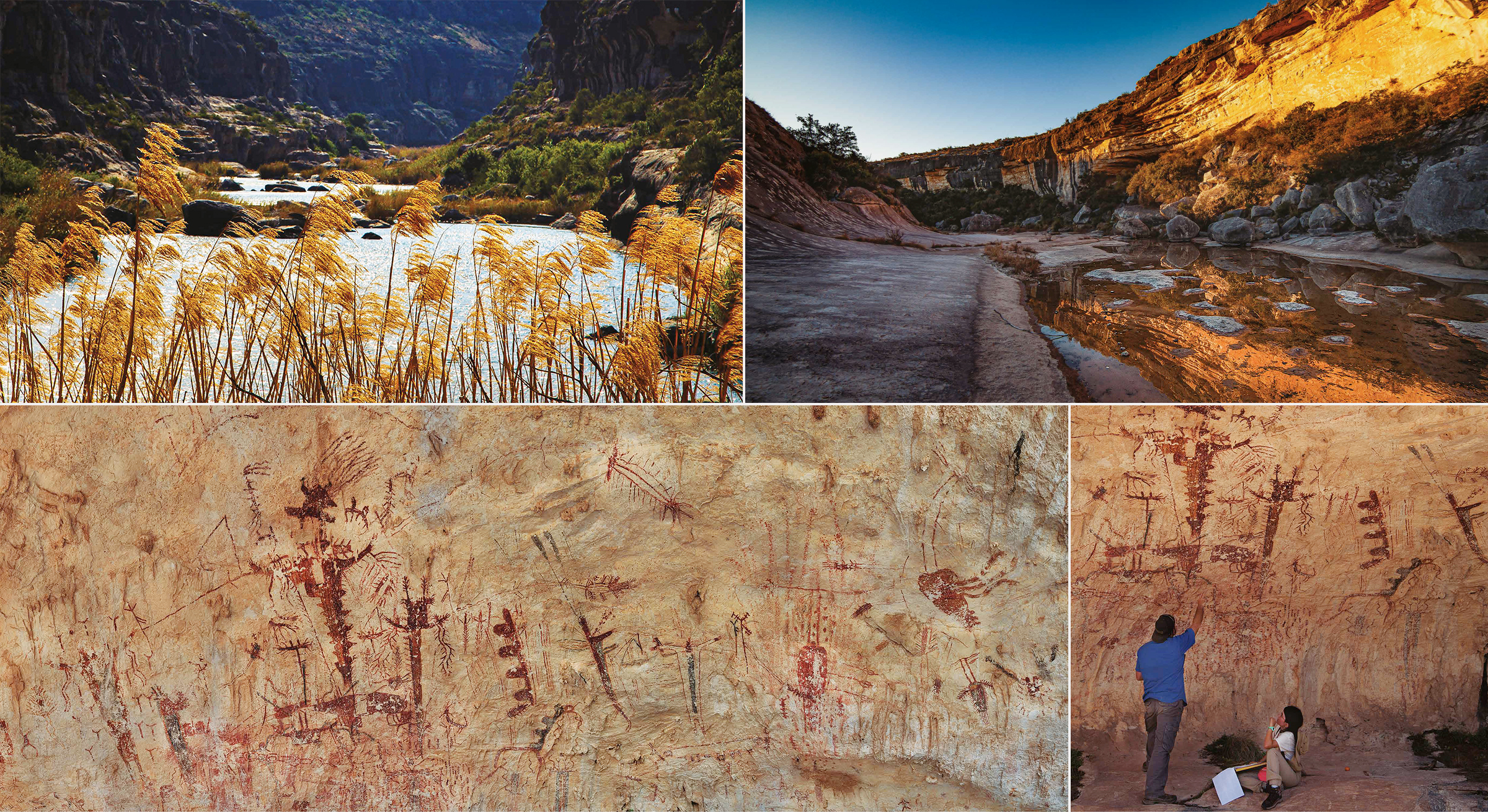

THE REGION

The Lower Pecos is a dramatic landscape incised by deep and narrow canyons holding hundreds of dry rockshelters. Within these rockshelters archaeologists have excavated a rich record of hunting and gathering lifeways that began around 13,000 years ago and endured until European contact. Above the deposits, painted along rough limestone walls, is a rich record of mural art that began around 1700 BCE and remained in production for more than 3,000 years.

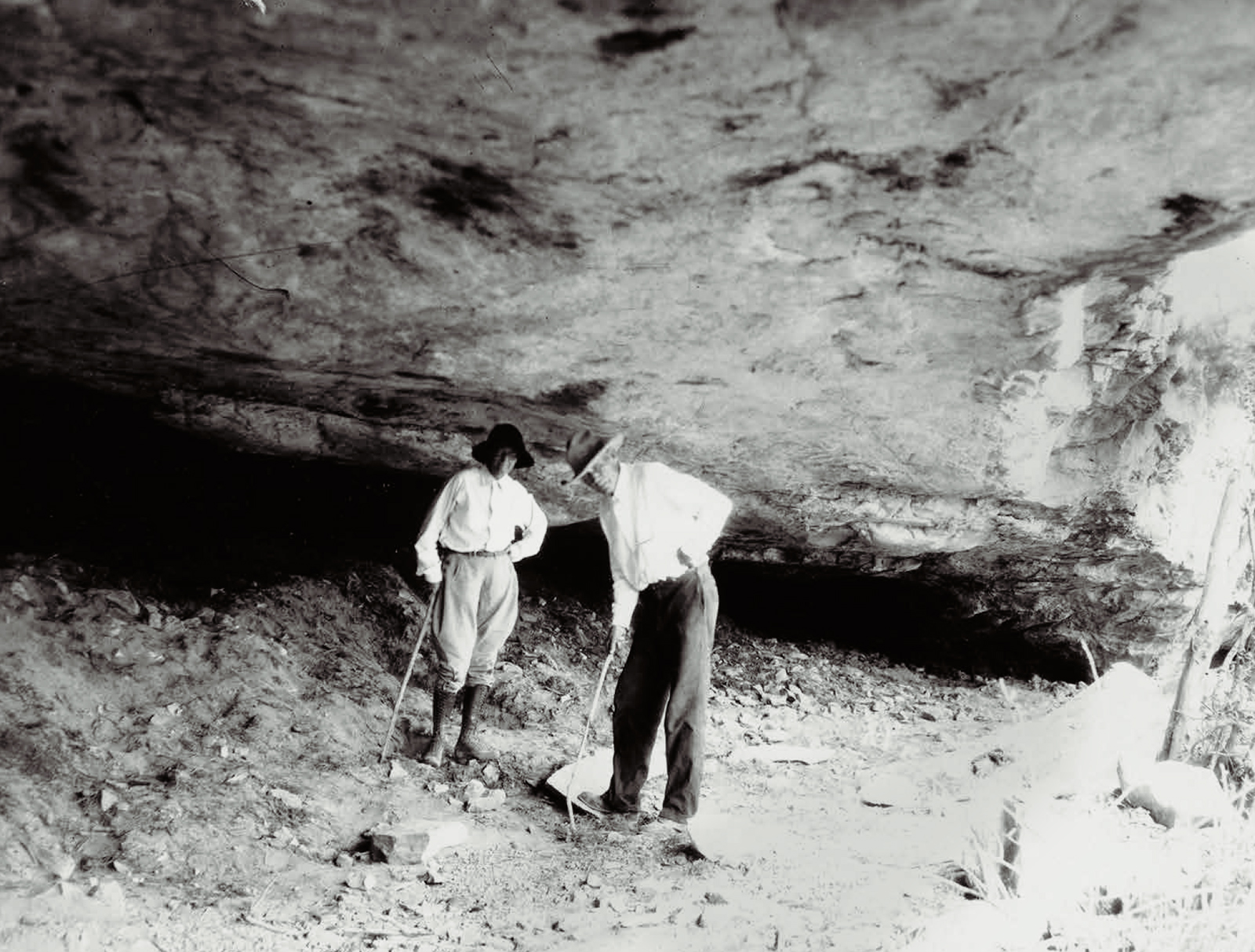

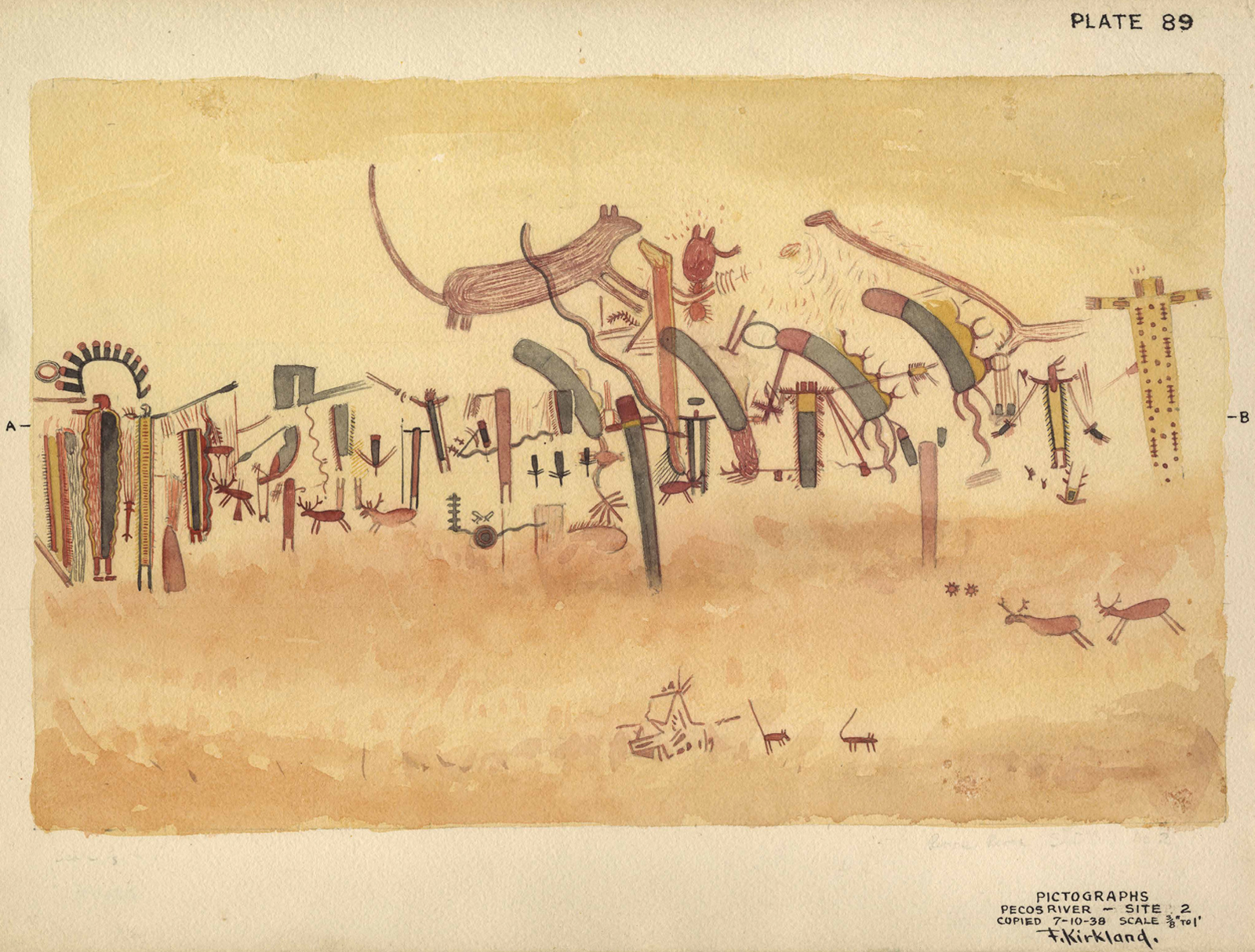

THE MURALS

Archaeologists have reported more than 300 prehistoric murals in the region. New rock art sites are discovered every year. The murals range considerably in size and complexity. Some are small, less than a meter in length and height, and have only a few figures. Others hold thousands of figures and are as much as 150 meters long and 15 meters high. While some may see these as a random collection of images painted over long periods of time, trained artists have shown that many of the murals are planned compositions.

VIRGINIA CARSON

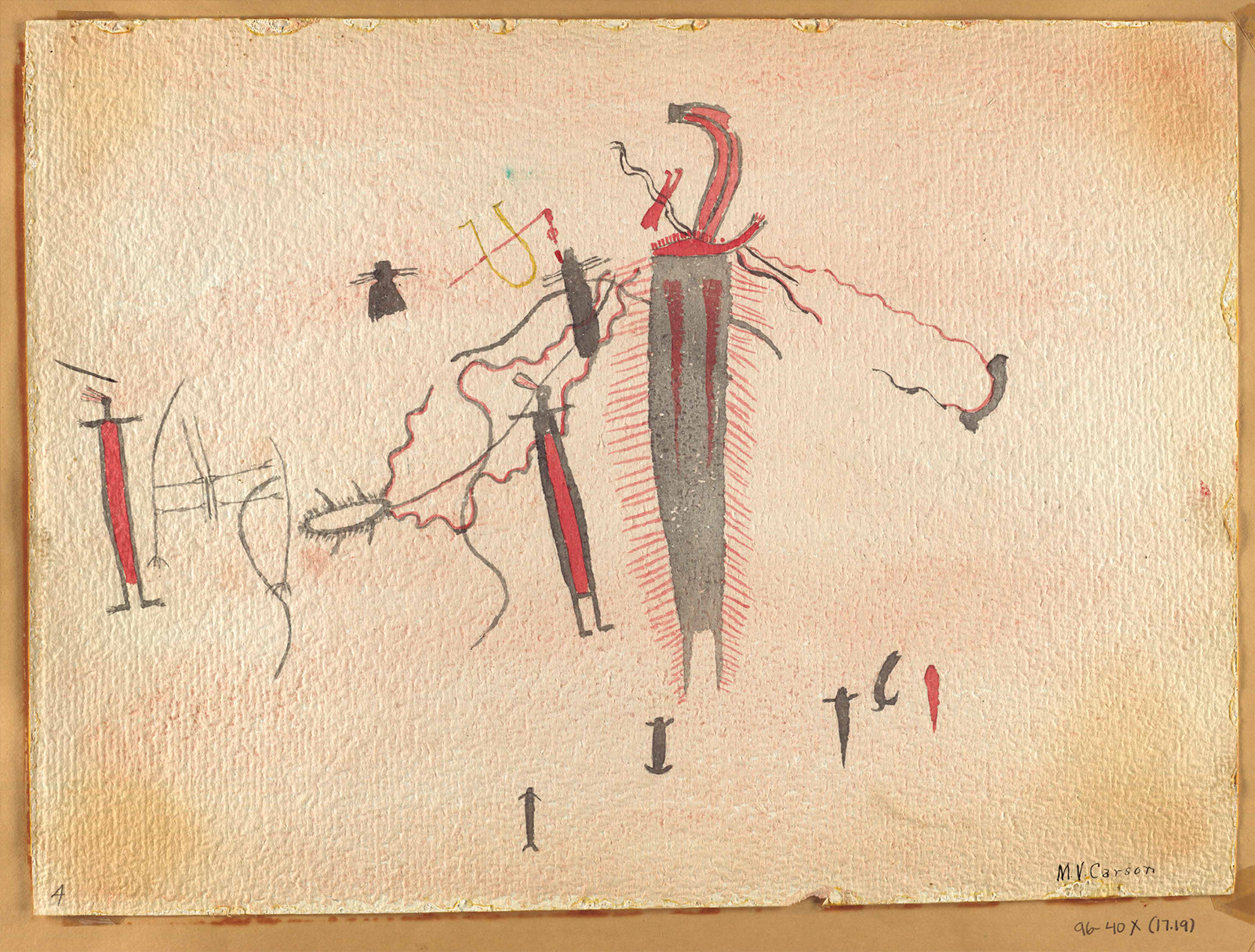

In 1931 artist Virginia Carson took part in an archaeological expedition sent to the Lower Pecos by the Witte Museum of San Antonio, Texas to produce artistic reproductions of the pictographs. She describes the murals as masterpieces of beautifully proportioned and arranged images.

FORREST KIRKLAND

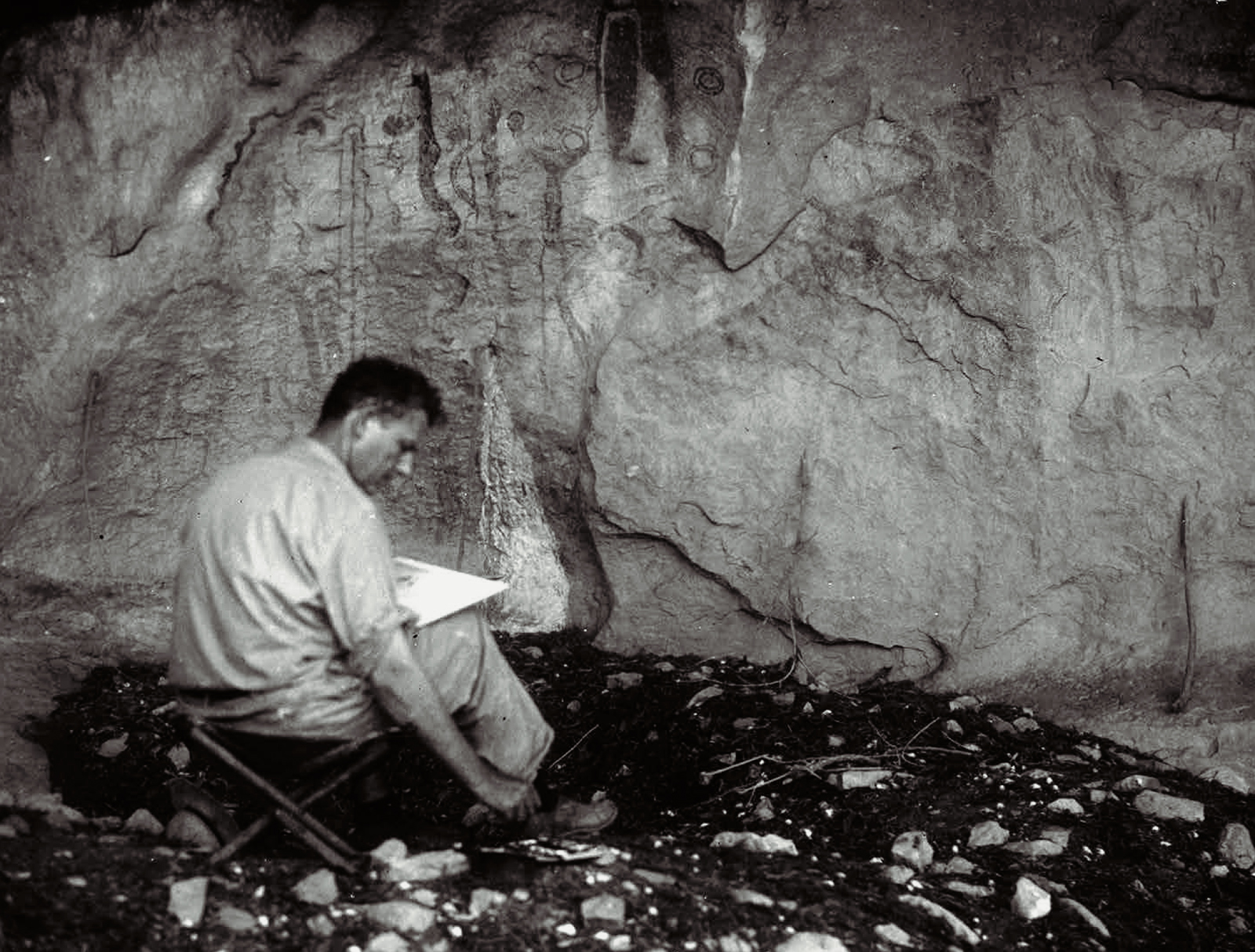

In 1933, professional draftsman and artist Forrest Kirkland produced dozens of watercolor renderings of the murals. He also supplied the first formal analysis of the paintings, including a discussion of color harmony, picture arrangement, rhythm, movement, and action. Like Virginia Carson, Kirkland recognized the murals as complex compositions. He said that moving a single figure or symbol would upset their delicate balance and detract from their artistic merit.

CAROLYN BOYD

In 1991, artist turned archaeologist Carolyn Boyd began documenting and studying the rock art of the Lower Pecos. As a trained muralist, she recognized the skill and planning needed to produce the large, complex compositions. Her investigations into the use of color and the technical history of these artworks are challenging preconceptions about hunter-gatherer complexity and the function of art in Indigenous America. Boyd’s groundbreaking interpretive work is finding parallels between the cosmological concepts portrayed in the visual narratives and the myths and histories of later Mesoamerican agricultural societies. Her research suggests ancient origins of complex concepts and rituals still practiced today.

THE IMAGERY

Artists arranged the imagery into complex visual narratives to document myths and rituals associated with the creation and maintenance of the world and the cosmos. They used graphic symbols to represent divine and mortal beings, things, places, sensations, and experiences.

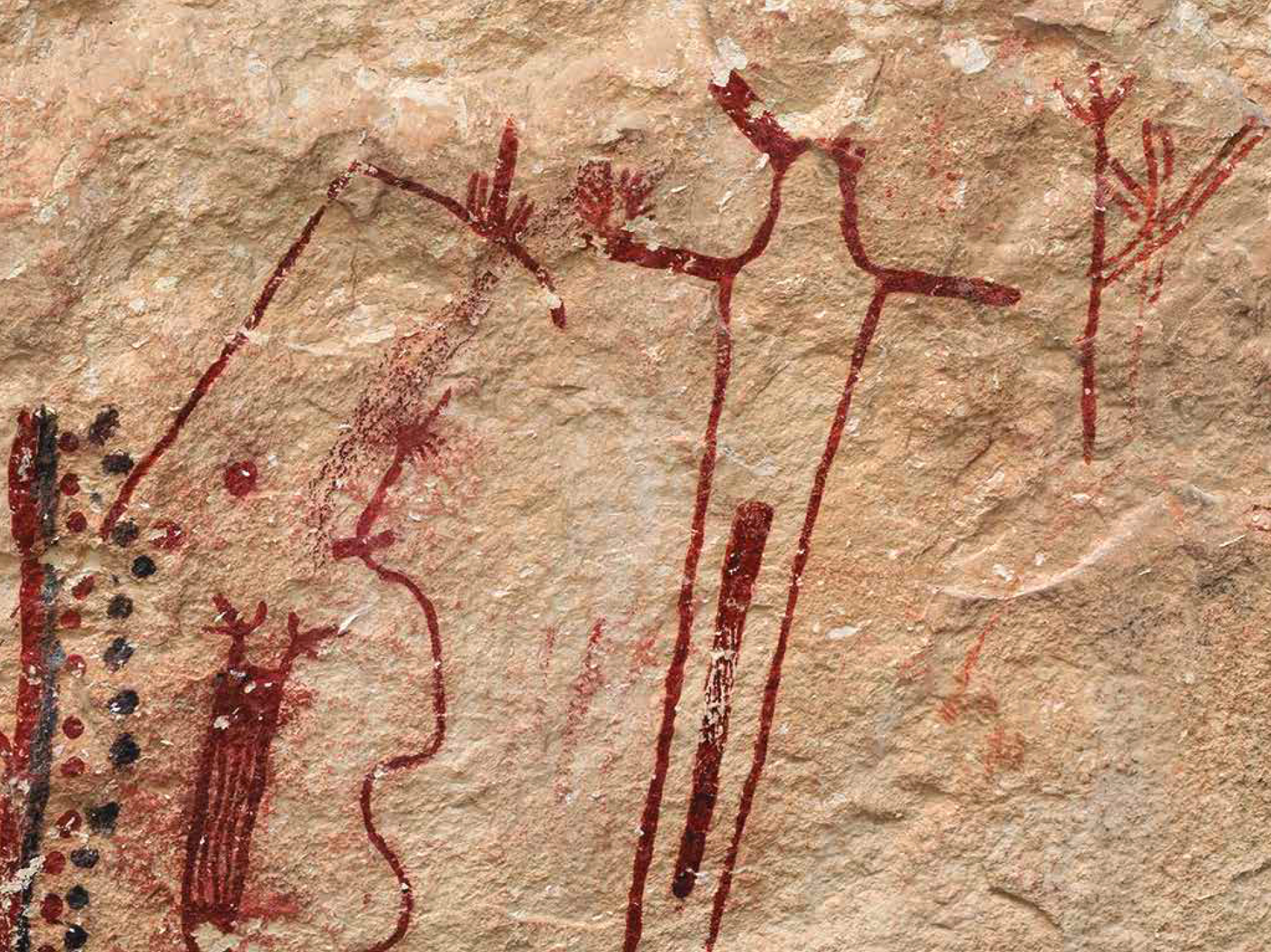

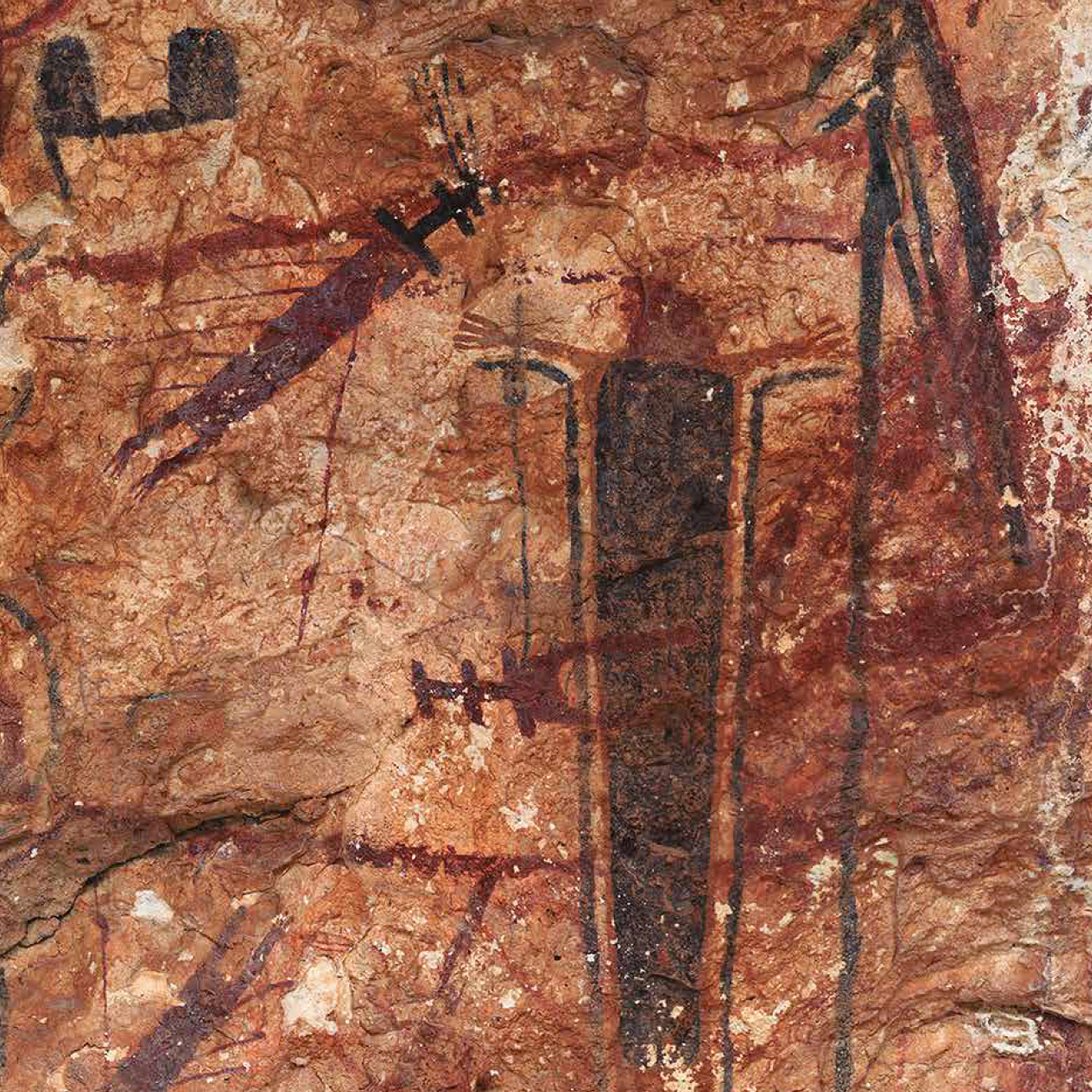

ANTHROPOMORPHSAnthropomorphic or humanlike figures dominate the paintings both in number and meaning. Most range in size between 1 m to 1.5 m, however, some are monumental, towering more than 6 m in height. Others are pocket-sized, standing no more than 10 cm. These finely executed human-like figures are often an elaborate combination of physical attributes, such as color, shape, body adornments, paraphernalia, and weaponry.

ZOOMORPHS

The most common animals portrayed in the murals are deer, felines, and snake-like figures. Birds and insects are also widespread, but smaller in size and usually surrounding anthropomorphic figures.

ENIGMATIC FIGURES

Other figures lack characteristics of either anthropomorphs or zoomorphs. These enigmatic figures range significantly in size, shape, and complexity. Sometimes they vaguely resemble plants, other times they are amorphous shapes having no analog in the physical world.

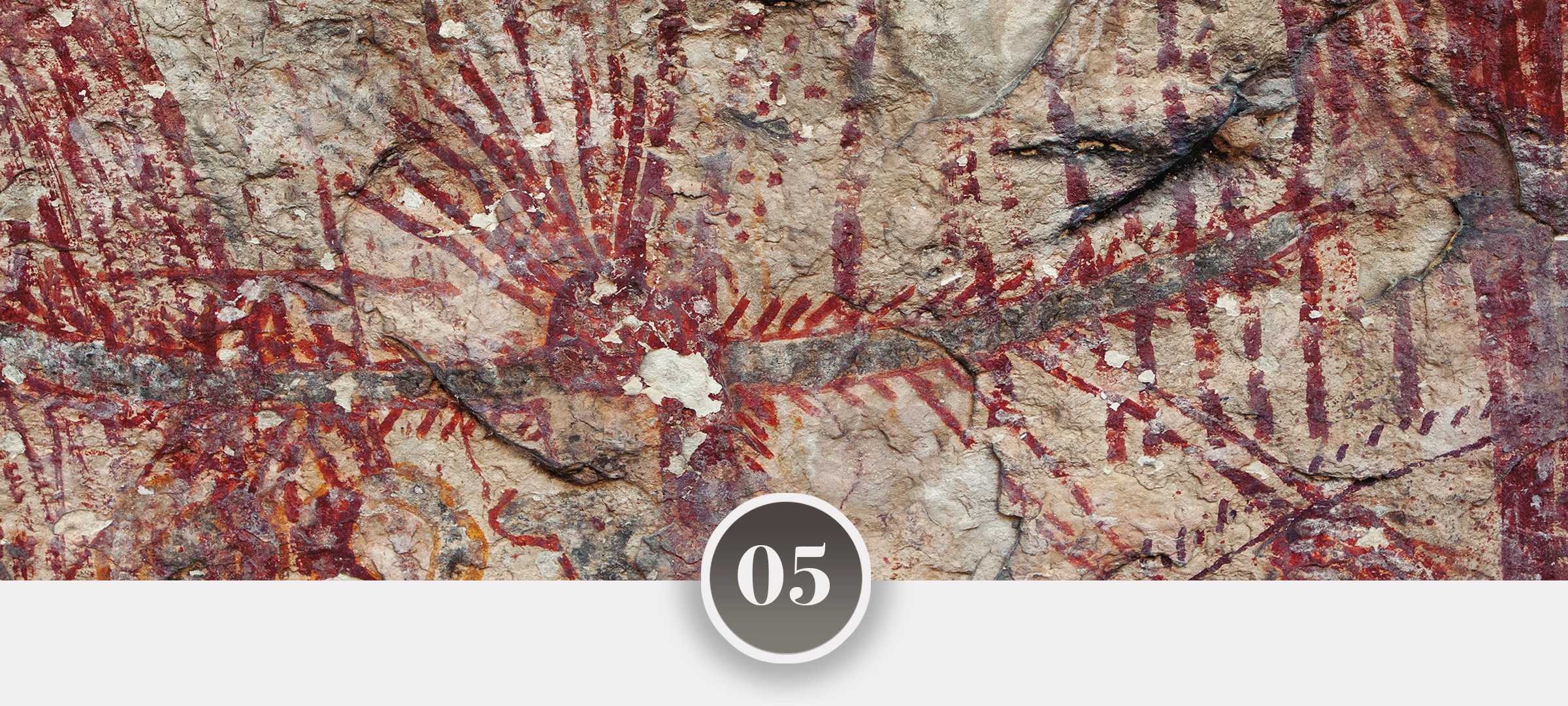

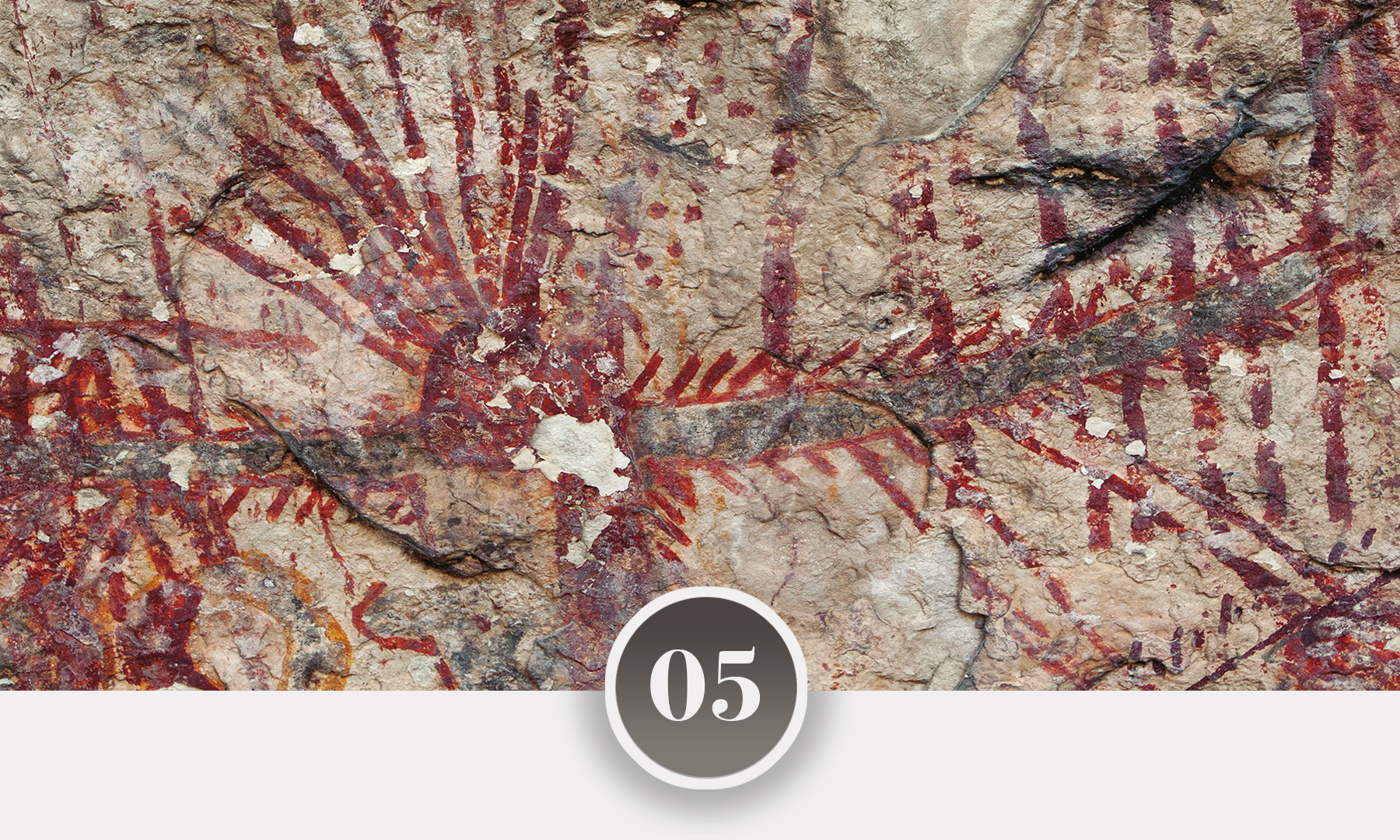

Researchers have found that the color-producing agents in the paint are mineral pigments, including ochres and manganese. Ethnographic texts and experimental archaeology suggest that deer tallow or marrow likely served as a binder and that saponins from yucca, also known as “soap root” (Yucca spp.) mixed with water served as an emulsifier. Each ingredient in the paint was sacred and a source of power that gave life to the images.

TOOLS OF THE ARTIST

Perched on ladders or scaffolding, artists used pigment crayons to sketch out complex compositions. They applied the paint with brushes made from fiber, animal hair, and feathers, and used other tools such as straight-edges and stencils. With skilled and intentional brushstrokes, artists deftly painted murals on rough limestone canvases arching several meters overhead. The precision and clarity of lines found in the paintings would present a significant challenge for even the most skilled artist.

SIGNIFICANCE

The care with which artists selected ingredients and created the art suggests that their goal was to produce exceptional art. Not for the sake of art, but for the sake of life. Native American peoples perceived a universe in which a life force imbues all things, including rock art and its stone canvas. In this view of reality, characters in the rock art are living beings that have their own point of view and intentionality.

Colors are loaded with potency and symbolism. They are associated with specific deities, spirit beings, natural phenomena, gender, emotions, souls, and the cardinal directions. Some Native Americans even perceive colors as words and magical songs of the gods. The artists’ choice and application of color transformed and enlivened the images.

ATTRIBUTES

Human and animal forms supplied a framework upon which artists added physical attributes to name characters in the stories told through the art. Colors, body adornments, headdresses, weaponry, and even the number of fingers and toes functioned like a graphic vocabulary that conveyed meaning. Think, for example, about the attributes of Medusa from Greek mythology or Thor from Scandinavia. We recognize them by their distinctive attributes-hissing snakes as hair and a mighty hammer.

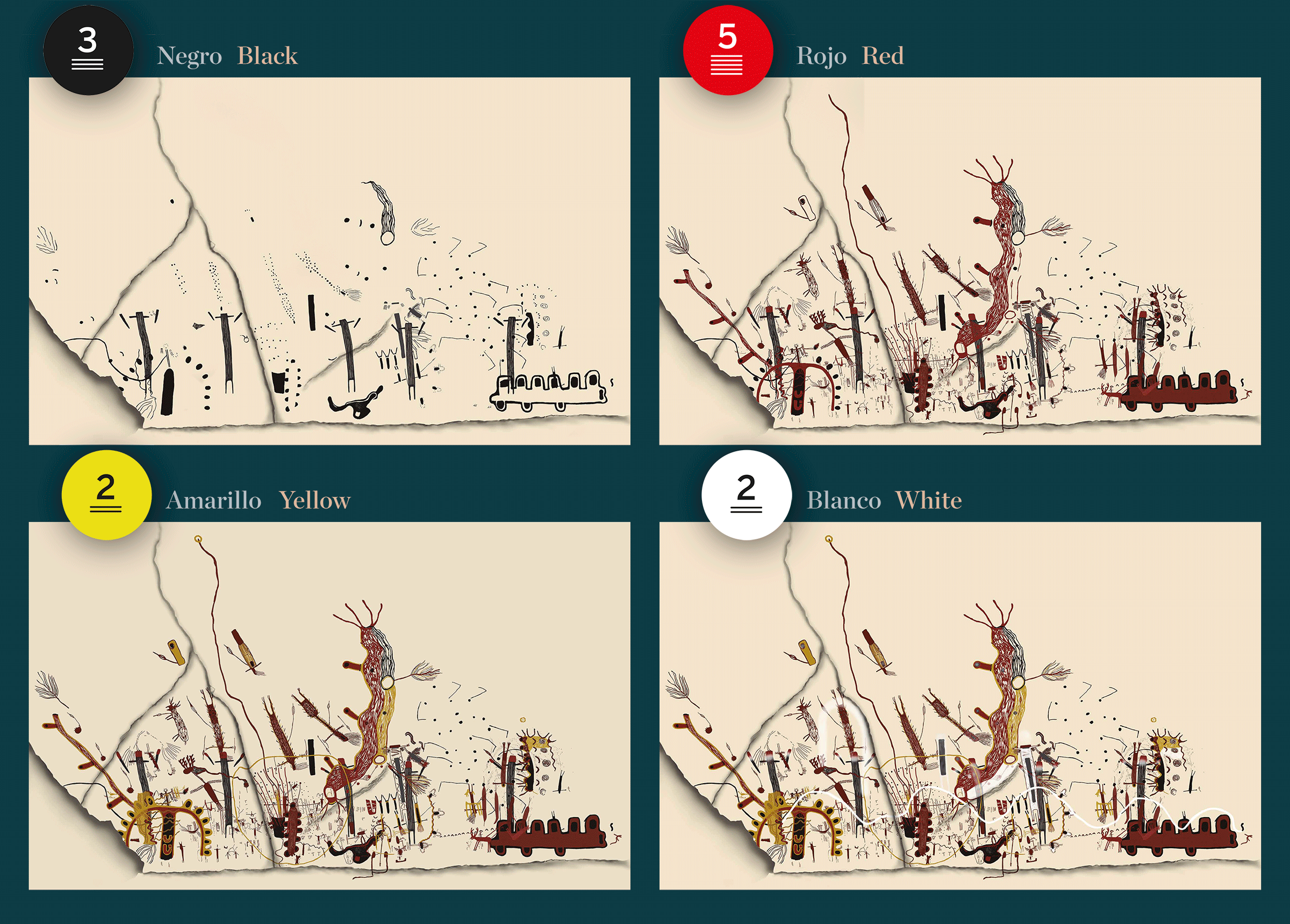

PAINT SEQUENCE

The murals’ painting sequence reveals that they are well-ordered and carefully planned. Using a handheld digital microscope, researchers have discovered that many Lower Pecos artists followed a strict paint application order when creating the murals. They applied black paint first, followed by red, then yellow, and finally white. As a result, elements of one figure are painted over and under elements of another figure, weaving them together to form a complex composition.

BRUSHSTROKE

Everything carries meaning – the ingredients in paint, the order of paint application, attributes, and even the choice of brushstroke. For example, artists often portrayed figures with lines entering or coming out of open mouths. These lines stand for sound in the form of speech or song, and they represent breath or the sense of smell. To differentiate between inhalations and exhalations artists altered the direction of the brushstroke.

VISUAL CREATION NARRATIVE

Carolyn Boyd found patterns in the mural that relate to the myths and rituals of Aztec and Huichol peoples in Mexico. These patterns led her to interpret the panel as a pictorial creation narrative. The imagery relates the sun’s daily cycle and its apparent path along the ecliptic throughout the year. It documents the changing seasons and the beginning and ending of ages and the mythic pilgrimage and sacrifice that gave birth to the sun and time.

CYCLES OF TIME AND MEANING

Through the careful application of colors laden with meaning and agency, the artists wove cycles of time into the mural.

- The artist began with black, the color of femininity, the underworld, and primordial time, a time of perpetual darkness.

- After the black paint dried, the artist applied red, the color associated with masculinity, fire, and blood. It is the fiery red glow appearing on the horizon just before sunrise. The union of red and black, masculine and feminine, initiated creation and gave birth to the sun.

- The next color applied was yellow, the color associated with the warm rays of the morning sun as it overcomes the cold black of night and the red of predawn.

- And finally, the artist applied white, the color associated with the light of midday. It is the color of sacrificial transformation and transcendence, and the return to primordial time. Thus, the cycle of life continues.

Subdirección General de Museos Estatales | Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte

Carolyn Boyd Texas State University | Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center

Pilar Fatás | Museo de Altamira

Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center Comstock, Texas

Texas Archeological Research Laboratory University of Texas, Austin

Witte Museum San Antonio, Texas

Ancient Southwest Texas Project

Jerod Roberts

Chester Leeds

Carolyn Boyd

Nexo

Texas State University San Marcos, Texas

Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center Comstock, Texas

Texas Archeological Research Laboratory University of Texas, Austin

Witte Museum San Antonio, Texas

Phil Dering, Jessica Hamlin, Vicky Roberts, Audrey Lindsay, Tim Murphy

Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center

Jerod Roberts Texas State University

Marybeth Tomka Texas Archeological Research Laboratory

Amy Fulkerson, Leslie Ochoa, Harry Shafer and Marise McDermott

Witte Museum

Bob Scribner Texas A&M University-Galveston.

This exhibition is the result of the collaboration in the framework of the Rock Art Network, formed by the Getty Conservation Institute and the Bradshaw Foundation.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation