Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Rock art images are historical data in their own right – forming an archive that far pre-dates written texts in many regions, and far outstrips other forms of material culture in terms of potential to interpret past ontologies. Just as one learns to read text, though, the language of rock art requires an understanding of emic – inside – knowledge (whether direct or by analogy) to be truly fathomed. Knowing when images were made, however, is crucial in application to culture contact and its ramifications. Although some direct radiometric dates are starting to appear in southern Africa, it arguably makes more sense to rely on images that demonstrate contact unequivocally – cattle, sheep, horses, guns – than to speculate on an undated corpus of wild animals and human figures that runs to many thousands of years prior. Not only this but it becomes increasingly clear that essentialist tropes of San from the ethnographic present didn’t obtain in the colonial contact era, if ever they held at all. Mixed authorship, it transpires, requires alternative readings and this offering chronicles just some of the attempts to achieve better ways of applying rock art data to the past of Indigenous southern Africans.

A decade ago Ben Smith (2010) published his take on the collective efforts of rock art researchers to perceive the passage of time in hunter-gatherer rock art, Envisioning San history. Now, and in this volume dedicated to the history of rock art research, it seems apposite to review those efforts in the light of the scholarship that has followed – much of it stemming from the issues he problematised, as well as the answers offered to some of the long-standing questions he synthesised. In short, it is the story of archaeologists trying to put the San back into a history from which they had been effectively removed. Aron Mazel’s history (1992) of how the San were perceived by colonists and early historians charts exactly this: the reasons given for their having been written out of the record or, at best, romanticised as harmless, mystical ecologists frozen in time (cf. Lewis- Williams et al. 1993; Mazel 1992: 765; Wright 1978). This is a selective account of the scholarly efforts to use archaeology, and rock art in particular, to redress those errors.

The first part reviews the endeavours to find, in the rock art of ‘traditional’ appearance, evidence for change through time owing to contact between autochthonous hunter-gatherer artists and incoming African pastoralists, African Farmers and European colonists. The second part reviews the endeavours to chart said contact and change in bodies of rock art that display ‘foreign’ introductions – the diagnostic ‘contact’ images.

Working from the position that paintings and engravings made by the San and other rock art producers involved in the entanglements of the last two millennia of contact engage in some way with those entanglements, they constitute an Indigenous archive – one that enhances and contests other sources. This is especially pertinent to the colonial era whose written documents (whether original material or subsequent readings) weigh so heavily in the balance of evidence. Rock art, it has been argued, provides a reverse gaze (Ouzman 2003). It speaks to us across the centuries from the perspective of its makers, and there is a history of research into its decipherment.

Reading rock art, writing history, Thomas Dowson’s 1994 breakthrough piece asserting that images have the potential to exhibit change through time, and why, is precisely this – an exercise in trying to make the archive speak. It was a positive stroke in a back-and-forth debate with Aron Mazel, the pre-eminent Later Stone Age archaeologist of Kwazulu-Natal. The debate has been rehearsed elsewhere (e.g. Blundell 2004; Mitchell 2002; Smith 2010), yet it deserves a precis here in order to set the scene for its inception and subsequent unravelling – with some observations that have escaped most critical treatments.

One only has to read the commentary in Lewis- Williams’ 1982 submission to Current Anthropology to see just how ground-breaking it was to apply any theory at all to San paintings, let alone one that dealt with the meaning of so many facets of rock art. A short time after Lewis-Williams’s exposition of the use of materialist theory his student, Colin Campbell (1986, 1987), took up the challenge and applied it to images that (importantly for our purposes here) clearly pertained to contact – contact between foragers and farmers, and contact between foragers and colonists. His remains one of the best-worked applications of theory to the material culture record and is subsequently much- cited. However, it is not without flaw and, as we shall see, makes errors in assigning authorship which sowed the seeds of confusion concerning key rock art sites. Crucially, though, Campbell was able to show that contact, for the San, was negotiated in their paintings on their own terms and in their own spiritual idiom thus, even when a cattle raid panel appears ‘narrative’ at first glance, for the authors it performed all sorts of ‘functions’ (sensu Lewis-Williams 1982) within San society (Campbell 1987: 124). Campbell (1987: 133) saw the San ‘not as victims of immutable processes but as active participants in the changing circumstances of the contact period’.

Publishing his thesis in the Natal Museum Journal of Humanities, Mazel ‘s People making history (1989a) set out a position that he could discern, from eight rock shelter excavations, the history of Thukela Basin hunter-gatherers from 10,000 BP to AD 1800. This was refined in a more specific article (Mazel 1989b) in which he claimed to be able to see something of the Changing social relations of this region, though from 7000 to 2000 BP. Acknowledging the intellectual lead taken by David Lewis-Williams in the first half of that decade (Lewis- Williams 1982, 1983, 1984), Mazel (1989a: 25) argued for a shift in emphasis away from the environmentally deterministic New Archaeology of the 1960s and ‘70s – instead of asking people-to-nature questions, we should ask people-to-people questions – in favour of a more social archaeology.

Adopting an historical materialist approach, Mazel adduced excavated evidence for aggregation and dispersal phase sites – in much the same way, and at the same time, as Lyn Wadley had in her hypothesis (1987, 1989, 1996). Both Mazel and Wadley saw the frequency of certain types of artefact as evidence for either the aggregation or the dispersal phases of hunter-gatherer life in the Later Stone Age. Of special significance were ostrich eggshell (OES) beads and arrow armatures (linkshafts) which they interpreted in the light of Kalahari Ju|’hoan San ethnography as items associated not just with everyday use, but as gifts exchanged between kin to cement delayed reciprocity networks. A good knife given today, for example, could ensure access to resources in a consanguineal relative’s camp next year, should adverse circumstances demand (Guenther 1999: 28). Extra-kin relationships known among the Ju|’hoansi as hxaro (e.g. Weissner 1998) and among the Nharo as ||ai-ku (Guenther 1986) cultivated over a person’s lifetime can carry such reciprocity beyond even one’s neighbouring camps, radiating along networks of paths that extend hundreds of kilometres (Guenther 1999: 28). Ostrich eggshell beads and other items given in gift exchange, therefore, when found in abundance were proof positive of large gatherings where family and exchange partners would meet and engage in social activities – visible in the material culture record (Mazel 1989a, 1989b; Wadley e.g. 1989). Kalahari San life is organised around such seasonal aggregations in which family bands come together to hunt, and feast; manufacture clothing, adornments and tools; exchange news, stories and dreams; arrange marriages and initiations; and to both exchange and perform ceremonial techniques such as dancing (for negotiating with the spirits of animals and humans, healing and rainmaking) and, crucially for groups outside the Kalahari, making rock art (Guenther 1999: 25). Both Patricia Vinnicombe (1976) and Patrick Carter (1978) had hypothesised that some groups of San migrated from all over the southern African lowlands into the highlands of the Maloti-Drakensberg in order to pursue the summer aggregation of large game and to aggregate themselves for the aforementioned reasons. The high-altitude paintings were made seasonally and, according to Lewis-Williams original hypothesis (1981) reflected all of these concerns.

Furthermore, Mazel and Wadley saw gender relations playing out in their respective research areas. Wadley (1989: 43–45) determined formal seating positions for men’s and women’s artefact production areas within the communal occupation, across time, at Jubilee Shelter in the Magaliesberg. Mazel (1989b) saw the devaluation of the female role in hunter-gatherer society being actively challenged and redressed by women harnessing the social relations and forces of production to their own ends. Between 4000 and 2000 BP there is supposedly a visible increase in plant food exploitation, small game hunting/trapping and fishing – all associated with women. An increase in the number of adzes for the woodworking of digging sticks, and of grindstones for preparing plant foods attests (Mazel 1989b: 34–39) to an increase in the female contribution to the diet and therefore increased levels of political and economic power for women. The enterprise to reach social understandings was now up and running. Such bold steps (Mazel 1989b: 39), however, were bound to attract attention, not least from those whose data did not fit the hypothesis.

In a devastating critique of the historical materialist trend Larry Barham (1992) suggested these frontrunners be recalled. Citing his own excavations in Swaziland (eSwatini), he claimed he had found greater numbers of OES beads in rock shelters that were far too small to have been aggregation phase sites (Barham 1992). What works for rock art, he argued, doesn’t necessarily work for ‘dirt’ archaeology (Barham 1992; see also Witelson, this volume), prompting pithy reposts from both Wadley (1992) and Mazel (1993). Whatever the outcome of the debate, at least it got people to think about women (Mitchell 2002: 219) and precipitated greater focus on gender studies (e.g. Wadley 1997).

A major difficulty here is that finding ostrich eggshell beads or what we think are arrow armatures patently does not prove the presence of Ju|’hoan-like hxaro gift exchange networks... (Mitchell 2016: 412).

But finding evidence that they travelled very long distances does. Since having said this, Brian Stewart et al. (2020, including Mitchell) have gone on to show the likelihood that hxaro-like exchange networks have probably obtained, between the arid southern African interior and the wetter Lesotho Highlands, since the Middle Stone Age. Strontium isotopes on ostrich eggshell beads declare their provenance to be anywhere but the Highlands, some beads travelling 300 km distance from 33,000 years ago until the late Holocene (Stewart et al. 2020: 6457). This means it is possible for archaeology and ethnography to interdigitate, with results resonating across millennia, as long as they are substantiated with testable hypotheses – as opposed to the arbitrary application of ethnographic labels to material that bears a vague resemblance to something in the ethnographic present (d’Errico et al. 2012; Pargeter et al. 2016).

Sometimes overlooked in this debate, however, is that Dowson (1993) went on a similar offensive – for all the talk of OES beads, arrow armatures, adzes and grindstones the excavators had neglected to pay attention to those most visible artefacts: hunter-gatherer images. Mazel, himself a rock art scholar, had inexplicably left the paintings out of his history (Dowson 1993: 641). Mazel’s 1992 cataloguing of the changing light in which the San have been treated in the literature of the preceding 150 years is based on historical documents and thus a ‘value laden Western construct’ (Dowson 1993: 642) despite the fact that he makes frequent reference to his own historical materialist take on the excavated record (Mazel 1989a, 1989b). Not only this but it concludes that the San had no part to play in the making of this history during that time (Mazel 1992: 766). In a misapprehension, and therefore misrepresentation, of Mazel’s article (see Mazel 1993: 889), Dowson (1993: 641) believed that Mazel was attempting to produce a history of the Maloti- Drakensberg San from these texts, and was doing it without considering the painted record, at that.

The misrepresentation is indeed egregious, although it had unforeseen ramifications that have played out over the decades since, not least Dowson’s own attempts to construct San history with rock art, and all that this implied. In Mazel’s (1993: 889–90) response he stated that, even if he had committed the ‘host of crimes’ of which he stood accused, one still couldn’t reliably incorporate rock art in a history, since there was no chronology for it. Moreover he called Lewis- Williams’ (1993: 49) bluff that ‘...much of the art can be sufficiently dated...’ which could only then have conceivably applied to ‘contact’ images of sheep, cattle and horses (Manhire et al. 1986; Campbell 1986, 1987) and by extension, shields, spears and guns (Challis 2012 inter alia; Sinclair-Thomson 2016, 2019). As we shall see, absolute dates recently obtained by Adelphine Bonneau and colleagues (e.g. Bonneau et al. 2017) have significantly altered the situation. In the early ‘90s, though, Mazel had a point: the rock art of the traditional corpus was dateless, and though he recognised the rock art as containing, somehow, the history of its producers, this would remain opaque, he said, until it could be well ordered (Mazel 1993: 891).

The perceived problem here was, and still is, that because the rock art of the traditional corpus and its widely-accepted interpretations were suspended in the ethnographic present, their findings could not be projected far back in time. How can you know what you’re looking at if you don’t know when it was made? The allegations of ahistoricity in the shamanistic approach had prompted Lewis-Williams’ (1993: 49) reaction to the ‘incorrigible chronophiles’ so obsessed with determining when things had taken place, as opposed to how or why. It is the processes at play in society that one can see unfolding in rock art, that matter (Lewis-Williams 1982, 1995, 1998). Indeed Dowson (1993: 642) called for nothing less than a new concept of history, one:

...that breaks from emphasising a chronology of only certain kinds of events, one which accepts other evidence and other kinds of statements and constructions.

The difference was that Dowson (1993: 642) thought it could be done, and that rock art could offer far better insights than mere ‘occupational debris’. Where Mazel (1993: 891; 2013: 50) had found no way to weave rock art into his historical materialist narrative, and Barham (1992) had pulled everyone up short for reading too much into their artefacts in this manner, Dowson believed that historical materialism rendered San history perceptible. Hot on the heels of the debate with Mazel, Dowson (1994) proposed a relative sequence that could, he said, be seen across much of the Maloti- Drakensberg (quite apart from the relative sequences suggested by those who had employed Harris matrices, Russell 2000, 2012; Swart 2004; cf. Mazel 2009, 2013, though see also Pearce 2010). Owing much to Campbell’s (1987) historical materialist approach, Dowson’s structurationist sequence could be discerned among the images of the traditional corpus of rock art. First, however, one had to believe that Maloti-Drakensberg San responded to contact with newcomers the way that Mathias Guenther (1975) had observed the Kalahari Nharo and other ‘Farm Bushmen’ responding in the twentieth century (Dowson 1994, 337). San healers had become more ‘professional’ owing to the complex of new illnesses and new treatments they had to master, their subsequent high demand brought high esteem (Guenther 1975: 163):

The following qualities of a dancer of renown account for his social importance: he possesses a great amount of ritual, esoteric knowledge; he is wealthy; he is independent of Europeans or Bantu [-speaking] people; he is accorded high prestige and enjoys charismatic appeal.

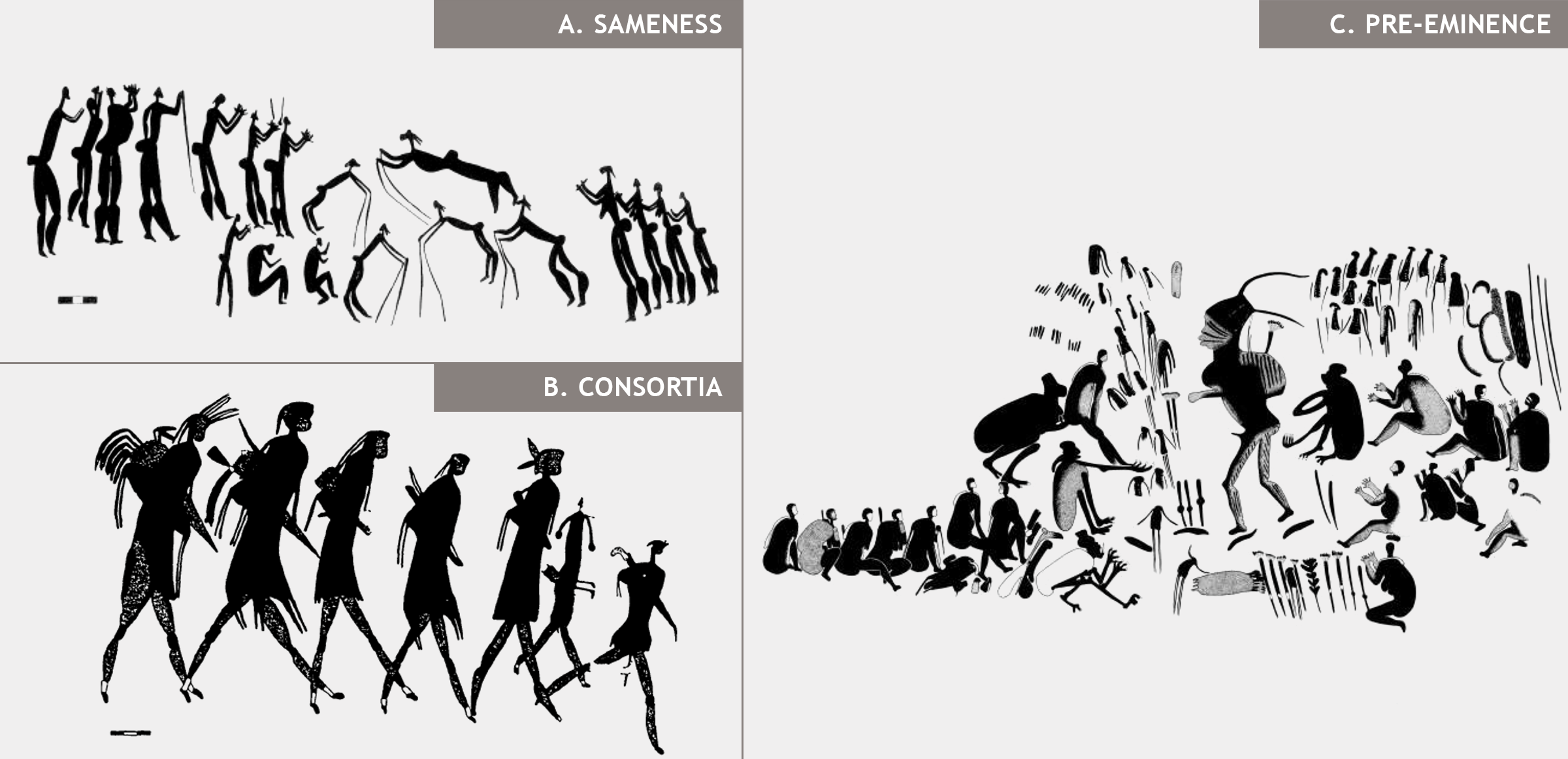

Contact, it transpired, produced conditions ideally suited to an historical materialist interpretation because, if erstwhile egalitarian bands had to elect leaders, or produce goods and services for which they might accrue wealth or kudos, one had the makings of a proto-hierarchy with the ‘eventual domination’ (Campbell 1987: 128) of San society by shamans. In Dowson’s structurationist reading one could see this happening, from one site to the next, quite literally in the aggrandisement of human figures: small becoming large, simple becoming elaborate, a focus on groups (communal then consortia) changing to a focus on individuals (‘pre-eminent’ shamans, Dowson 1994: 335– 340; Figure 9.1).

In his 1975 The Trance Dancer as an Agent of Social Change, Guenther had observed that the San chose leaders:

...to deal with Government on behalf of all of the Bushmen of the District. When the Bushmen on the farms discuss this last issue and debate who could be a suitable headman for the Ghanzi Bushmen, it is often the consensus that this should be one of the great dancers.

In Dowson’s (1994) application of this concept to the rock art, Guenther’s ‘dancers of renown’ became ‘pre- eminent shamans’, displaying, as Campbell (1987) had put it, their symbolic labour for their own and farmer communities to see. They rose to prominence, dealing with spirits-of-the-dead and sicknesses of all sorts, and they became distinguished in the south of the Maloti-Drakensberg – the region where forager/farmer interaction is asserted to have been most protracted (Dowson 1994: 334).

As befits the model set out by Campbell that rainmakers would have accrued primitive capital (Marx 1867) in cattle, and so formed the beginnings of a class system, Dowson mentions that rainmaking would have been mutually intelligible between hunters and farmers (evidence for which is compelling in the in the Maloti- Drakensberg rock art, Dowson 1998). Farmers would have to have understood San rainmaking in order for this contract to work. Interestingly, however, Guenther’s observation that San healers acquired new medicinal knowledge to deal with farmer illnesses – such as witchcraft in the African Bantu-speakers’ cosmology – is not mentioned by Dowson. As we shall see in the second section, the incorporation of farmer beliefs and subsequent syncretism appears to have been very much a part of the culturally creolizing groups of the nineteenth-century Maloti-Drakensberg.

Such selectivity is prerequisite for an interpretive paradigm which requires that rock art remain ‘traditional’ in appearance for at least some time after contact. The most convincing case so far made for this being the aforementioned rainmaking evidence, in which rain animals appear in rock art that exhibits more and more recent features.

Of the many questions one might raise in response to this hypothesis, one that has not yet been highlighted is why the pre-eminent shamans should wish to communicate such self-promotion in paint (even if they had been elected). Strong healing powers are one thing, kudos another, but Guenther himself states (1999: 34) that leadership is only ever taken up with great reluctance: ‘...the position of headman...has not become institutionalised within society. It holds no rewards...’. In fact leadership of the sort hierarchical societies might recognise is ‘unheard of ’ (Barnard 1992: 108; cf. Silberbauer 1982), indeed ‘“all you get is the blame if things go wrong”’ (Marshall 1976: 195).

Unfortunately, Dowson’s view assumes leadership is desirable or innate – somethings that goes against the grain of Lewis-Williams (1982) original diatribe contra the innatist approaches. It follows the assumption that hierarchies will inevitably form, which suits the historical materialist, and in this instance, the structurationist approaches. More likely would be the propensity for San to attribute to the ‘dancer of renown’, acknowledgement of expertise in that specific theatre, whether they be a particularly adept healer, rainmaker or ‘tamer’ of animals – an explanation from within the San idiom that has been more recently proposed (McGranaghan and Challis 2016) – the audience assessing the individual in terms of their performance, and in the performance of the painting itself (Lewis-Williams 1995; cf. Witelson 2019).

And yet leadership does emerge. At least, there are named leaders of multi-ethnic and creolised ‘Bushman’ bands in the nineteenth-century Maloti-Drakensberg; Nqabayo, Mdwebo, Madolo, Mbelekwana, Mjinga, Hans Lochenberg and Soai (Blundell 2004; Challis 2008 inter alia; Jolly 1996b, 2006; Mallen 2008; Mitchell 2010; Vinnicombe 1976; Wright 1971). In the nineteenth century, people would cleave to charismatic individuals – those with whom they saw their interests, and lives, best protected (Etherington 2001). There is little evidence, however for hierarchies (Challis 2008: 253– 257; 2016: 296). Moreover, the hypothetical sequence towards power and prestige, from egalitarian group, through consortia to pre-eminence is undated (Mitchell 2002: 407; Smith 2010: 348–349) and may flow in reverse order for all we know (Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022).

‘The death of the postcranial body’ marked what Blundell saw as the increased importance of facial features for post-contact ritual specialists. Image courtesy South African Rock Art Digital Archive, www.sarada.co.za. 2b Figures of comparable size almost identical to the ‘pre-eminent Shaman’ at Dowson’s type-site (compare with figure 1c). Image courtesy Alice Mullen.

In a phenomenological reworking of Dowson’s model, Geoff Blundell (2004) took the pre-eminent shamans for ‘Significantly Differentiated Figures’ – highlighting the attention paid to painting their faces and accoutrements while their bodies diminish in both size and significance – the embodiment of the rise to prominence of these ritual specialists, and the focus on the individual. Taking for his cue the leaders of the nineteenth-century region in which a particular concentration of such images are found, he saw the faces belonging to the nineteenth century, or to the centuries of contact preceding it, when in fact there are no dates to match. Not only this but systematic survey beyond the confines of this vicinity have yielded more Significantly Differentiated Figures across the southern Drakensberg and the Maloti of Lesotho (Challis et al. 2015; Challis 2018). While this might not pose a problem to the hypothesis per se, the discovery of figures virtually identical to that at Dowson’s type-site all painted large, elaborated and clustered together in a group, does (Mullen 2018: Figure 9.2).

It would be nice to think that changes owing to contact were observable within the traditional corpus, especially since evidence for cultural borrowing is attested at increasingly early dates – residues on pottery at Likoaeng and Sehonghong in the Lesotho Highlands have recently yielded evidence of dairying by hunter-gatherers at c.1000 cal BP (Fewlass et al. 2020). The ‘shaded polychromes’ that San rock art is famous for may well have continued throughout contact and into the historical era, although there is no evidence it did (Mullen 2018). White paint, moreover, is not an indication of age as has been argued, since different white pigments age differently (Mullen 2020). Carbon black in paint samples from shaded polychrome eland at sites with SDFs has returned radiometric dates well over 2000 years, thus placing those particular specimens out of reach of any contact (e.g. Bonneau et al. 2017; cf. Mullen 2018: 69–78). The chief difficulty with the pre-eminent or significantly-differentiated shaman argument is (until absolute dates are secured) that it is not applied to any demonstrable contact images.

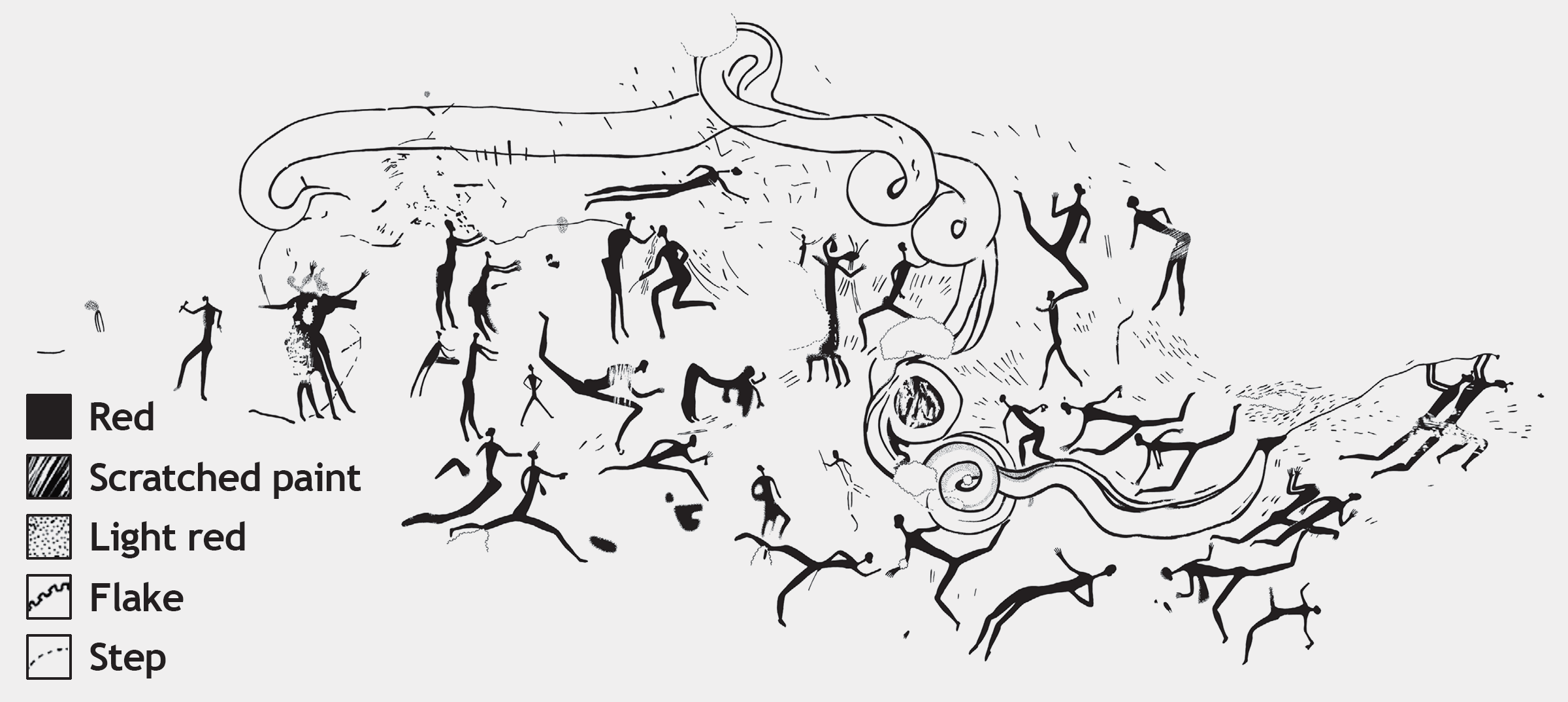

After Campbell 1987, people wearing brimmed hats float next to trance-related horse images with fringed streamer tails.

The problem for many scholars, it seems, is that the foreign material culture which defines the rock art of the contact period – shields, spears, then horses and guns – engenders essentialist tropes. Fat tailed sheep, for some, meant that Khoe herders must have been nearby (e.g. Cooke 1965) as opposed to their being an indication of pastoralism itself. The logical explanation, it seemed, for cattle images in the Maloti-Drakensberg, was that they had been seen by San and ‘recorded’ in their parietal diaries. At best, cattle and horses might be afforded the status of those stolen by the hunters for food, and ‘logged’ in the paintings as such (Willcox 1963: plate 36 op.83; Lee and Woodhouse 1970: 153). Worse assumptions prevailed over the colonial era images, such that ‘man on horse with hat’ or ‘man with gun’ were Europeans; Boers or British soldiers (e.g. Vinnicombe 1976: fig. 15a; Campbell 1987: 116; Dowson 1993: 643; 2007: 54) even when, as Campbell himself pointed out, the hat-wearers were themselves trancing (Figure 9.3).

Two further problems are corollaries of this: first, that the artists are imagined to conform to conventionalised ethnic categories, the results of contact translated in terms of the reinforcement of such bounded entities and their stereotypes. Particularly that San, forced into the margins, kept themselves apart when quite the reverse is more evident (Mazel 1989a, 1989b; Thorp 1997; Forssman 2014, 2017). Second, that the results of contact in the form of miscegenation go unresolved in the face of evidence in the archive which speaks of hybridisation in mixed-, multi-ethnic and ethnogenetic group formations (Blundell 2004; Challis 2014, 2016; Henry 2010; Ouzman 2005; Mallen 2008; Wright 2007).

This seems to have been the case in the observations of Pieter Jolly, whose Master’s dissertation Strangers to Brothers (1994) focuses on cultural mixing and intermarriage. Establishing an impressive body of evidence for ‘symbiosis’ between the San and their African farmer neighbours, with the acknowledgement that some artists might be the progeny of mixed marriages, these communities remain mutually discrete in their connection (Jolly 1995, 1996a, 1996b). In this scenario rock art images remain the product of influence – the traditional fine line art taking on features of isiNtu- speakers’ initiation and divination ceremonies.

The anthropologist David Hammond-Tooke’s response to this took shape from his own experiences working with isiNtu-speaking societies in which San beliefs were intimately integrated (Hammond-Tooke 1998, 1999). With a focus on the Nguni-speaking farmers, this drew attention in terms of the direction of influence in the opposite direction from Jolly. Anthropologically however, as one might expect, the rationale behind Hammond-Tooke’s demonstration as to how and why San religion might become mixed into that of African farmers, is complex – a variant of the San trance dance being adopted for its association with access to potency, of animals for the San but of ancestors for the Nguni; the San trickster deity |kaggen, manifesting, in part, in the Cape Nguni witch familiar, uthikoloshe (Hammond- Tooke 2002: 282). Owing to their differential occurrence from one region to the next, however, Hammond-Tooke (2002) surmises that such partially-integrated beliefs appear in variant forms and levels in different instances of interaction. In a somewhat functionalist reading: as and when needed.

A critique that might be applied to all of the aforementioned authors is that, in their attempts to re- write San history, they could be accused of not having re-read San history, for, almost every contemporary ethno-historical record attests to the mixed or hybrid nature of the ‘Bushman’ bands of the nineteenth century. This was not lost on historians Patricia Vinnicombe (e.g. 1960, 1976) and John Wright (1971) but it was not followed through to its logical conclusion where rock art authorship is concerned. Geoff Blundell (2004) detailed the ethnic constitution of the band that was the subject of his thesis – that of Nqabayo, the alleged authors of the Significantly Differentiated Figures (or some of them), yet in this reading, their multiethnicity resulted in an overdetermination (sensu Voss 2008: 37) of San-ness rather than any syncretism in their beliefs. As we shall see, however, most if not all of the demonstrably historical rock art exhibiting cattle, horses, hats and guns, displays syncretic beliefs in culturally-creolised art forms. The endeavour, then, should be to take the more salient points of the ‘direction-of-flow’ work of both Jolly and Hammond- Tooke, that is to say the great complexity of interaction, and introduce the historically-attested ethnogenetic borderland groups that are more likely to have made the images that Campbell and Jolly had cited in their evidence.

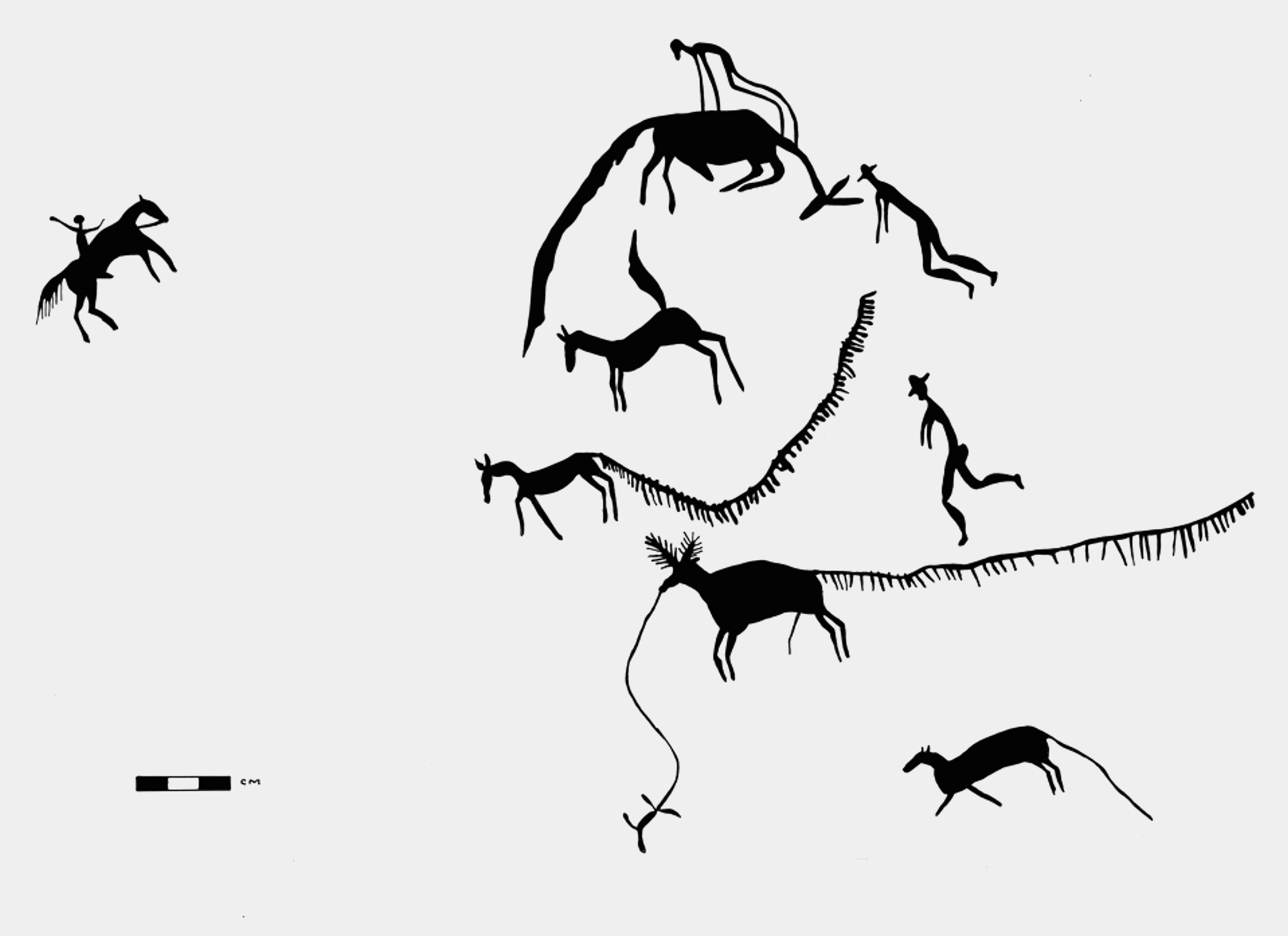

The capture of a manifestation of !khwa, the rain snake or water snake.

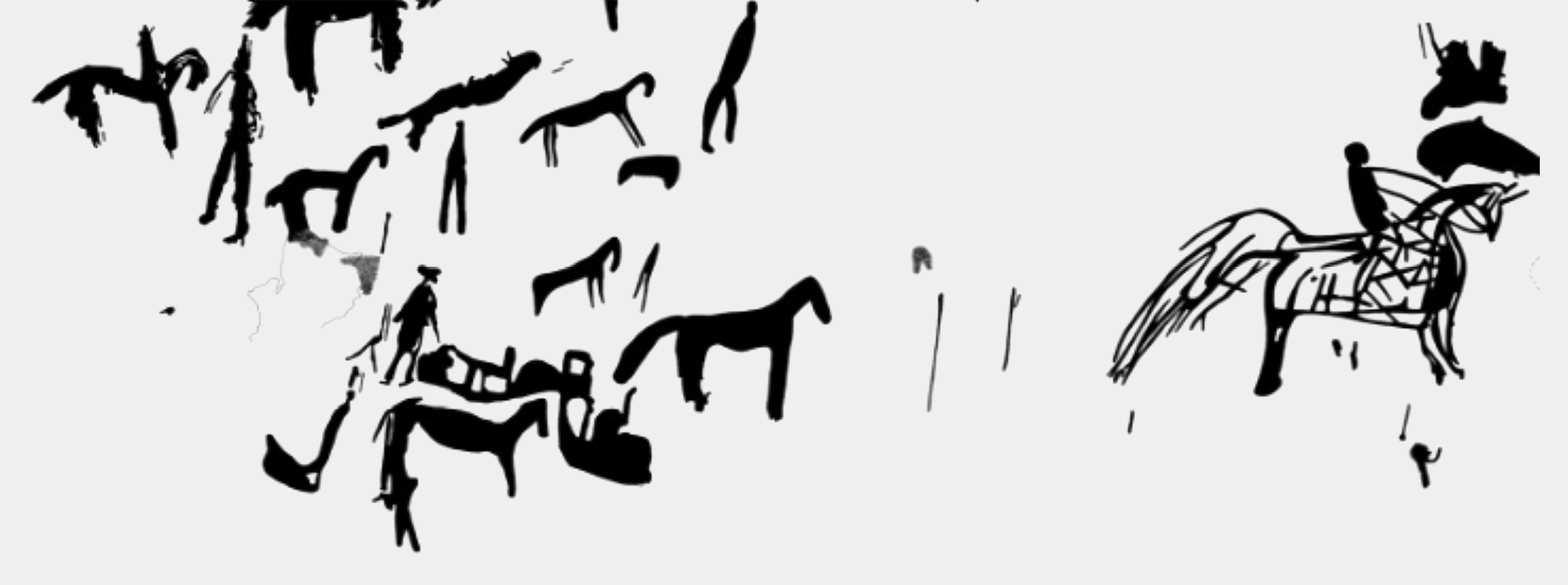

(Left) Shield-bearing warrior in the Maloti-Drakensberg.

(Right) Bull sacrifice of the ‘first fruits’ festival.

Dowson had long suspected that beliefs in the acquisition of rain (from !khwa) were cross-cultural and that the preponderance of rain-making related rock art in the southern Maloti-Drakensberg reflected the protracted relations there between San and farmers – the former making rain for the latter (e.g. Dowson 1994, 1995). He later developed more nuanced reasoning for this scenario, such that fine-line rock art may, in this instance frame something of the client–patron relationship that appears to have prevailed (Dowson 1998; cf. Jolly 1994). Whether or not one believes this led to the aggrandisement of particular rainmakers is debateable, as we have seen.

More recently, Brent Sinclair-Thomson (2016; Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022) has proposed that images of Bantu-speaking warriors with shields might, instead of a ‘record of events’, be those who had commissioned for themselves to be painted in such a way as to exhibit their acquisition of special protective medicines that only the San could provide (Figure 9.5a).

In another development of the patron/client or service provider concept, Jeremy Hollmann (2015) has found clear imagery of San (presumed, owing to the fine- line technique) involvement in African agriculturalist ‘first fruits’ ceremonies (cf. Guenther 1999: 88). In this instance the motif shows a crescent-shaped iron axe raised above the neck of a sacrificial bull [fig 5b]; further evidence of hunter-gatherer engagement in matters ritual of other communities and confirmation, moreover, of the pervasive phenomenon of reverence for the autochthonous first peoples as keepers of arcane knowledge, powerful magic and medicines tied to the land (e.g. Peires 1981: 65).

A tie to the land and first peoples may, in fact be discernible in rock art traditions produced by ‘San- adjacent’ (sensu Skinner 2017) communities that may have, owing to processes of contact and colonisation, become disconnected from their traditions and wished to express a connection with it, however reconfigured (Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022).

Whether these poster-like images were made by ‘ethnic San’, or by the progeny of inter-ethnic marriages through the centuries is not certain, but these images represent a maintenance or replication of ideas held by the San, in the face of the breakdown of Khoe-San trade routes (Harinck 1969) – access to preferred pigments becoming increasingly restricted – and the decimation of Khoe-San society: access to friends, relatives and the wider community becoming increasingly unfeasible (Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022).

It is against the background of marginalisation, the decimation of Indigenous society and the breakdown of communications routes that much of the colonial contact imagery should be viewed. Not only did the communication of trade items and the beliefs that accompanied them become more difficult to maintain, but the concerns of the artists themselves were increasingly altered. New materials entered the subcontinent, sometimes independent of, and sometimes with, the societies that produced them – sheep, cattle, dogs, iron, ceramics, shields spears, guns, horses and wagons – all of which required negotiation or as Andrew Skinner (2017) has put it, ‘brokerage’ (cf. hallis and Skinner 2021). In the heartland of the |Xam San (the informants of the famous nineteenth-century Lloyd-Bleek study) hundreds of horse images made on the patinated boulders of the Strandberg must have been made in a brief florescence of production:

...significant both for its scale relative to the other classes of imagery at the site, and the implication of frontier conditions in the content itself. (Skinner 2017: 135)

At the headwaters of the Mancazana, images made by ‘Bushmen, Hottentots and runaway slaves’.

The historically-specific iteration of Khoe-ness that became the Korana could tap into a number of essentialised ethnicities owing to their multi-ethnic roots and ethnogenetic acquisitiveness. Khoe, San, Griqua, Bergenaars and outlaw Europeans were all contributors and their art arguably reflects their historically-contingent concerns, as noted by Sven Ouzman (2005, Figure 9.8) who had originally pieced together the otherwise-anomalous collection of sites in the eastern Free State region. It seems, however that a swathe of ‘swan-necked’ incised horse images extends further, from the Strandberg to the highlands of Lesotho, constituting ‘equine ephemera’ created as rapidly as the horses could carry it (Skinner and Challis in prep). Horses made the Korana, as they did many smaller, though no less significant, raiding groups of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, vital as they were to maintaining effective defence against others who already had them or at the very least, enabling escape (Mitchell 2015; Challis 2018 inter alia).

Scouring of records produced at the end of the eighteenth century, when the Cape Colony of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) met serious resistance from bands of ‘Bosjesmans’ prompted Brent Sinclair- Thomson (2019, 2021, 2022; Sinclair-Thomson and Challis 2017, 2020; Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022) to survey the mountain rock shelters of the regions supposed to have been their haunts. The French traveller François Le Vaillant (1972 [1790]: 402, 404) had noted that such ‘Boschis-men’ resembled pirates in their heterogeneity, with adherents of all backgrounds (Sinclair-Thomson 2021). The British 1820 settler and abolitionist Thomas Pringle (1835: 98) noted that depredations on his farm were being committed by a group comprising San, escaped slaves of both Khoe-San and foreign descent, as well as military deserters with firearms. Referred to with the catch-all phrase of the day, ‘Bushmen, Hottentots and runaway slaves’ these outlaws were supposed to frequent the headwaters of the Mancazana river in the Winterberg (Napier 1849: 226) as well as the adjacent region of the Tarka valley (Sinclair-Thomson 2021). Hidden rock shelters in this locality have revealed images of livestock: block-colour, fine-line paintings of fat-tailed sheep, cattle, horses with riders holding muskets – and rain-animals. The rain animals speak to the maintenance of Khoe-San beliefs even in the face of unprecedented change. In the 1970s Patricia Vinnicombe had suggested that rain-animals in stock theft rock art surely signified the summoning of the rain to conceal the raiders, wash away their tracks and thwart their pursuers (Vinnicombe 1976: 52). Incorporated in these images of contact are Indigenous animals which at first glance seem incongruous. It transpires, however, that ostriches symbolise for Khoe-San the ability to escape (jumping, as they do, the hunters’ nets), a quality most desirable for fugitives (Sinclair-Thomson and Challis 2020). Baboons, too, are painted alongside images of horses and other colonial-era motifs (Figure 9.9).

The recent discovery of these sites is particularly gratifying because it had been hypothesised that this was the region of the first formations of the so- called ‘Bushmen, Hottentots and runaway slaves’ (Cape Archives 1850 G.H. 8/23: 414-7) that removed to the high Drakensberg mountains north and east (Challis 2012, 2014, 2016). Indeed, Pringle (1835: 137) recorded that there were no raids in this district after 1826 and it is shortly after this time that the famous ‘Bushman Raiders of the Drakensberg’ appear (Wright 1971). Paintings made from the 1830s onwards in the Maloti-Drakensberg show horses and baboons as well as dancing groups in which people are depicted turning into both of these animals (Figure 9.10).

Khoe, San and African farmer religious beliefs concur, owing to millennia of precolonial interaction and syncretisation, that the baboon is a particularly potent locus of magical power associated with protective medicine (Challis 2014). The baboon itself uses the plant root, known as so-|oa among the |Xam San, |u-sõä among Khoe-speakers and uMabobhe among isiXhosa-speakers, to protect it from projectiles and other harmful forces. This, among other things, is what enables the baboon to raid crops and livestock and escape unharmed.

If Sinclair-Thomson’s Tarka ‘banditti’, and the Mancazana band vacated the Winterberg in 1826, and had relocated to the high Maloti-Drakensberg by the 1830s, the intervening years appear to have earned them many dispossessed and disenfranchised isiXhosa- speaking African adherents from the eastern Cape Anglo-Xhosa wars (e.g. Challis 2012, 2016).

Naming themselves for the Xhosa ‘wardoctors’ who protect their warriors with uMabophe, the AmaTola ‘Bushmen’ prosecuted a guerrilla war against the migrant Boer farmers and British settlers, as well as raiding the other San-inflected groups in their neighbourhood. Much like Skinner’s (2017) observation of the Strandberg rock art, horse imagery in the region inhabited by the AmaTola spikes dramatically, such that horses are second in number only to eland, yet produced in a period of approximately 30 years.

This fine line rock art was not, however, made by San. Nor was it made by Xhosa, Khoe, Coloured, Korana, outlaw Europeans, deserters or runaway slaves but by a constantly reconstituting amalgam of all these. Once one examines the historical context in which images were likely being made, the categories of person (especially artist groups) are quite different to those which previous scholars had presented to us. Therefore there is an effective decommissioning of the bounded group – at least in terms of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The groups themselves are not wholly taken out of commission yet their essentialist ethnic identities can no longer be said to obtain. Identity instead coalescing around new forms of emergent society, albeit founded on culturally coherent and cognate precedents. This is the process of creolisation (Challis 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018).

Treating contact and historical images (cattle, shields, horses and guns and so forth), not as records of events, nor markers of ethnicity, but as expressions of indigeneity in the face of change, takes the authors out of their frozen state in the ethnographic present – the San stereotype interacting with more contextually- historicised and dynamic Others – and places them at the forefront of history-making in their own right.

Barham, L. 1992. Let's walk before we run: an appraisal of historical materialist approaches to the Later Stone Age. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 47 (155): 44-51.

Barnard, A. 1992. Hunters and herders of southern Africa: a comparative ethnography of the Khoisan peoples. No. 85. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blundell, G. 2004. Nqabayo’s Nomansland: San rock art and the somatic past. Doctoral dissertation. University of Uppsala.

Bonneau, A., D. Pearce, P. Mitchell, R.Staff, C. Arthur, L. Mallen, F. Brock, and T. Higham 2017. “The earliest directly dated rock paintings from southern Africa: new AMS radiocarbon dates.” Antiquity 91(356): 322-333.

Campbell, C. 1986. Images of war: a problem in San rock art research. World Archaeology 18 (2): 255-268.

Campbell, C. 1987. Art in crisis: contact period rock art in the south-eastern mountains of southern Africa Master’s dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand.

Cape Archives (Government House [G.H.] 23 1850): 417. Statement of William Lochenberg at the Inquiry Held by the Crown Prosecutor Walter Harding and the British Agent in Mpondoland, Henry Francis Fynn, 29th March 1850.

Carter, P. 1978. The prehistory of eastern Lesotho. Doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge.

Challis, S. 2008. The impact of the horse on the AmaTola ‘Bushmen’: new identity in the Maloti-Drakensberg mountains of southern Africa. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford.

Challis, S. 2012. Creolisation on the nineteenth-century frontiers of southern Africa: a case study of the AmaTola ‘Bushmen’ in the Maloti-Drakensberg. Journal of Southern African Studies, 38 (2): 265-280.

Challis, S. 2014. Binding beliefs: the creolisation process in a ‘Bushman’ raider group in nineteenth-century southern Africa. In J. Deacon and P. Skotnes (eds) The courage of ||Kabbo and a century of Specimens of Bushman folklore, 246-264. Johannesburg: Jacana.

Challis, S. 2016. Re-tribe and resist: the ethnogenesis of a creolised raiding band in response to colonisation. In C. Hamilton and N. Leibhammer (eds) Tribing and untribing the archive: identity and the material record in southern KwaZulu-Natal in the late independent and colonial periods, 282-299. Berkeley: University of California Press; Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Challis, S. 2018. Creolization in the investigation of rock art of the colonial era. In B. David and I. McNiven (eds) The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art, 611-633. New York: Oxford University Press.

Challis, S., J. Hollmann, and M. McGranaghan 2013. ‘Rain snakes’ from the Senqu River: new light on Qing's commentary on San rock art from Sehonghong, Lesotho. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 48(3): 331-354.

Challis, S., A. Mullen, and J. Pugin 2015. Rock Art and Baseline Archaeological Survey of the Sehlabathebe National Park, Kingdom of Lesotho: Final Report to the World Heritage Committee of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Challis, S. and A. Skinner 2021. Art and Influence, Presence and Navigation in Southern African Forager Landscapes. Religions 12: 1099.

Challis, S. and B. Sinclair-Thomson, In press. The impact of contact and colonisation on the Indigenous worldview, rock art and history of southern Africa: ‘The Disconnect’. Current Anthropology. Cooke, C. 1965. Evidence of human migrations from the rock art of Southern Rhodesia. Africa 35 (3): 263-285.

d’Errico, F., L. Backwell, P. Villa, I. Degano, J. Lucejko, M. Bamford, T. Higham, M. Perla Colombini, and P. Beaumont 2012. Early evidence of San material culture represented by organic artifacts from Border Cave, South Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (33): 13214-13219.

Dowson, T. 1992. Rock Engravings of Southern Africa. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Dowson, T. 1993. Changing fortunes of Southern African archaeology: comment on A. D. Mazel’s ‘history’. Antiquity 67 (256): 641-644.

Dowson, T. 1994. Reading art, writing history: rock art and social change in southern Africa. World Archaeology 25 (3): 332-345.

Dowson, T. 1995. Hunter-gatherers, traders and slaves: the ‘Mfecane’ impact on Bushmen, their ritual and their art. In C. Hamilton (ed.) The Mfecane aftermath: reconstructive debates in southern African history, 51-70. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Dowson, T. 1998. Rain in Bushman belief, politics and history: the rock art of rain-making in the south-eastern mountains, southern Africa. In The archaeology of rock-art, ed. Christopher Chippindale and Paul Taçon, 73-89. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dowson, T. 2007. Debating shamanism in southern African rock art: time to move on... The South African Archaeological Bulletin 62 (185): 49-61.

Etherington, N. 2001. The Great Treks: The Transformation of Southern Africa, 1815-1854. London: Longman.

Fewlass, H., P. Mitchell, E. Casanova, and L. Cramp 2020. Chemical evidence of dairying by hunter-gatherers in highland Lesotho in the late first millennium AD. Nature Human Behaviour 4, 791–799.

Forssman, T. 2014. The spaces between places: a landscape study of foragers on the Greater Mapungubwe Landscape, southern Africa. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 49 (2): 282-282.

Forssman, T. 2017. Foragers and trade in the middle Limpopo Valley, c. 1200 BC to AD 1300. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 52 (1), 49-70.

Guenther, M. 1975. The trance dancer as an agent of social change among the farm Bushmen of the Ghanzi District. Botswana Notes and Records 7, 161-166.

Guenther, M. 1999. Tricksters and trancers: Bushman religion and society. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Guenther, M. 1986. The Nharo Bushmen of Botswana: Tradition and Change, Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung. Hamburg: H. Buske.

Hammond-Tooke, D. 1998. Selective borrowing? The possibility of San shamanistic influence on Southern Bantu divination and healing practices. South African Archaeological Bulletin 53: 9-15.

Hammond-Tooke, D. 1999. Divinatory animals: further evidence of San/Nguni borrowing, South African Archaeological Bulletin 54: 128-132.

Hammond-Tooke, D. 2002. The uniqueness of Nguni mediumistic divination in southern Africa. Africa 72 (2): 277-292.

Harinck, G. 1969. Interaction between Xhosa and Khoi: emphasis on the period 1620-1750. In L. Thompson (ed.) African Societies in Southern Africa, 145-170. London: Heinemann.

Henry, L. 2010. Rock art and the contested landscape of the North Eastern Cape, South Africa. Master’s dissertation. University of the Witwatersrand.

Hollmann, J. 2007. The ‘cutting edge’ of rock art: motifs and other markings on Driekuil Hill, North West Province, South Africa. Southern African Humanities 19 (1): 123-151.

Hollmann, J. 2014. ‘Geometric’ motifs in Khoe-San rock art: depictions of designs, decorations and ornaments in the Gestoptefontein-Driekuil Complex, South Africa. Journal of African Archaeology 12 (1): 25-42.

Hollmann, J. 2015. Allusions to agriculturist rituals in hunter-gatherer rock art? eMkhobeni Shelter, northern Ukhahlamba-Drakensberg, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. African Archaeological Review 32 (3): 505-535.

Jolly, P. 1994. Strangers to brothers: interaction between south-eastern San and southern Nguni/Sotho communities. Master’s dissertation, University of Cape Town.

Jolly, P. 1995. Melikane and Upper Mangolong revisited: the possible effects on San art of symbiotic contact between south-eastern San and southern Sotho and Nguni communities. South African Archaeological Bulletin 50: 68-80.

Jolly, P. 1996a. Symbiotic interaction between black farmers and south-eastern San: implications for southern African rock art studies, ethnographic analogy, and hunter-gatherer cultural identity. Current Anthropology 37 (2): 277-305.

Jolly, P. 1996b. Interaction between south-eastern San and southern Nguni and Sotho communities c. 1400 to c. 1880. South African Historical Journal 35 (1): 30-61.

Jolly, P. 2006. The San Rock Painting from ‘The Upper Cave at Mangolong’, Lesotho. South African Archaeological Bulletin 61 (183): 68-75.

Lee, N., and H. Woodhouse 1970. Art on the rocks of southern Africa. New York: Scribner and Sons.

Le Vaillant, F. 1972 [1790]. Travels from the Cape of Good Hope Into the Interior Parts of Africa, Including Many Interesting Anecdotes, with Elegant Descriptive of the Country and Inhabitants... Translated from the French. New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation.

Lewis-Williams, D. 1981. Believing and seeing: symbolic meanings in southern African rock art. New York: Academic Press.

Lewis-Williams, D. 1982. The economic and social context of southern San rock art. Current Anthropology 23 (4): 429-449.

Lewis-Williams, D. 1983. The rock art of southern Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis-Williams, D. 1984. The empiricist impasse in southern African rock art studies. South African Archaeological Bulletin 39 (139): 58-66.

Lewis-Williams, D. 1993. Southern African archaeology in the 1990s. South African Archaeological Bulletin, 48 (157): 45-50.

Lewis-Williams, D. 1995. Modelling the production and consumption of rock art. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 50: 143-154.

Lewis-Williams, D. 1998. Quanto?: The issue of ‘many meanings’ in southern African San rock art research. South African Archaeological Bulletin 53: 86-97.

Lewis-Williams, D., T. Dowson, and J. Deacon 1993. Rock art and changing perceptions of southern Africa's past: Ezeljagdspoort reviewed. Antiquity, 67 (255): 273-291.

Loubser, J. and G. Laurens 1994. Depictions of domestic ungulates and shields: hunter/gatherers and agro-pastoralists in the Caledon River valley area. In T. Dowson and D. Lewis-Williams (eds) Contested images: diversity in southern African rock art research, 83-118. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Mallen, L. 2008. Rock art and identity in the North Eastern Cape Province. Master’s dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand.

Manhire, A., J. Parkington, A. Mazel, and T. Maggs 1986. “Cattle, sheep and horses: a review of domestic animals in the rock art of southern Africa.” South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series, 5: 22-30.

Marshall, L. 1976. The !Kung of Nyae Nyae. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press.

Marx, K. 1867. Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen Oekonomie. Volume 1: Der Produktionsprozess des Kapitals (1 ed.). Hamburg: Verlag von Otto Meissner.

Mazel, A. 1989a. People making history: the last ten thousand years of hunter-gatherer communities in the Thukela Basin. Southern African Humanities 1 (07): 1-168.

Mazel, A. 1989b. Changing social relations in the Thukela Basin, Natal 7000-2000 BP. South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 6: 33-41.

Mazel, A. 1992. Changing fortunes: 150 years of San hunter-gatherer history in the Natal Drakensberg, South Africa. Antiquity 66 (252): 758-767.

Mazel, A. 1993. Rock art and Natal Drakensberg hunter-gatherer history: a reply to Dowson. Antiquity 67: 889-889.

Mazel, A. 2009. Unsettled times: shaded polychrome paintings and hunter-gatherer history in the southeastern mountains of southern Africa. Southern African Humanities 21 (1): 85-115.

Mazel, A. 2013. Paint and Earth: constructing hunter-gatherer history in the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg, South Africa. Time and Mind 6 (1): 49-57.

McGranaghan, M. 2016. The Death of the Agama Lizard: the historical significances of a multi-authored rock-art site in the Northern Cape (South Africa). Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26 (1): 157-179.

McGranaghan, M. and S. Challis 2016. Reconfiguring hunting magic: Southern Bushman (San) perspectives on taming and their implications for understanding rock art. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26 (4): 579-599.

Mitchell, P. 2002. The archaeology of southern Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mitchell, P. 2010. Making history at Sehonghong: Soai and the last Bushman occupants of his shelter. Southern African Humanities 22 (1): 149-170.

Mitchell, P. 2015. Horse Nations: The worldwide impact of the horse on indigenous societies post-1492. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, P. 2016. Africa from MIS 6-2: Where Do We Go from Here? In S. Jones and B. Stewart (eds). Africa from MIS 6-2: Population Dynamics and Paleoenvironments, 407-416. Dordrecht: Springer.

Morris, D. 2006. Interpreting Driekopseiland: the tangible and the intangible in a Northern Cape rock art site. South African Museums Association Bulletin, 32 (1): 40-45.

Mullen, A. 2018. Re-investigating Significantly Differentiated Figures in the rock art of the south-eastern Mountains. Master’s dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand.

Mullen, A. 2020. Dateless substance. White Pigments in the Rock Art of Southern Africa. Lesedi 23: 69-73.

Napier, E. 1849. Excursions in southern Africa: including a history of the Cape Colony, an account of the native tribes etc. London: William Shoburl.

Ouzman, S. 2003. Indigenous images of a colonial exotic: imaginings from Bushman southern Africa. Before Farming 1: 1-23.

Ouzman, S. 2005. The magical arts of a raider nation: central South Africa's Korana rock art. South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 9: 101-113.

Pargeter, J., A. MacKay, P. Mitchell, J. Shea, and B. Stewart. 2016. Primordialism and the ‘Pleistocene San’ of southern Africa. Antiquity 90 (352): 1072-1079.

Pearce, D. 2010. The Harris matrix technique in the construction of relative chronologies of rock paintings in South Africa. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 65 (192): 148-153.

Peires, J. 1981. The house of Phalo: a history of the Xhosa people in the days of their independence. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pringle, T. 1835. Narrative of a residence in South Africa. London: Edward Moxon.

Russell, T. 2000. The application of the Harris matrix to San rock art at Main Caves North, KwaZulu-Natal. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 55: 60-70.

Russell, T. 2012. No one said it would be easy. Ordering San paintings using the Harris Matrix: dangerously fallacious? A reply to David Pearce. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 67 (196): 267-272.

Silberbauer, G. 1982. Political process in G|wi bands. In E. Leacock and R. Lee Politics and history in band societies, 23-35. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. 2016. Martial art: connections between farmers and foragers in the nineteenth-century Eastern Cape. Honours dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. 2019. Indigenising the gun–rock art depictions of firearms in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. In J. Goldhahn (ed.) Rock Art Worldings, Part 1, Special Issue, Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture: 121-135.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. 2020. Trouble on the Tarka: the history of bandit groups on the Cape Colony’s eastern border and the archive of their rock art. International Journal of Historical Archaeology.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. In press. Escape and abscond: the use of ostrich potency by nineteenth-century rock artists, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. and S. Challis, S. 2017. The ‘bullets to water’ belief complex: a pan-southern African cognate epistemology for protective medicines and the control of projectiles. Journal of Conflict Archaeology, 12 (3): 192-208.

Sinclair-Thomson, B. and S. Challis, S. 2020. Runaway slaves, rock art and resistance in the Cape Colony, South Africa. In S. Wynne-Jones and H. Rødland (eds) Archaeological approaches to slavery and unfree labour in Africa, Special Issue. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 55 (3): 475-491.

Skinner, A. 2017. The changer of ways: rock art and frontier ideologies on the Strandberg, Northern Cape, South Africa. Master’s dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand.

Skinner, A. and S. Challis. In prep. Indigenous navigation in a colonised landscape: the New Animisms and the brokering of relations by insurgent resistance groups in nineteenth-century southern Africa.

Smith, B. 2010. Envisioning San history: problems in the reading of history in the rock art of the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa. African Studies, 69 (2): 345-359.

Smith, B. and S. Ouzman. 2004. Taking stock: identifying Khoekhoen herder rock art in southern Africa. Current Anthropology 45 (4): 499-526.

Stewart, B., Y. Zhao, P. Mitchell, G. Dewar, J. Gleason, and J. Blum. 2020. Ostrich eggshell bead strontium isotopes reveal persistent macroscale social networking across late Quaternary southern Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (12): 6453-6462.

Swart, J. 2004. Rock art sequences in uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Park, South Africa. Southern African Humanities 16 (1): 13-35.

Thorp, C. 1997. Evidence for interaction from recent hunter-gatherer sites in the Caledon Valley. African Archaeological Review 14 (4): 231-256.

Vinnicombe, P. 1960. General notes on Bushman riders and the Bushmen's use of the assegai. South African Archaeological Bulletin 15 (58): 49-49.

Vinnicombe, P. 1976. People of the eland: rock paintings of the Drakensberg Bushmen as a reflection of their life and thought. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Voss, B. 2008. The archaeology of ethnogenesis: race and sexuality in colonial San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wadley, L. 1987. Later Stone Age hunters and gatherers of the southern Transvaal: social and ecological interpretation (Vol. 25). Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

Wadley, L. 1989. Legacies from the Later Stone Age. South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 6: 2-53.

Wadley, L. 1996. Changes in the social relations of precolonial hunter–gatherers after agropastoralist contact: an example from the Magaliesberg, South Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 15 (2): 205-217.

Wadley, L. (ed.) 1997. Our gendered past: archaeological studies of gender in southern Africa. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Wiessner, P. 1998. On network analysis: The potential for understanding (and misunderstanding) !Kung Hxaro. Current Anthropology, 39 (4): 514-517.

Willcox, A. 1963. The rock art of South Africa. Johannesburg: Thomas Nelson and Sons.

Witelson, D. 2019. A painted ridge: rock art and performance in the Maclear District, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 98. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Wright, J. 1971. Bushman raiders of the Drakensberg, 1840-1870: A study of their conflict with stock-keeping peoples in Natal. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press.

Wright, J. 1978. San history and non-San historians. In Collected Seminar Papers. Institute of Commonwealth Studies 22: 1-10. Institute of Commonwealth Studies.

Wright, J. 2007. Bushman raiders revisited. In P. Skotnes (ed.) Claim to the country: The archive of Lucy Lloyd and Wilhelm Bleek, 119-129. Johannesburg: Jacana Press.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation