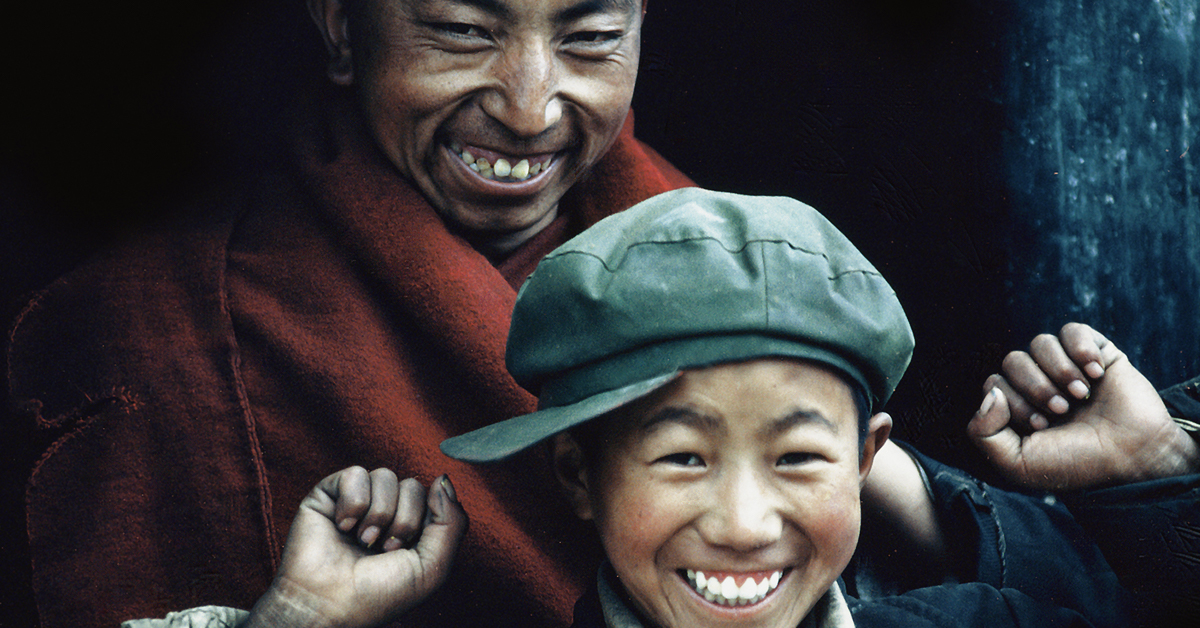

Robert Hefner III has been exploring physical and metaphysical terrains all his life. As a founding member of the Bradshaw Foundation - and its President - over the years Hefner has also helped draw the world's attention to 'cultural' terrains, including some of its earliest manifestations. His fascination with rock art has driven his encouragement and support for the discovery, documentation and preservation of this cultural heritage. This is an account of his rock art expedition to Tibet in 1990.

After a long and interesting day of travel by jeep from Lhasa with a Chinese driver, with stops at Yangbajing (a town comprised of steam, geysers, hot springs, a few drilling rigs, and a thermal electric plant that supplies Lhasa) and Damxung (a 'boardwalk' village with the distinct look of the American wild west), we arrived through a series of steep switchbacks at the 5,132 metre crest of the Lar-geh La Pass in Tibet.

As we jumped from the jeep to take photographs, we were confronted by one of the most spectacular views of a lifetime, while at the same time feeling we were standing on top of the world! The deep blue Tibetan sky encompassed barren, craggy, rocky peaks, full of spectacular geological structures typical of the Tibetan plateau. Beside the road was a pile of carved religious rocks and a pole with many fluttering prayer flags. Only 300 metres below was a sapphire lake enclosed by snowy peaks: the great valley of Lake Namtso.

It was mid-summer and the otherwise totally barren plain was covered with the grassy vegetation of a bog, the valley and surrounding mountains seemed to be glacially carved and wind eroded, the rocky remnants now and then surrounding the lake appeared to be water carved, and the water was salty and brackish; Lake Namtso was apparently drying up. Before this great drying period, features such as a pair of great pillars were cut by the water's action during a geological period when the lake was 30/40m higher than it is today.

According to local nomads, the lake requires about 20 days to circumnavigate on horseback. The lake is surrounded by a number of holy places (equivalent to American Indian 'power places') and small 'gompas', i.e., Buddhist shrines or small temples built mostly within small caves approximately 15 to 20 metres deep and 5 to10 metres high in limestone remnants surrounding the lake. Near one such gompa we encountered over 100,000 beautifully carved Tibetan stones forming a wall over one metre tall by one metre wide and stretching at least 300 metres along the shore of Lake Namtso.

After studying the magnificent detail of several 'religious stones' along this wall, we scrambled over them and headed through the clear, shimmering and pollutionless air of Central Tibet. We tested the water on the shore of Lake Namtso, jumped in and started swimming to relieve our parched skin from that hot sun. But in just seconds we raced back to the bank to recover from the shockingly cold water a short distance out from shore. We had not stopped to think that the water covering the shallow bank's rocks was being heated by the radiant sun, masking the unbelievably frigid water just beyond.

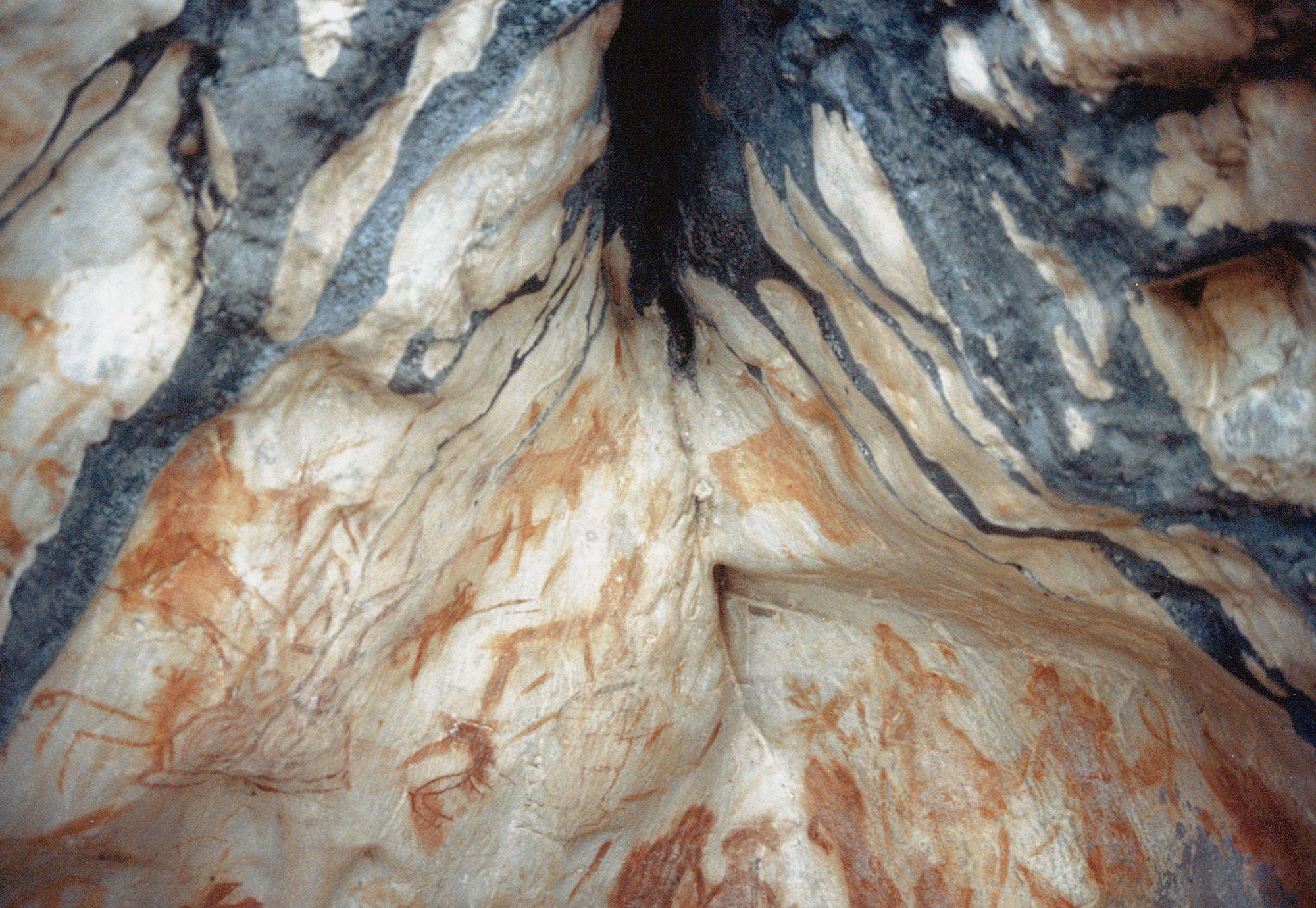

In the late afternoon the other travellers started thereturn to camp and I too began walking in that direction. However, I spotted one in our party heading in another direction and immediately joined her. It was there we discovered two small caves about 3 or 4 metres high and about 2 or 3 metres deep at the entrance, the rock walls covered with incredible paintings.

They were so well preserved my first thought was that during the Cultural Revolution some Chinese in the area had decided to create these drawings to play a joke on future tourists. In any event, the drawings were so beautiful and fascinating that we began to photograph them for our own enjoyment!

While taking the snapshots I began to think I might be mistaken in my scepticism. Why shouldn't these drawings be well preserved? Located safely out of the direct weather and in an incredibly stable, dry, pollution-free environment, they were protected from destruction or decay and were most likely intact. Additionally the caves are in an area frequented only by a few monks on holy pilgrimages or the occasional nomad herding the few yaks who can exist on the sparse grasses of the lake bog.

The walls of these caves were of quite smooth, off-white limestone which appeared to be water cut and stained by a blue mineral, possibly azurite. The drawings were spectacularly clear, and we photographed almost all that we saw.

The figures are drawn in red to reddish-brown and yellow-brown pigment, most being 15 to 25 centimetres tall. Some appeared to be quite similar to photographs of rock drawings of horned animals and horses we had seen in museums. Many of the animals and people in the drawings had an oriental appearance: one particular drawing was about 20 centi- metres tall and seemed quite oriental, the person dressed in a typical oriental gown or robe. I wondered if this drawing could have been added much later than some of the work that appeared to be more primitive?

Unfortunately I could not study the pictures carefully enough to determine whether or not one could clearly discern different periods for the drawings. I leave that task to readers who might possibly go to Tibet and visit this off-the-beaten path, glorious and holy place. It is a dream fulfilling journey and well worth the effort of travelling there.