George Nash

Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool

The Kilmartin Valley (also known as Kilmartin Glen) is located within the county of Argyll and Bute in Western Scotland and covers an area of approximately 55 km2 (11 km [north-south] x 5 km [east-west]). It has within its curtilage one of the largest and most complex later prehistoric landscapes in northern Britain. Over the past 190 years or so, the area has been the focus for landscape prospection, excavation and research (e.g., Bradley 1997; Campbell and Sandeman 1962; Currie 1830; Greenwell 1866; Jones 2001, 2005, 2006; Jones et al 2011; Nash 2015, Barnett et al. 2021). Monuments include a variety of Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (EBA) stone-chambered burial ritual monuments (including long cairns, round cairns, barrows and cists), a henge, standing stones and engraved open-air rock art. The Royal Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments for Scotland (RCAHMS) lists over 150 later prehistoric sites within a nine-kilometre radius of the central valley section. Engraved rock art is found on or close to burial monuments and as open-air sites on exposed rock outcrops.

In 2015 and 2021, a team of archaeologists from the Welsh Rock Art Organisation (WRAO) began a study on the Later Prehistoric sites that contained rock art in Western and Northern Britain. This study followed an earlier research project which concentrated on a corpus of open-air sites. One of the areas included in this study covered the southern, central, and northern sections of the Kilmartin Valley.

This paper assesses and discusses some of the findings of this project, suggesting that rock art provided a ritual link between monuments, landscape and water. The focus of this paper will be the small but significant assemblage of Late Neolithic/EBA stone chambered monuments, cists and standings stones that occupy the lower, central and upper sections of the valley, extending from the village of Kilmartin and the rugged foothills in the north to the marshy grassland of Mòine Mhòr in the south.

Over the past 50 years or so there has been a resurgence in research of prehistoric rock art tradition in the British Isles, initially through fieldwork and cataloguing data (e.g., Forde-Johnson 1956, Lynch 1970; Morris 1977, Shee-Twohig 1981; Beckinsall 1999; Sharkey 2004,) and later discussions and interpretations (e.g. Sharpe 2007; Bradley 2009; Meirion Jones 2012; Needham, Cowie & McGibbon 2012; Mazel, Waddington & Nash 2007; Mazel & Nash 2022). As a result of focusing on specific areas that contain rock art, in this case, Kilmartin, a broad synthesis for British and Northern European traditions have been formulated (e.g. O’Sullivan 1986; Cunliffe 2004; Waddell 2005; Mazel, Nash & Waddington 2007; Cochrane & Meirion Jones 2012).

The Monuments and Motifs Project (MMP) was inaugurated by the author in 2015, following several expeditions to a number of Neolithic core areas within the British Isles. Later research expeditions were undertaken and were concerned with the Atlantic open-air rock art assemblage that occupied much of the upper reaches of the valley. It became apparent that there was an inextricable link between monument building and use, landscape position, artefact behaviour and rock art (e.g., Tilley 1989; Bradley 1993; Nash 2012).

A range of issues and concerns affects the awareness of rock art and its protection needs:

- Was rock art being incorporated within the design and construction of Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age stone chambered burial-ritual monuments, cist, and standing stones or was rock art being commissioned sometime after the monuments were constructed?

- Were the design influences directly and/or indirectly originating from Ireland (forming part of a wider Clyde-Carlingford Group connection between Western Scotland and Southern Ireland)?

- Were the design concepts for rock art from within and outside monuments later incorporated onto open-air panels?

- Are there similar landscape patterns and monument-clustering found in other Later Prehistoric monument concentrations elsewhere?

- Finally, did the surrounding environment - in particular, the close proximity of water - play a role between the monument location and the choice of rock art symbols used?

In terms of contextualising both the monuments and the rock art, the MMP explored a number of core areas that contained Atlantic-style rock art including the Boyne Valley (County Meath, Ireland), Loughcrew (County Meath, Ireland), North Wales (including Ynys Môn [Anglesey]), North-west England and Kilmartin Valley (Argyll and Bute). From these five areas, a number of stylistic and spatial patterns began to emerge. Using the motif classification established by Shee-Twohig (1981), several motifs appeared to have been consistently applied to monuments from the five study areas including cupmarks, concentric circles and cup-and-rings. However, in addition to these simple motifs, prehistoric artists from each study area appear to have used other motifs as well, probably as a means of establishing local and regional identity. In County Meath (central-eastern Ireland), communities used a wide repertoire of motifs, in particular on the kerbing of the large passage graves of Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth in the Boyne Valley and within the chamber and passage areas of the monuments that form the Loughcrew group of passage graves (O'Kelly 1982; Eogan 1986; Cooney 2000). In the case of the communities constructing and using the stone chambered monuments in Kilmartin, cupmarks, design variations of concentric circles, cup-and-rings, and flat-butted axes are the most numerous motifs used. One can postulate that this artistic style represented a limited number of communities that occupied this fertile landscape and who used this limited repertoire of symbols to convey ownership, stewardship and connectivity (e.g., Valdez-Tullett 2019).

Rock art within a burial-ritual context is usually confined to Neolithic passage graves, the Boyne Valley and Loughcrew Groups being the most cited monuments; however, not all burial-chambered monuments possess rock art. In Ireland, for example, only c. 45 free-standing burial monuments out of a total of 1500 contain engraved rock art (Waddell 2005). It has been suggested that engraved and painted rock art, which has its origins in the Mediterranean and along the coastal fringes of the Iberian Peninsula, may have been part of a secondary wave of ideas accompanying monument building and in use along the Atlantic fringe of Western Europe (Nash 2012). In addition to the Irish examples mentioned above, several notable passage graves of Late Neolithic date are found in Northwest Wales and one other in Calderstones Park, Liverpool, each containing a wealthy repertoire of imagery. It is more than likely that rock art formed only part of a much more complex package of ideas associated with death, burial and ritual. Decorated ceramics, portable stone artefacts, [engendered] jewellery and flint tools, and even subtle changes in architecture and the construction of quartz pavements all played their part in making these places special.

Despite a 4-6000-year interval between what we witness today and when these sites were under construction, in use, and later abandoned, there has been much change to both the landscape form and the vegetation cover. Monument representation is also different, with probably many potential sites being destroyed, altered, or remaining undiscovered. In this short paper, I have focused on those monuments that contain rock art. Arguably, I have resisted (perhaps wrongly) numerous open-air rock panels that occupy the valley slopes, especially those sited along the western and northern sections of the valley (e.g., the sites of Achnabreck (NGR NR 855 906) (Figure 1), Baluachraig (NGR NR 831 969) (Figure 2), Blarbuie (NGR NR 890 898), Cregantairbh (NGR NM 843 012) and Ormaig (NGR NM 822 027[to name but a few]. Interestingly, and despite having the same motifs, these open-air sites occupy different locates to the Late Neolithic burial sites and, arguably their associated landscape monuments (i.e., standing stones).

The topography and weathering in and around the Kilmartin Valley have had a major influence on how later prehistoric communities organised their ritual landscape. It is more than probable that the ritualisation of the landscape developed during the Mesolithic period (10 kyr to 4 kyr). At this time, the focus on ritual practices was tied to natural forms within the landscape. From the Neolithic and beyond, the focus was on statementing the landscape with monoliths, rock art and burial ritual monuments. This process continued for at least three millennia. Landscape monuments and rock art sites took full advantage of the local geology.

The base geology of the valley comprises a series of laminated schists that have been shaped during the Quaternary period by a series of glacial episodes, the most severe occurring between 70 and 10 kyr, followed by a settled and temperate climatic episode that spanned much of the Holocene (from 10 kyr until present); in this case, running water replaces ice. Evidence for glacial scouring and ice-flow direction is revealed on the exposed rock outcropping, along with cracking and fracturing of rock surfaces which probably occurs during periglacial conditions (during the Late Pleistocene/early Holocene). It was probably from around 12 kyr that much of Scotland was ice-free; however, the vast quantities of meltwater and solifluction debris, along with rapidly rising sea level (coupled with isostatic rebound of the landmass) created a landscape that was - and is - in constant flux. In several instances, land rise rates exceeded sea level rise. Arguably, these dynamic changes in, say, the water table throughout the valley, would have influenced when and where Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments would have been sited. Moreover, tomb builders and communities may have formed an intimate relationship between water, water velocity, water ebb and flow and water-free terrain.

The palaeosedimentological regime during the early Holocene initially comprised a large, raised beach, developing on either side of the Kilmartin Burn, the result of meltwater and periglacial deposition, along with sediment accumulation from sea inundation, especially within the southern section of the valley.

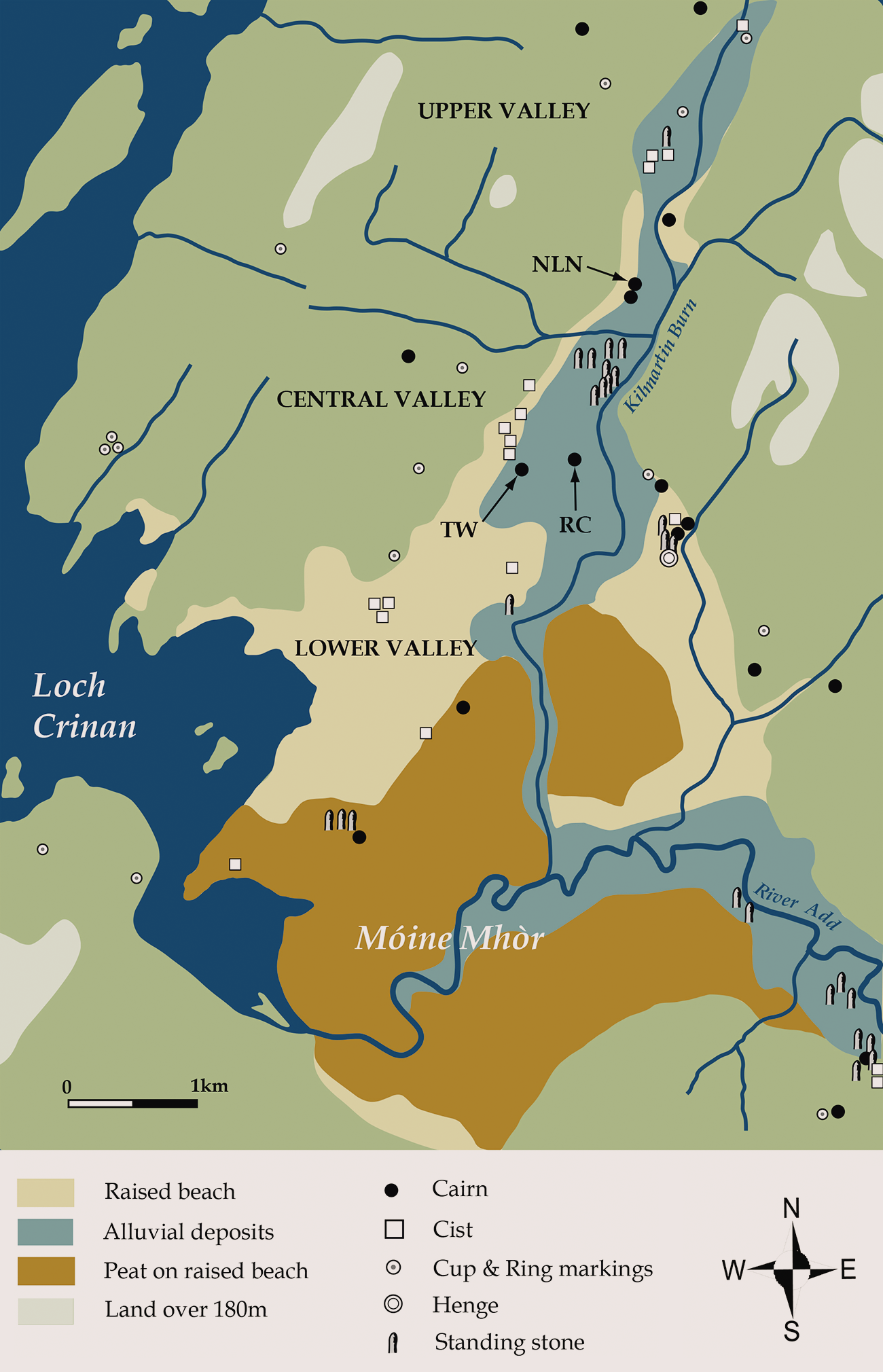

Feeding into the Kilmartin Burn is a series of streams that run off the craggy uplands that stand east and west of the valley. The current sea level spot heights within the southern section of the valley range between 3 and 4m AOD. In and around the Nether Largie Group, they range between 11 and 16m AOD. At the head of the valley, the mean height above sea level is 30m AOD. The heights are taken from land that is formed from Alluvial deposition (i.e., ground that lies east and west of the Kilmartin Burn). The topographic ratio between low and high ground has changed little, with the low ground at the foot of the valley and the high ground at its head. Assuming that this is a general principle, one can postulate that sea level rise following the glacial epoch inundated the lower section of the valley, creating (initially) a large, brackish, saltwater marsh area. Later, this marshland area would have formed substantial peat deposits. Sea inundation may have extended some way up the valley to a few hundred metres south of the site of Ri Cruin (NGR NR 82538 97115). Beyond this, and prior to the canalisation of the Kilmartin Burn, the river would have been wider and following probably a much different course than today. The river would have encountered many natural obstacles that were remnants of periglacial activity, including lateral and terminal moraine deposition. One can assume that access to these and other monuments constructed to the south of the Nether Largie Group would have had to navigate the valley via a series of pathways or by boat, especially if communities were approaching the valley from the south. Many of the Neolithic cairns appear to have a direct association in terms of monument proximity and landscape setting. The majority of the landscape monuments, such as the standing stones of Ballymeanoch (NGR NE 833 964) and Nether Largie (NGR NR 828 976), occupy alluvial areas of the valley and stand close to the course of the Kilmartin Burn and south, along the nearby River Add (Figure 3). The standing stones appear to be arranged in groups, usually orientated north-south and running parallel with the major river courses. It is conceivable that this particular group of landscape monuments acted as processional markers that would have guided communities (and their dead) from those areas where settlement was located, to the final resting places within the sacred sections of this and other valleys to the south. The standing stones and their proximity to running water clearly indicate an association between the natural and sacred parts of the valley. Interestingly, the standing stones are usually sited on the western side of watercourses (e.g., The monolith group of Ballymeanoch (Stones A, B, C & D) and the single monoliths of Stone F (Nether Largie) and Torbhlaran).

During the Early Bronze Age, the raised beach within the southern part of the valley – Móine Mhòr, was beginning to be covered by a substantial peat sequence, surrounding the later prehistoric settlement and fort of Dunadd (NGR NR 837 935). The peat formation was the result of climatic amelioration when much of North-western Europe began to experience wetter conditions. Located on this deposit is a series of landscape monuments, along with several cairns and a cist. This monument group, occupying the western edge of the part formation would have been constructed after 2500 BCE.

The distribution of later prehistoric monuments within the Kilmartin Valley (NLN = Nether Largie North; RC = Ri Cruin; TW = Temple Wood).

Associated with Neolithic monuments are the first farming communities that begin to introduce domesticates and cereal cultivation to the valley at around 4000 BCE.

The distribution pattern for Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments is quite distinct, with Neolithic stone-chambered cairns occupying the central and upper parts of the Kilmartin Valley, while the Bronze Age cairns and cists are located either within the side valleys on top of prominent ridges or within the peripheral areas of the Kilmartin Burn (Figure 3). Scattered throughout the valley and encroaching several of the side valleys are a number of standing stones (or monoliths); these are either single entities or are positioned in multiples, sometimes forming groups known as stone rows. A number of these monument groups contain engraved rock art, the most dominant symbols being cupmarks and cup-and-rings. Despite the high concentration of monuments within the Kilmartin Valley, researchers consider that many chambers and cists were emptied during the age of the antiquarian. In addition, modern farming practices and peat cutting within the Mòine Mhòr area has caused damage to - or complete destruction of - a number of monuments (Tipping 2008, 6).

Identified within the valley are at least 41 stone-chambered and non-chambered burial-ritual monuments, along with seventeen standing stones, one henge, and one stone circle complex (RCAHMS 2008). Many of these monument groups - including the long cairns - contain no rock art. This architecturally distinct and diverse group of monuments are located mainly within the central and upper sections of the valley where the valley floor narrows, and the valley sides are steep. The stone-chambered monuments are assigned mainly to the Late Neolithic period, while the thirty or so cairns and barrows date from the Early Bronze Age; both groups span a period of around a thousand years and a small number contain engraved Atlantic-style rock art (Table 1). It is probable that the earliest group - the stone-chambered tombs - are also in use during the Early Bronze Age, forming a united group of monuments, along with later chambered barrows, cairns, and cists; collectively representing the ritual use of the landscape by at least 60 generations of community. In several instances, there are clear additions and changes in monument design which is probably the result of hybridisation of different elements of monument architecture which also occur outside the valley. As part of this merging of different architectural styles, engraved rock art has been added to earlier and later monuments, thus establishing a wide homogeneous time frame.

An inventory of free-standing monument rock art sites within the Kilmartin Valley (adapted from RCAHMS 2008)

Site Name |

RCAHMS No. |

Monument Type |

Grid Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

Carn Bàn |

36 |

Cairn |

NR 840 907 |

Rock Art: Pecked multiple lozenges on one face and recent chiselled marks on rear of large stone. |

|||

Glennan |

58 |

Cairn |

NM 856 011 |

Rock Art: Two cairns, with the northern cairn possessing a covering slab containing at least nine cupmarks. |

|||

Nether Largie Mid |

67 |

Cairn |

NR 830 983 |

Rock Art: Large circular multi-cisted-cairn located on a low gravel terrace. This monument is now much denuded. The covering slab from one cist contains a single cupmark and an axe motif. |

|||

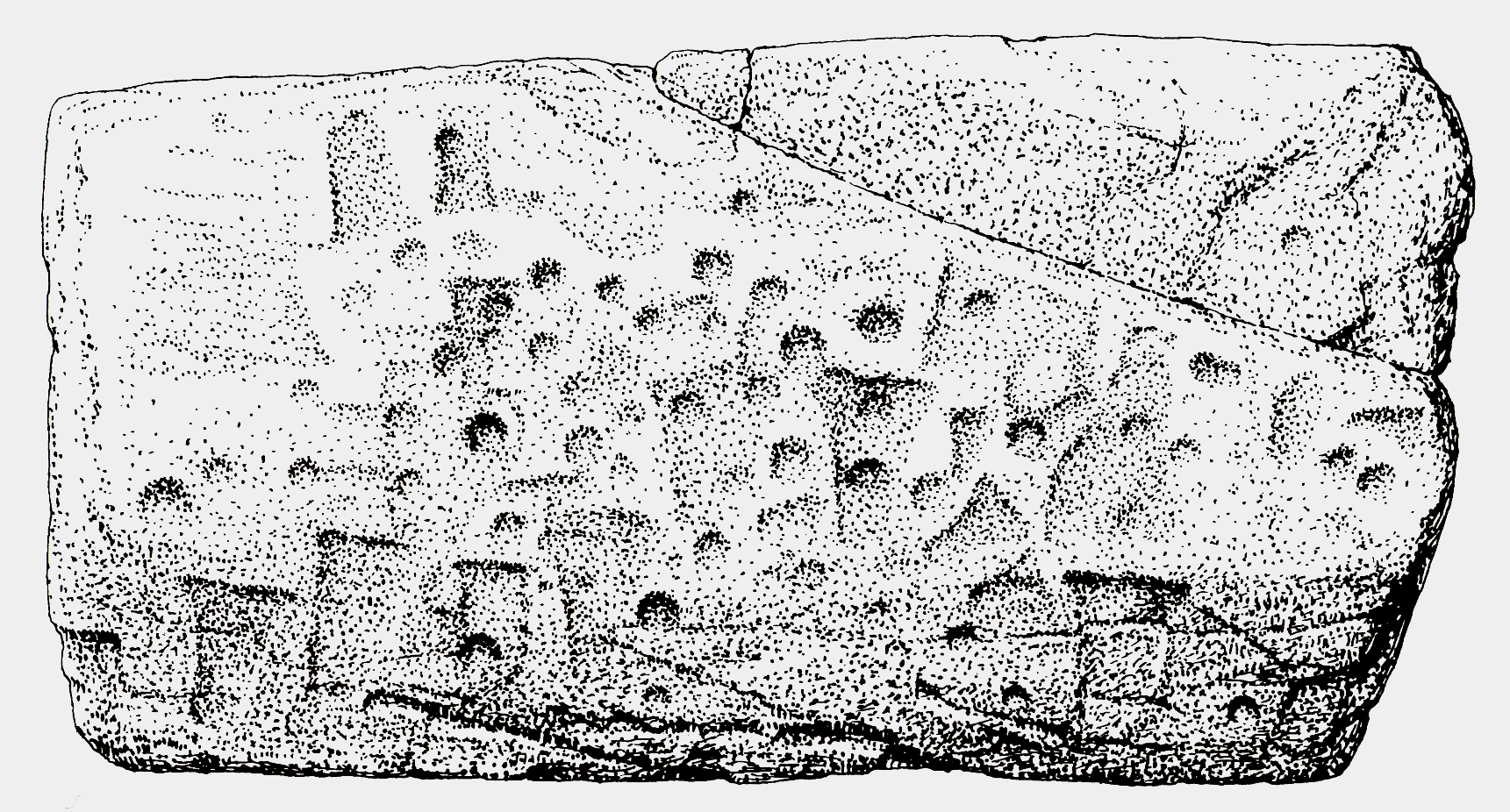

Nether Largie North (NLN) |

68 |

Cairn |

NR 830 094 |

Rock Art: Three stones including a large covering slab (underside), cist wall and stone fragment. Rock art from these stones includes a series of axes, circles and cupmarks. |

|||

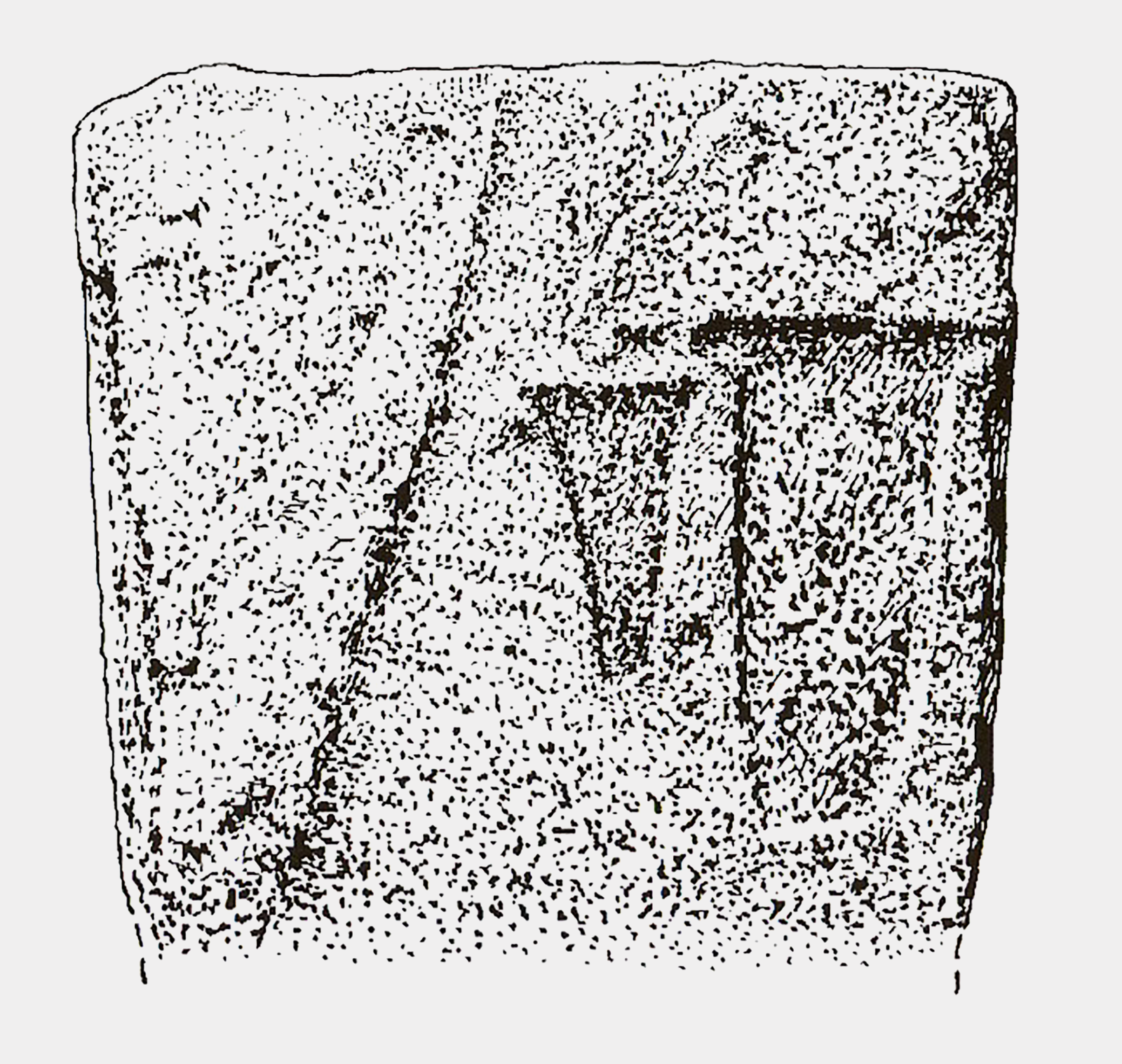

Ri Cruin (RC) |

76 |

Cairn |

NR 825 971 |

Rock Art: Decorated east wall slab comprising multiple axe motifs and a linear barb, interpreted as a halberd (see Needham, Cowie & McGibbon 2012) but more likely to be a stylised boat. |

|||

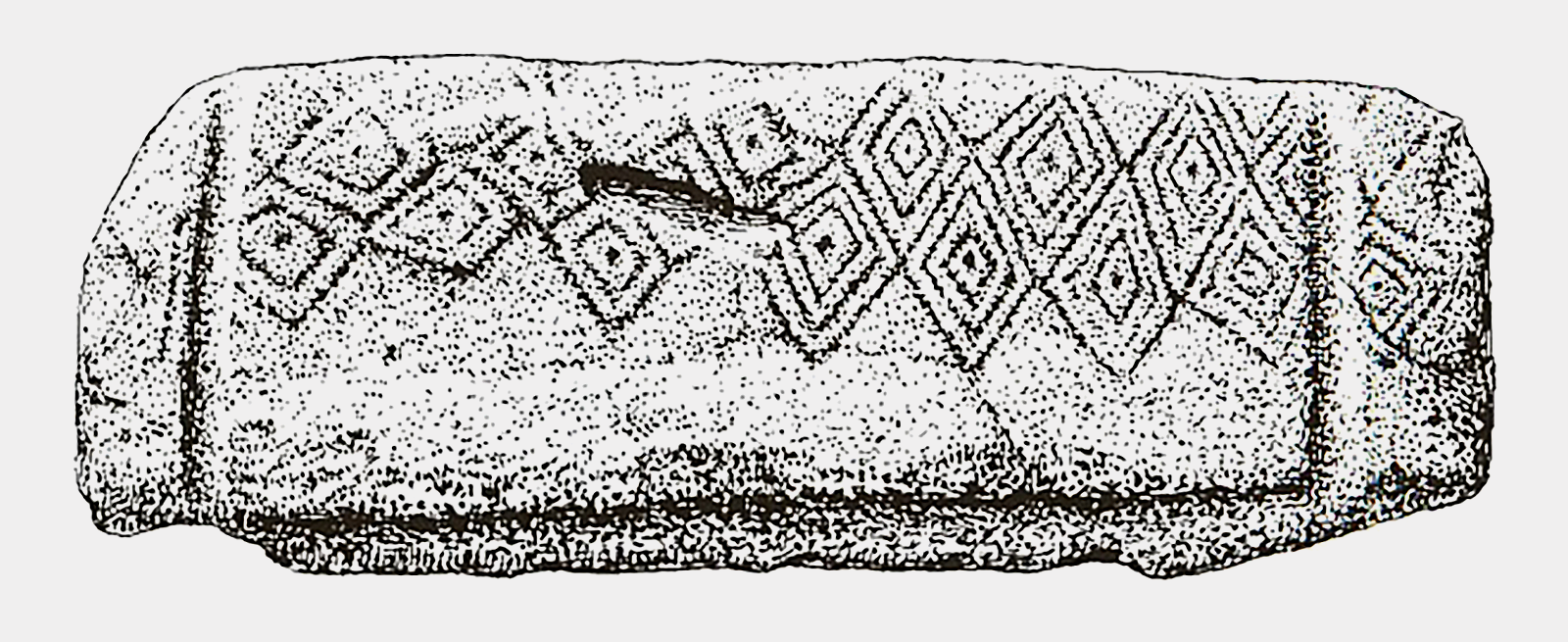

Badden |

81 |

Cist |

NM 858 890 |

Rock Art: Side slab, discovered during ploughing and containing multiple double and triple-lined lozenges, enclosed in a rectilinear rebate. |

|||

Dunchraigaig Cairn |

48 |

Later prehistoric cairn with a central and larger SE cist |

NR 833 968 |

Rock Art: The site was excavated in 1868 by Greenwell. Found in 2021 was an engraved panel featuring five cervids, two of which are red deer stags. The underside panel formed part of a large capstone covering the SE cist. |

|||

Killbride |

98 |

Cist |

NR 833 968 |

Rock Art: A severely ruined cist was discovered in 1982 with one of the side slabs containing three roughly- pecked triangular motifs. |

|||

Ballymeanoch |

199 |

Standing Stone group (Stones A to G) |

NE 833 964 |

Rock Art: Standing stone group located close to the Ballymeanoch Henge. Originally seven stones, now six remain. Two stones are decorated with multiple cupmarks, concentric circles and cup-and-rings, several with a single grooved line. From the same group, an excavated stone (Stone G) contained an hourglass perforation and cutmarks. |

|||

Nether Largie Group |

222 |

Standing Stone group (Stones A to N) |

NR 828 976 |

Rock Art: Standing stone cluster, organised into three groups orientated NE-SW and extending over 250m. Stones with cupmarks and cup-and-ring decorations include Stones B, F and L. |

|||

Temple Wood (TW) |

228 |

Stone Circle Group |

NR 826 978 |

Rock Art: Two stone circles are located south of Nether Largie. SW circle contains two monoliths with decoration; one of these is centrally located. Motifs include faint concentric circles, a conjoined double spiral extending over two faces, and a curious three-strand ornament that forms a single spiral. Cupmarks are also present. |

|||

Torbhlaran |

229 |

Standing Stone |

NR 863 944 |

Rock Art: Single monolith with SW face containing up to 30 cupmarks on the lower section, and a further nine on its NE face. |

|||

Torran |

230 |

Standing Stone |

NM 878 048 |

Rock Art: Single monolith with probable pecked Christian crosses on both faces. |

|||

Dunadd |

248 |

Later prehistoric fort and medieval settlement (once surrounded by water) |

NR 837 935 |

Rock Art: Series of engraved linear marks around the ring fort section (citadel) of the site. Discovered through excavation, was an engraved piece of slate with Pictish symbols that included a bird, several intricate rosette motifs and cervids (probably a male and female red deer), Found within the Upper Ridge Fort area of the site. |

|||

An inventory of free-standing monument rock art sites within the Kilmartin Valley (adapted from RCAHMS 2008)

Site Name |

RCAHMS No. |

Monument Type |

Grid Ref. |

Rock Art |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Carn Bàn |

36 |

Cairn |

NR 840 907 |

Pecked multiple lozenges on one face and recent chiselled marks on rear of large stone. |

Glennan |

58 |

Cairn |

NM 856 011 |

Two cairns, with the northern cairn possessing a covering slab containing at least nine cupmarks. |

Nether Largie Mid |

67 |

Cairn |

NR 830 983 |

Large circular multi-cisted-cairn located on a low gravel terrace. This monument is now much denuded. The covering slab from one cist contains a single cupmark and an axe motif. |

Nether Largie North (NLN) |

68 |

Cairn |

NR 830 094 |

Three stones including a large covering slab (underside), cist wall and stone fragment. Rock art from these stones includes a series of axes, circles and cupmarks. |

Ri Cruin (RC) |

76 |

Cairn |

NR 825 971 |

Decorated east wall slab comprising multiple axe motifs and a linear barb, interpreted as a halberd (see Needham, Cowie & McGibbon 2012) but more likely to be a stylised boat. |

Badden |

81 |

Cist |

NM 858 890 |

Side slab, discovered during ploughing and containing multiple double and triple-lined lozenges, enclosed in a rectilinear rebate. |

Dunchraigaig Cairn |

48 |

Later prehistoric cairn with a central and larger SE cist |

NR 833 968 |

The site was excavated in 1868 by Greenwell. Found in 2021 was an engraved panel featuring five cervids, two of which are red deer stags. The underside panel formed part of a large capstone covering the SE cist. |

Killbride |

98 |

Cist |

NE 838 077 |

A severely ruined cist was discovered in 1982 with one of the side slabs containing three roughly- pecked triangular motifs. |

Ballymeanoch |

199 |

Standing Stone group (Stones A to G) |

NE 833 964 |

Standing stone group located close to the Ballymeanoch Henge. Originally seven stones, now six remain. Two stones are decorated with multiple cupmarks, concentric circles and cup-and-rings, several with a single grooved line. From the same group, an excavated stone (Stone G) contained an hourglass perforation and cutmarks. |

Nether Largie Group |

222 |

Standing Stone group (Stones A to N) |

NR 828 976 |

Standing stone cluster, organised into three groups orientated NE-SW and extending over 250m. Stones with cupmarks and cup-and-ring decorations include Stones B, F and L. |

Temple Wood (TW) |

228 |

Stone Circle Group |

NR 826 978 |

Two stone circles are located south of Nether Largie. SW circle contains two monoliths with decoration; one of these is centrally located. Motifs include faint concentric circles, a conjoined double spiral extending over two faces, and a curious three-strand ornament that forms a single spiral. Cupmarks are also present. |

Torbhlaran |

229 |

Standing Stone |

NR 863 944 |

Single monolith with SW face containing up to 30 cupmarks on the lower section, and a further nine on its NE face. |

Torran |

230 |

Standing Stone |

NM 878 048 |

Single monolith with probable pecked Christian crosses on both faces. |

Dunadd |

248 |

Later prehistoric fort and medieval settlement (once surrounded by water) |

NR 837 935 |

Series of engraved linear marks around the ring fort section (citadel) of the site. Discovered through excavation, was an engraved piece of slate with Pictish symbols that included a bird, several intricate rosette motifs and cervids (probably a male and female red deer), Found within the Upper Ridge Fort area of the site. |

Accompanying cairns and cists is a series of landscape monuments that include standing stones that are sometimes arranged in rows and groups, and a number of open-air rock panels. Each of these groups appears to be deliberately distributed in such a way as to suggest an association between cairns and a defined ritualised landscape; the standing stones possibly forming a series of procession markers that were visible across wide tracts of landscape (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). Although many stones are undecorated, there is a small assemblage that contains multiple cupmarks and cup-and-rings and is arranged in complex design fields (e.g., Figure 6). The same motifs engraved onto the standing stones are also present on the open-air rock outcropping. The functionality of standing stones within this landscape is unclear, although there are a number of patterns emerging that could suggest monument clustering, orientation and an association with cairns and cists (e.g., Bradley 1993, 2009; Bradley et al. 2011). In Wales, the author has suggested that standing stones may represent some form of processional marker, whereby the dead and their respective communities were obliged to walk through a landscape in a particular way (Nash 2007). The rock art present in this group of monuments appears to be orientated in a particular way, suggesting a deliberately chosen pattern or alignment. It is probable that, given the linearity of many standing stone groups within the valley and their spatial relationship with, in particular, cists (rather than any other monument type) that both monument groups are contemporary. However, the author expresses caution with this interpretation in that both standing stones and cists also stand close to other monument groups as well and that the distribution pattern may be far more complex than previously considered.

The monolith group of Ballymeanoch (Stones A, B, C & D) and the single monoliths of Stone F (Nether Largie) and Torbhlaran.

(Clockwise) Figure 7. The landscape vista belonging to the Nether Largie North monument. Figure 8. One of two rectangular stone-lined chambers within the Ri Cruin monument. Figure 9. The Temple Wood Stone Circle central cist.

Within these sections of the valley are a number of free-standing monuments that contain engraved rock art including the three Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age cairns of Nether Largie North (Figure 7), Ri Cruin (Figure 8) and Temple Wood (Figure 9); these three are by far the best preserved and most impressive of the Kilmartin Valley stone monument group.

Cupmarks and weaponry, located on the covering slab of Nether Largie North (after RCAHMS 2008, 33).

Similarly, at the nearby reconstructed Ri Cruin cairn, one of the stone-lined cists contains a series of axe engravings on an end slab (Figure 13). The three cists - one located within the north-western section of the cairn, the other two in the south - are largely intact, although all were emptied in recent times. The western end slab belonging to the far southern cist contains seven pecked axes. A further decorated slab from the same cist possesses a vertical grooved line with up to ten shorter horizontal lines extending from the right-hand side (described as a 'rake' design). The engraving was thought to represent a stylised boat with an accompanying crew or a halberd with a beribboned haft (RCAHMS 2008, 36). This slab (or pillar) was removed from the cist but was later destroyed in a fire at nearby Poltalloch House; however, an all-important cast was made of this stone prior to the destruction of the stone. Needham et al. (2012, 89-110) have undertaken a detailed study of this cast (sometimes referred to as the Halberd Pillar) and have concluded that the engraving is that of a halberd and that it may have originated from another site. However, I am more inclined to suggest that the engraving represents a Bronze Age boat. My assumption is based on a number of similarly designed engraved and painted boats that are found on open-air rock art panels in Southern Scandinavia (e.g., Cullberg 1975).

End slab within the southern cist of Ri Cruin, decorated with six axes (after RCAHMS 2008, 35).

The majority of the engraved rock art assemblage within the Kilmartin Valley free-standing monuments is what O'Kelly (1982) considers curvilinear forms. Although this assemblage is relatively small compared with other areas of northern Britain, the motif types are limited to four generic types: concentric circles, cupmarks, lines and spirals. In complete contrast to the curvilinear designs used in the majority of the Kilmartin Valley free-standing monuments are the geometric designs that are present on the underside of a stone covering slab made from schist and belonging to a former cist at Badden (Figure 15). This slab, first reported by J.G. Scott in 1960, has a rectangular engraved rebate which would have produced a tight fit between the slab and the stone cist. Across half of the underside of the covering slab is a set of interconnecting five double and eight triple lozenge motifs, several of which extend beyond the rebates. Each lozenge contains a small dot or cupmark. The design field of the Badden covering slab has parallels with nearby Carn Bàn and monuments that occupy the Boyne Valley, in particular, the passage grave of Fourknocks (Figure 16).

A centrally erected monolith within the SW circle of the Temple Wood complex, decorated with engraved conjoined spirals.

Based on motif analogy, the rock art is probably Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age in date, although one could extend the tradition to between the 4th and 1st millennium BCE, especially if one is also to include Pictish motifs (see Table 1).

The rock art of the Kilmartin Valley forms part of a package of ideas that also includes distinct architectural hybrid traits such as Early Bronze Age-style rectangular stone cists within a Neolithic mound. It is more than likely that a Neolithic cult existed that used architecture, art, and landscape as means of self and community identity for a considerable time span. Moreover, and based on the distribution, certain motifs used in Neolithic/Early Bronze Age free-standing monuments began to be used within open-air panels; however, it is unclear if motifs - such as cupmarks, cup-and-rings and axes - possessed the same meaning over this period of transition, especially when one considers the complex chronological and regional changes associated with burial practice across northern Europe at this time (Bradley 2009). Throughout this period, which incidentally accounts for at least 80-90 generations of community, certain engraved motifs appear to have been a binding factor between people using the four monument types: chambered and non-chambered monuments, landscape monuments and open-air panels. It is probable that at some time during later prehistory, the complex panel narratives from each monument type established a collective artistic grammar. The rock art present on the cairns of Carn Bàn, Nether Largie North, Ri Cruin, Dunchraigaig Cairn (NGR NR 833 968) and Temple Wood (NGR NR 826 978), and the destroyed cist site at Badden represent a small percentage of the free-standing Later prehistoric monuments within the Kilmartin Valley and it could be that the rock art comes at a time when the megalithic landscape is being replaced by a ritual ideology that is markedly more subtle and private. However, I would stress that the targeted dating of engraved rock art is still problematic. Although the cupmarks present in and around the Nether Largie group, and the Ri Cruin and Temple Wood monuments are difficult to date, the engraved flat-butted axes do suggest an Early Bronze Age date of between 1800 and 1600 BCE. Similar engraved axe styles are found on eleven stones at Stonehenge and indicate a warrior-based society that is also evident throughout most of Western Europe, their presence indicating an Early to Middle Bronze Age date (Nash 2011).

Tantalising (but at the same time problematic) is the recent discovery by Hamish Fenton of Bournemouth University of engraved red deer imagery on the underside of a capstone that is incorporated into Dunchraigaig Cairn (Figure 17). The engraved images, found on the underside of one of two capstones, comprised five cervids - probably red deer (Cervus elaphus), two of which were stags - each with a pronounced fully-grown antler set. It is considered that these engravings date to the fourth millennium BCE and are therefore contemporary with (maybe) the construction and use of the monument (see Valdez-Tullett et al. 2022). As far as I am aware, this is one of the earliest figurative rock art panels from this period in the British Isles. In a European context, such figurative engravings could represent an engraving activity span of at least three millennia.

Tipping's summary charting the prehistoric activity in and around the Kilmartin Valley is chronologically set out, with the earliest presence occurring during the Mesolithic and extending through the Neolithic and Bronze Age periods [and beyond] (RCAHMS 2008, 1-17). Muc of this chronology fits comfortably into a wider European framework (Cooney 2000; Cunliffe 2004; and Waddell 2005, for example). However, in terms of the longevity of use for each monument group, the picture is more confusing and less chronologically ordered. There may have been a time span when probably all monument groups were in use, or at least were recognised and respected; the earlier monuments, such as the long and round cairns of the Clyde Group. This monument group formed an established ancestral history that would have extended over a thousand years or more (Scott 1969, 218-9). Similarly, and based on archaeological evidence, a number of cairns show evidence of chronological phasing, suggesting that the longevity of use in certain monuments may have extended over many hundreds of years. In addition to architectural style, several burial traditions are recognised - inhumation and cremation internments - which again suggests a long-term burial practice in operation. In terms of rock art and its distribution, all free-standing monument groups have a limited representation and, in many respects, reflect a similar pattern to the distribution of Atlantic-style rock art found in the burial monuments of Ireland and North Wales (Waddell 2005; Nash 2007; Sharkey 2004). The (sometimes) sporadic and limited distribution of engraved rock art could well be a later introduction to already-established monuments such as the cairns and cists. Alternatively, the introduction of these new architectural forms may have also included the commission of engraved rock art as well. It is more than probable that the engraved Atlantic-style rock art present on free-standing monuments is contemporary with the large number of open-air sites that are found within the valley; many of these are sited close to cairns and cists, suggesting a synergy between monument, art and landscape.

The Dunchraigaig Cairn, where the figurative rock art is present on the underside of the capstone.

It is hoped that from the Motifs and Monuments Project and ScRAP that a greater understanding of how certain motifs were used, and their spatial patterning will stimulate further debate on the intentionality of these most enigmatic and widely used engraved motifs and their relationship between monuments and the watery landscapes in which they once stood.

The author would like to thank Gerhard Milstreu for the invitation to write the initial text, and to Abby George and Helena Hepburn who kindly read through it and sorted out my usual deficiencies in grammar and spelling. To Caroline Malim who at very short notice produced the Kilmartin Valley map (Figure 3). Finally, my sincere thanks to Peter Robinson and Ben Dickins of the Bradshaw Foundation, who encouraged me to rewrite and publish through this website. All mistakes are my own responsibility.

Barnett, T., Valdez-Tullett, J., Bjerketvedt, L.M., Alexander, F., Jeffrey, S., Robin, G. and Hoole, M., 2021. Prehistoric Rock Art in Scotland: Archaeology, Meaning and Engagement. Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland.

Beckinsall, S., 1999. British Prehistoric Rock Art. Stroud: Tempus.

Bradley, R., 1993. Altering the Earth, The 1992 Rhind Lectures, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Monograph Series No. 8.

Bradley, R., 1997. Rock Art and the Prehistory of Atlantic Europe. Signing the Land. London: Routledge.

Bradley, R., 2009. Image and audience: rethinking prehistoric art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bradley, R., Phillips, T., Richards, C., and Webb, M., 2001. Decorating the houses of the dead: incised and pecked motifs in Orkney chambered tombs. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 11: 45-67.

Campbell, M. and Sandeman, M.L.S., 1962. Mid-Argyll: a field survey of the historic and prehistoric monuments. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 95 (1961-2): 1-125.

Cooney, G., 2000. Landscapes of Neolithic Ireland. London: Routledge.

Cullberg, K., Nordbladh, J. & Sjöberg, J,. 1975. Hällmalningen i Tumlehed, Särtryck ur Fynd rapporter 1975: Rapporter över Göteborgs Arkeologiska Musei undersökningar.

Cunliffe, B., 2004. Facing the ocean: The Atlantic and its peoples, 8,000 BC to AD 1500. London: Oxford University Press.

Currie, A., 1830. A Description of the Antiquities and Scenery of the Parish of North Knapdale, Argyleshire, by Archibald Currie. Glasgow: W.R. M’Phun.

Eogan, G., 1986. Knowth and the passage-tombs of Ireland. Thames and Hudson, London.

Forde-Johnson, J. L., 1956. The Calderstones, Liverpool. In T. G. Powell, T. and G. E. Daniel (eds.), Barclodiad y Gawres: the excavation of a megalithic chambered tomb in Anglesey. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 73—5.

Freedman, D. 2011. Kilmartin in context I: Kilmartin and the rock art of prehistoric Scotland. In A.M. Jones, D. Freedman, B. O’Connor, H. Lamdin-Whymark, R. Tipping and A. Watson (eds) An Animate Landscape: Rock art and the prehistory of Kilmartin, Argyll, Scotland. Oxford: Windgather Press, 282-311.

Herity M., 1970. The early prehistoric period around the Irish Sea, in D. Moore (ed.) The Irish Sea Province in Archaeology and History, Cambrian Archaeological Association, pp. 29—37.

Lynch, F. M., 1970. Prehistoric Anglesey. Anglesey Antiquarian Society.

Mazel, A., Nash, G.H. and Waddington, C., (eds.) 2007. Metaphor as Art: The Prehistoric Rock art of Britain. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Jones, A.M. 2006. Animated images: images, agency and landscape in Kilmartin Argyll, Scotland. Journal of Material Culture 11: 211-25.

Jones, A.M. 2007. Memory and Material Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jones, A.M., Freedman, D., O’Connor, B., Lamdin-Whymark, H., Tipping, R. and Watson, A., 2011. An Animate Landscape: Rock art and the prehistory of Kilmartin, Argyll, Scotland. Oxford: Windgather Press.

Jones, A.M., 2012. Living rocks: animacy, performance and the rock art of the Kilmartin region, Argyll, Scotland. In A. Cochrane & A. Meirion Jones (eds.) Visualising the Neolithic. Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Papers 13, Oxbow Books, pp. 79-88.

Mazel, A., Waddington, C. & Nash, G.H., 2007. Art as Metaphor: The Rock art of Britain. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Mazel, A. & Nash, G.H., 2022. Signalling and Performance: Ancient Rock Art in Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Morris, R.W.B., 1973. Prehistoric Petroglyphs of Southern Scotland. In Bollettino di Studi Prehistorici, 10.

Morris, R.W.B., 1977. The Prehistoric Rock art of Argyll. Poole: Dolphin Press.

Nash, G.H., 2007. Fire at the end of the tunnel: How megalithic art was viewed. In D. Gheorghiu & G.H. Nash (eds.) The Archaeology of Fire: Understanding Fire as Material Culture. Budapest: Archaeolingua, pp. 117—52.

Nash, G.H., 2011. Rare examples of British Neolithic and Bronze Age human representations in rock-art: Expressions in weapons and warriorship. Fundham Mentos IX, Global Rock Art. Brazil. Volume III, pp. 845-58.

Nash, G.H., 2012. Pictorial signatures with universal meaning or just coincidence: a case for the megalithic art repertoire of Mediterranean and Atlantic sea-board Europe. In J. McDonald & P. Veth (eds.) A Companion to Rock Art. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing (Series: Blackwell Companions to Anthropology), pp. 127-42.

Nash, G.H., 2015. Between water and monument: The Atlantic rock art of the Kilmartin Valley. Adoranten 2015, pp. 104-115.

Needham, S., Cowie, T. & McGibbon, F., 2012. The halbberd pillar at Ri Cruin cairn, Kilmartin, Argyll. In A. Cochrane & A. Meirion Jones (eds.) Visualising the Neolithic. Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Papers 13, Oxbow Books, pp. 89-110.

O’Kelly, M. J., 1982. Newgrange: archaeology, art and legend. London: Thames and Hudson.

O’Sullivan, M., 1986. Approaches to passage tomb art. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 116: 68—83.

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, 2008. Kilmartin: An Inventory of the Monuments extracted from Argyll (Volume 6).

Scott, J.G., 1969. The Clyde Cairns of Scotland. In T.G.E Powell, J.X.W.P. Corcoran, F. Lynch & J.G. Scott (eds.) Megalithic Enquiries in the West of Britain. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Shee-Twohig, E., 1981. Megalithic art of Western Europe. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Sharkey, J., 2004. The meeting of the tracks: rock art in ancient Wales, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch.

Sharpe, K.E., 2007. Rock-Art and Rough Outs: Exploring the sacred and social dimensions of prehistoric carvings at Copt Howe, Cumbria. In A. Mazel, G.H. Nash and C. Waddington (eds.) Metaphor as Art: The Prehistoric Rock art of Britain. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 151—73.

Simpson, J.Y., 1867. Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc. upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and Other Countries. Edinburgh: Reprinted by Kessinger Publishing Legacy Reprints.

Tilley, C. 1991. Constructing a ritual landscape. In Regions and Reflections (in honour of Marta Stromberg). K. Jennbert, L. Larsson, R. Petre & B. Wyszomirska-Werbart (eds.) Acta Archaeologica Lundensia Series 8, No. 20: 67—79.

Tipping, R., 2008. Introduction: Kilmartin Valley Landforms and Landscape Evolution. In Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, 2008. Kilmartin: An Inventory of the Monuments extracted from Argyll (Volume 6), pp. 1—17.

Valdez-Tullett, J. 2019. Design and Connectivity: The case of Atlantic rock art. BAR International Series 2932. Archaeology of Prehistoric Art 1. Oxford: BAR Publishing.

Valdez-Tullett, J., Barnett, T., Robin, G., & Jeffrey, S., 2022. Revealing the Earliest Animal Engravings in Scotland: The Dunchraigaig Deer, Kilmartin. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1-27. doi:10.1017/S0959774322000312

Waddell, J., 2005. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland, Wordwell Bray.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation