Ismo Luukkonen is a photographer living and working in Turku, Finland. For twenty years he has specialized on photographing rock art and other prehistoric sites, mainly in Finland and Scandinavia. In his work the documentary approach to ancient images and landscapes is joined with thoughts on time, momentariness and eternity. Ismo Luukkonen also works as a senior lecturer of photography in the Arts Academy at the Turku University of Applied Sciences.

Some 13,000 years ago the ice that covered the area of present Finland started to melt. About 1,500 years later even the most northern corner of the country was free of ice, and soon after that the first humans - mesolithic hunter-gatherers - arrived in this region.

Roughly 7,000 years ago central and south-eastern Finland was an area of dense forest with thousands of lakes. Labyrinthine waterways provided routes through the northern wilderness. The forests and lakes offered a way of life for groups of people. They hunted seals, Eurasian elks and waterfowl, they fished and they gathered. At that time new ideas reached the northern population, ceramics being one example. Fragments of large pots decorated with a comb-like tool are typical artefacts found in the settlements of this time - 7,100 to 4,000 years ago in eastern Finland - a period known today as the Pit-Comb Ware Culture. Some traces of early agriculture have been found from this period, but it did not become common until later in the Stone Age. This is why the era is also called 'subneolithic'.

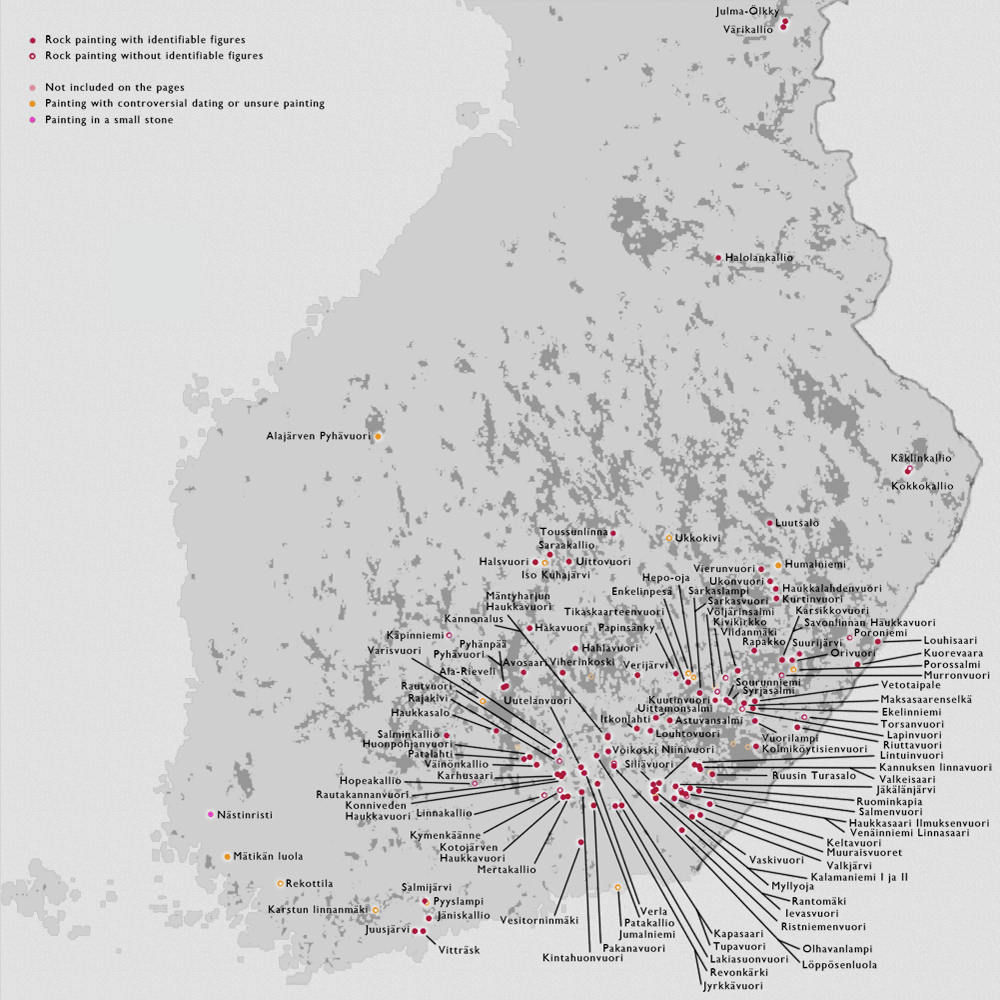

The most apparent legacy of the Pit-Comb Ware people in today's landscape is the rock art. There are over 100 sites with identifiable figures and up to 30 sites with patches of colour that have currently been recorded in Finland. The typical rock painting sites are vertical cliffs rising from the lakes, or large glacial erratics situated close to the shoreline. Often an overhang above the paintings provides extra shelter for the fragile images.

Today some of the rock paintings are several meters above the waterline. The water level has changed during the past millenia due to the post-glacial rebound; the rise of land masses that were depressed by the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, through a process known as isostasy. In many lake systems this caused flooding, until the waters broke new routes, leading to rapid changes in water level. A good example is the formation of the Vuoksi River about 6,000 years ago, when the waters of the lake Saimaa created a new route to the lake Ladoga. These changes have been used to date the rock paintings and other prehistoric remains. According to the most recent datings the paintings were made between 7,000 and 3,500 years ago (Seitsonen 2005).

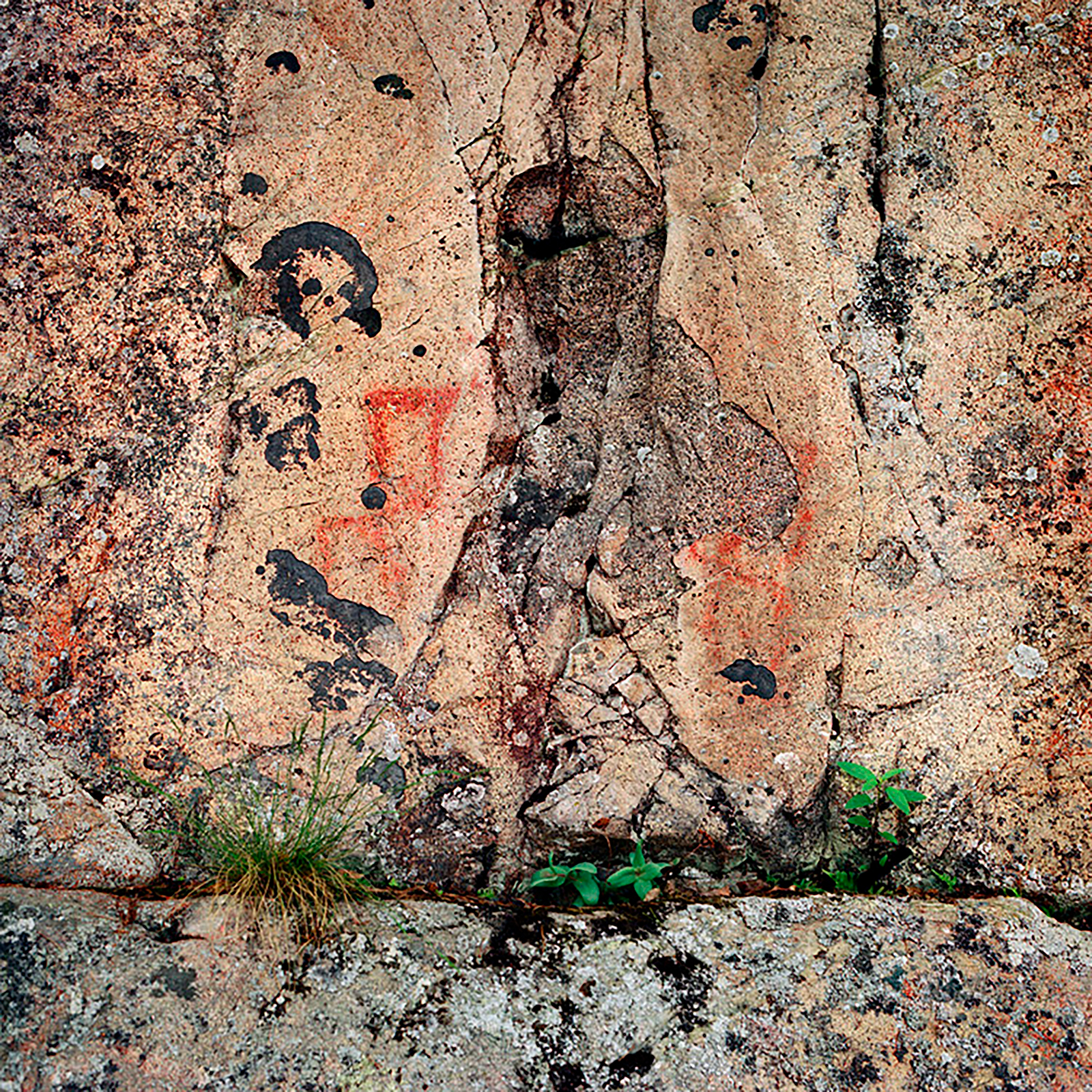

All known prehistoric paintings in Finland are made with red ochre, a colour that is easily available and permanent. Of course the colour is often faded, blurred and covered with lichen, but still the ancient images resist the detrition of time. Compared to the other type of prehistoric rock art - rock carvings - the paintings are more fragile and fewer of them have survived over time. While a rock carving site may include thousands of images, the amount of images in rock painting sites is considerably smaller. However, no Stone Age rock carvings have been found in Finland, even though large carved panels are found in neighboring countries. (Gjerde 2010) In southern and eastern Finland there is a large number of cup stones, but they are dated to the late Iron Age or even historic times.

The majority of the Finnish rock painting sites are modest in appearance. They usually contain less than ten figures, or just a smear of red colour. However three sites are specific by their extent and number of images:

Saraakallio in Laukaa is an adventure of more than 100 figures, many of which are peculiar among the imagery of northern rock art.

Astuvansalmi in Mikkeli, with about 70 figures, is the best known example of Finnish rock art. It is remarkable by its large and clear figures as well as its well preserved environment.

Varikallio, situated far to the north in Suomussalmi also has about 70 figures, some of which have an expressive power rare in the northern rock art.

Saraakallio, Astuvansalmi and Varikallio are considered as important 'cult places' where people gathered regularly for thousands of years. But it is not merely the size of the painted panels or the number of figures that make the sites important and specific; the interaction between the ancient paintings and the archetypal environment gives a special feeling to these rock painting sites. They are places where it is possible to sense the presence of an ancient people, both in the marks on the rock and in the environment itself. It seems the rock paintings make the span of time tangible, but in a way where time takes on a different meaning.

The Finnish rock paintings were forgotten for thousands of years. The first one was found in Kirkkonummi in 1911 by the composer Jean Sibelius, but more than fifty years passed before the next discovery. The majority of the rock art sites have been found only in the last 40 years. And new sites are still being found.

About 750 individual images can be counted on the 100 or so Finnish rock painting sites known today. The motifs are bound to the life and beliefs of the Pit-Comb Ware hunter-gatherers. There are no domestic animals and no images relating to agriculture.

Cervids

Cervids (216) are often the most important figures in the sites. They are depicted in different styles. The largest ones are painted with an outline (72). The outline of the painted animals is often quite naturalistic and they can be identified as Eurasian elks (Alces alces). At times the heart is marked inside the body. Ears are often clearly shaped, but no antlers are depicted. In relation to the waterline the big elks are usually higher on the cliff than the smaller animals. This suggests they are also probably older than the smaller ones (Seitsonen 2005) A number of cervids are fully painted (52), but they are usually smaller than the outline-painted cervids. The smallest cervids are painted with a single line (92). It is difficult to identify weather these are elks or deer.

Humans

Humans (257) are the most common figures in Finnish rock paintings. The depiction is typically a simple, frontal figure, standing in a symmetrical position. The legs and arms are often bent. Only in a few cases can the gender of the human be identified. The head is usually marked with a spot with no details, but there are some horned humans and some with a circular or triangular head with eyes and a nose. In some sites such as Saraakallio, there is a number of humans depicted in profile.

Boats

Boats (87) are depicted with a horizontal, slightly curved line with short vertical lines representing the crew. They often appear as pairs. Some boats seem to have a head of an elk in the prow. In Saraakallio and Avosaari there are detailed boats that also seem to depict a swimming elk.

Other animals

Other animals (75) include mainly snakes (29) and fish (17). In many cases it is quite difficult to identify the exact species. Snakes often appear together with a human. Birds are recognized in one site only - the waterfowl of Rapakko.

Geometric forms

Geometric forms (61) include mainly crosses (14) and groups of lines (21), but there are also some more complex forms. The most specific forms are the net figures in Vittrask.

Hand prints

Hand prints (43) can be identified in at least ten sites. They are made by pressing the hand with colour onto the rock. However, it is possible that this motif is much more common; in many sites there are patches that are about the size of a hand, but cannot be recognized by the shape. Also, in many cases there are large areas of red paint on the rock. Maybe they are composed by dozens of handprints. What if creating a clear mark has not been the main purpose, but the touch? Touching the rock with a painted hand over and over again could explain these nonfigurative red paintings.

What did the Pit-Comb Ware people think when they painted images on rock walls? No original tradition concerning the rock paintings has survived over the past millennia. To find answers, we have to look at the paintings, their imagery and environment, and compare this to what we know about the life of northern hunter-gatherers. Different interpretations on Finnish rock art have been presented by the researchers during the past fifty years. The common idea is that the images are related to the beliefs and the worldview of subneolithic people. The earlier interpretations were based on hunting magic or totemism. The most recent interpretations are based on the studies of shamanism among the northern native people. This, in many cases, seems to give the most promising context to the world depicted in rock paintings. (Lahelma 2008)

The elk has a special status in rock art as it has in the tradition of northern native people. In rock paintings the elk appears side by side with humans, and it is not shown as a hunted animal. Actually, there are no hunting scenes in Finnish rock paintings, and images of an important prey, the seal, are not found painted on Finnish rocks. The painted elk seems to have an importance other than the supply of food. In Sami tales the elk was a helper of the shaman, like-wise the snake, another animal that is repeatedly painted on cliffs.

There are also images that seem to depict a metamorphosis or the act of falling into trance. In the Kolmikoytisienvuori rock painting in Ruokolahti there is a human with a snake-like lower body. In the Mertakallio rock painting in Iitti there is a depiction of a floating human and a snake. The snake in both cases can be seen as a spirit helper of the shaman.

But the interpretations based on shamanism cannot explain everything. Thanks to the recent studies by Antti Lahelma, Timo Miettinen, Pekka Kivikas et al we have a clearer idea about what the painters had in their minds, although the rock paintings still manage to keep their mysteries. They tempt us, tease us with simple likenesses and after a closer look hide behind the curtain of time. It is like reading a book written on a language we almost know.

The rock paintings are fragile. It is astonishing that they have survived over time in the open on cliffs and boulders. No doubt many paintings have been destroyed by the harsh climate and invading vegetation. Many of the paintings that remain are fragmentary and difficult to interpret. But still they carry meanings. In addition to searching for the original meanings of these prehistoric rock paintings, we can also ask another question: What is the meaning and relevance of prehistoric rock art to us today?

Even though we do not exactly know what the artists meant when they painted the images on the cliffs, we can still recognize something - something more than just the painted motifs. Even though we do not understand the language, we can recognize the will to create an image. We can see the result of that will to create on the cliff. This is something, I believe, many can identify with. We still want to create and share images, leave a mark, tell about our thoughts, lives and beliefs, as did the people 7,000 years ago. The languages and tools are different, but the will is common. Can we see the continuation from the ritualistic act of painting rock walls to the act of sharing images on the walls of social media?

The concept of time has great significance when thinking about today's meaning of rock art. The knowledge that the paintings are made thousands of years ago affects the way we see and think about the images. Rock paintings have a special aura, a sense of authenticity. They are touchable, but still distant. It is not possible to make a new painting with similar meanings. Even the most detailed copy lacks the authenticity and cannot create such meaning. A copy is not part of the history of the environment like the original. A copy does not carry all the sunrises the original has felt. At least, not until after some thousands of years.

The rock paintings are authentic signs of the Stone Age people. Not only iconic signs that resemble the elks or humans depicted, but indexical signs that are connected by a touch to the people that created them. Like a smoke is a sign of a fire or a stain of jam on the fridge door is a sign of a child. Even though the smoke does not look like the fire, the stain does not look like the child or the painting does not - necessarily - look like the painter. The painting means that someone, some thousands of years ago stood there, touched the rock and created an image on the stone wall.

By the painting, I can see the image, feel the presence of the people that painted the sign. It feels that the distance created by the time narrows and I can hear their voices in my ears.

When I look over the shoulder I can see the disappearing line of past generations. Seven thousand years is eternity in the human experience, but still only a moment in time.

- Gjerde, Jan Magnus 2010. Rock art and Landscapes. Studies of Stone Age rock art from Northern Fennoscandia. Unpublished dissertation for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor. University of Tromso. http://munin.uit.no/handle/10037/2741

- Kivikas, Pekka 2005. Kallio, maisema ja kalliomaalaus. Rocks, Landscapes and Rock Paintings. Jyvaskyla: Minerva.

- Lahelma, Antti 2008. A Touch of Red. Archaeological and Ethnographic Approaches to Interpreting Finnish Rock Art. Iskos 15. Helsinki: The Finnish Antiquarian Society. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/19406

- Seitsonen, Oula 2005. Shoreline displacement chronology of rock paintings at lake Saimaa eastern Finland. Before farming 2005/1.

→ Finnish rock paintings: www.ismoluukkonen.net/kalliotaide/suomi/index.html

→ Scandinavian rock art: www.ismoluukkonen.net/kalliotaide/piirros/index.html

→ Facebook – Rock Art Finland: www.facebook.com/pages/Rock-Art-Finland/283832885096773