by Wendy All

Volunteer, Rock Art Archive, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology

Namibia contains some of the best African rock art, and in April 2017 I visited two rock art sites. After clearing customs at Hosea Kutako International Airport, my hosts and I set out by van toward our lodgings in Windhoek, the capital of Namibia. The landscape looked remarkably like the Mojave Desert, where I participated in field surveys with Jo Anne Van Tilburg and the UCLA Rock Art Archive. Suddenly our driver skidded to a stop to allow a troop of baboons to cross the road a reminder that we were in southwestern Africa and not in California. Dramatic moments like this characterized the international rock art colloquium led by Neville Agnew of the Getty Conservation Institute., held April 21 - May 1, 2017, in Namibia. The title of the colloquium was “Art on the Rocks: A Global Heritage.” Its stated purpose was to bring attention to endangered rock art treasures, the ancient art galleries that document our human story.

Worldwide, rock art - which includes petroglyphs and pictographs, some as much as 40,000 years old (Taçon et al. 2014) - is endangered by politics and policies, the environment, lack of resources, vandalism, and ignorance. Until recently, rock art was marginalized in mainstream archaeology, partially due to the difficulty of dating petroglyphs in particular.

Paintings in caves and shelters are usually protected from the elements and often contain organic materials, allowing radiocarbon dating. Petroglyphs, pecked or carved into rock faces and often exposed to the elements, prove more challenging. Recent dating methods consider petroglyphs in context with other ethnographic evidence.

The Getty Group, as we came to be called by our Namibian hosts, was an international gathering inspired by the publication of Rock Art: A Cultural Treasure at Risk (Agnew et al. 2015). The publication identifies “four pillars of rock art conservation policy and practice”: (1) public and political awareness; (2) effective management systems; (3) physical and cultural conservation practice; and (4) community involvement and benefits. All authors of the publication were present, and each day of the colloquium was dedicated to a different pillar. These discussions alternated with visits to rock art sites. What made the gathering unique was the array of additional invited participants, including archaeologists who specialize in rock art and those with a passion to increase the public awareness and understanding of rock art.

The latter included the Bradshaw Foundation, which provides extensive online learning resources focused on ancient rock art and the artistic achievement of early humans; Martin Marquet producer of the 3D movie The Final Passage: Chauvet-Pont d’Arc Cave; Pilar Fatás Monforte director of the Altamira Cave replica; and myself, a volunteer at the UCLA Rock Art Archive since 1998. While my degrees are in linguistics and in advertising and illustration, and I make my living as a designer and writer, rock art has always had a visceral pull for me. Attending Jo Anne’s classes in 1997 through UCLA Extension was an extraordinary opportunity to learn about and document rock art in the California desert, where some petroglyphs are 8,000 years old. The experience was compelling and led to me to volunteer at the archive.

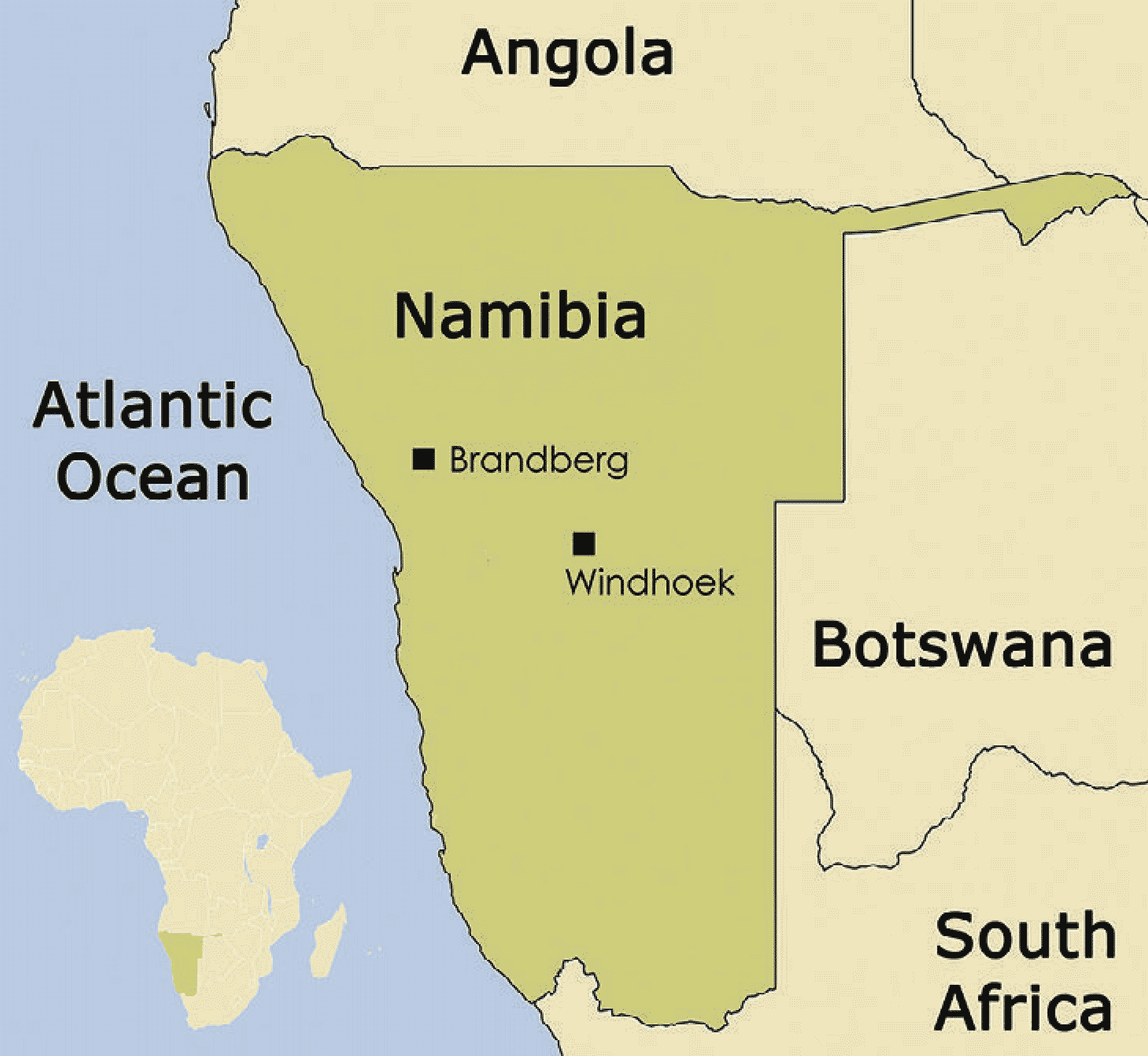

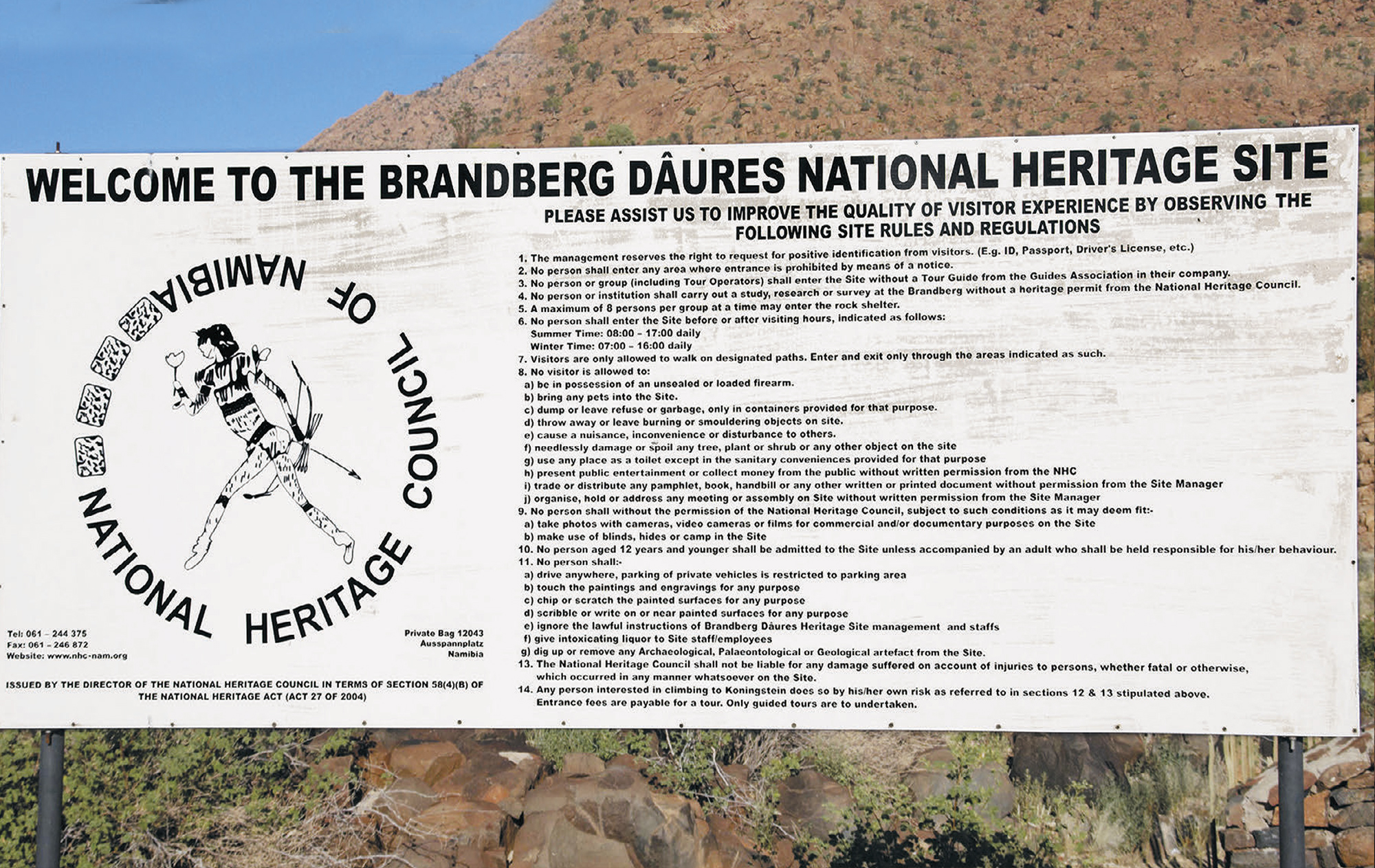

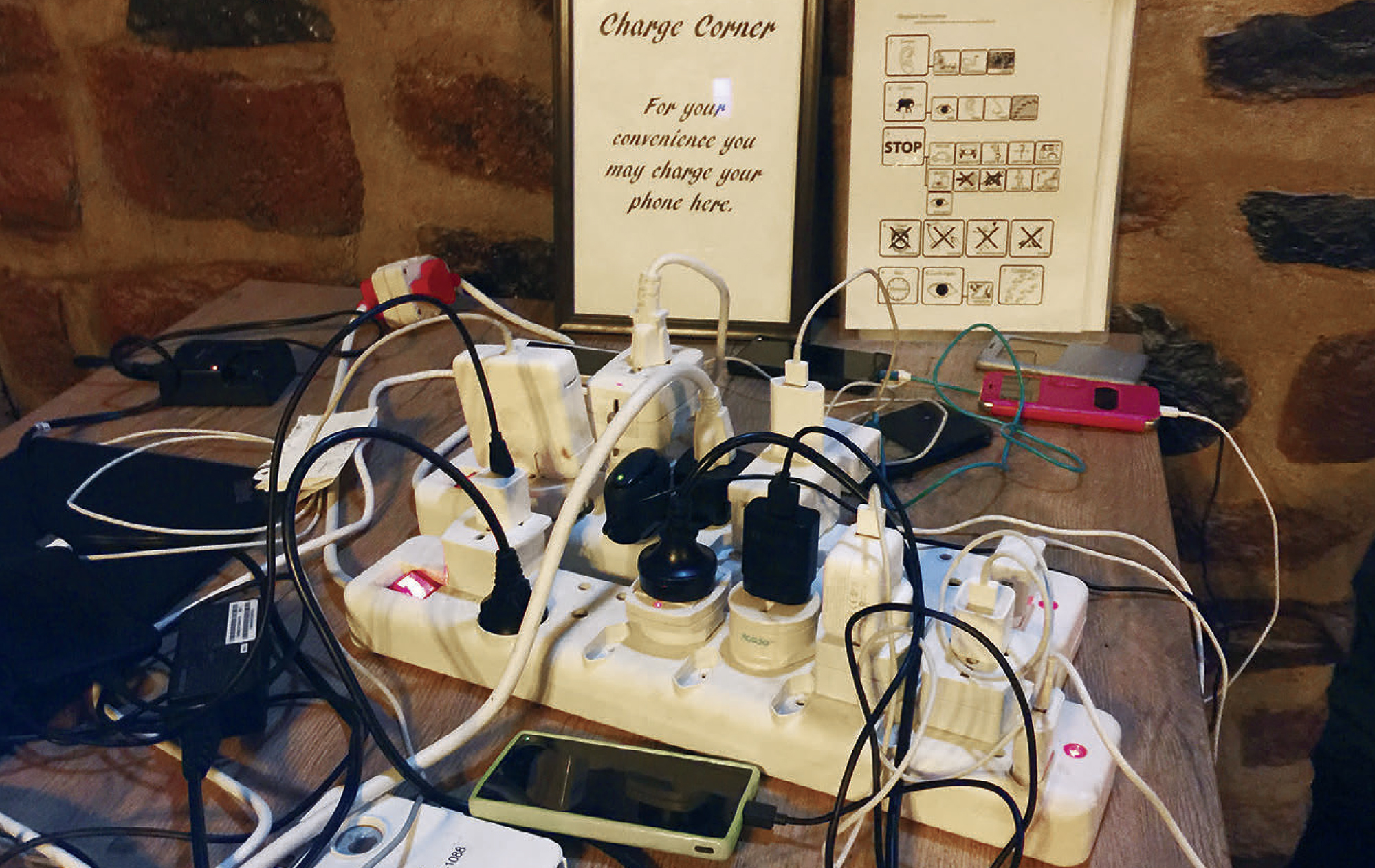

The first day of the colloquium was held in Windhoek. The next day we began our trek toward two rock art sites in the Erongo region, also known as Damaraland, about 300 km to the northwest. The Brandberg (“Burning Mountain”), named for the reflection of the sun on its pink granite surfaces, is the highest mountain in Namibia (Figure 1). Surrounded by windswept clouds, it loomed orange-violet across the Namib plain. It grew ever larger as our caravan made its way toward White Lady Lodge, whose sign proclaimed it to be “Home of the Desert Elephants.” Named for the most famous rock art site in southern Africa, the White Lady of Brandberg, the lodge is an oasis with everything except Wi-Fi. All devices had to be charged in the main lodge, which houses the only accessible source of electricity (Figure 2). The rooms and chalets are solar powered. We were disappointed to hear that elephants had been last sighted about 20 km away, but we were treated to blazing sunrises against the Brandberg, sweet-smelling mopane wood campfires, and every night the Milky Way. In this pic- turesque setting, we continued the colloquium.

Figure 1: Location of Brandberg and the White Lady of Brandberg panel entrance sign.

Figure 2: The only accessible source of electricity at the White Lady Lodge was this charging station. Everything else was solar powered.

Figure 3: Detail of the White Lady of Brandberg panel.

Figure 4: Site management at the White Lady of Brandberg site. Note the rain guard strip above and gravel below to keep dust at a minimum.

Figure 5: The dining area inside the main lodge at Twyfelfontein.

Figure 6: The author contemplates rock art at Twyfelfontein.

The day after my presentation, we visited Dâures National Heritage Site, home of the White Lady of Brandberg (Figure 3). Although the most famous African panel, likely due to its poetic name and the history of its interpretation, it is only one of many rock paintings and rockshelters in Tsisab Gorge and the upper Brandberg. Since its discovery by German topographer Reinhard Maack in 1917, it has been a source of controversy. Maack saw the White Lady pictograph as depicting “a procession of people, ani- mals and mythical creatures.” He made a sketch while noting in his diary that “the Egyptian Mediterranean style of all the figures is surprising,” a comment that sparked speculation, myth, and debate for more than half a century. In 1929 Henri Breuil, a French archaeologist specializing in Paleolithic art, saw Maack’s sketch while visiting South Africa, but he was not able to visit the panel until 1947. He made new copies of the painted images and, based on his observations, declared the central figure to be a young woman of Minoan or Cretan origin, whose presence he explained by an ancient Mediterranean visit to this region of Africa. The legend of the White Lady of Brandberg was born.

Today scholars agree that the White Lady is actually a male figure. Both Maack and Breuil failed to notice the figure’s penis. Researchers have also dismissed any European connection. The figure is now generally thought to be a San (Bushmen) painting of a young male hunter, dating back at least 2,000 years. The panel is in a secluded grotto, a 45-minute walk from the visitor’s center. Because of the heat, it is suggested that everyone carry at least a liter of water.

However, visitors are not allowed to bring bottles or backpacks into the rock shelter, which is protected by a rain drip guard and a fence (Figure 4). As late as the 1960s, visitors threw water and soft drinks on the pale images to enhance them for photographs, damaging the delicate features a further reminder of how proper site management and public awareness can make a difference.

Our Damara guide said that more than 1,000 rock shelters preserve paintings in the upper Brandberg. She had been to a number of them but knew of others only from local informants. We followed her deeper into the gorge, scrambled over boulders, and leaped across marshy growth and the fragrant evidence of elephants to view more, though none were as elaborate as the White Lady panel. Our guide led us to a rock shelter with enough room for our group of two dozen. As we took a break from the heat, to our delight she performed songs in her particular dialect of the Khoekhoegowab language, which includes four different click consonants. Her sonorant tones and clicks reverberated inside the chamber with its damp mineral smells, reinforcing the power of the area as a sacred space. She then demonstrated the different click consonants for us.

“When our babies learn to talk, they don’t use clicks until they are about two years old,” she said, “but we can understand their baby talk.”

“What if one of us tried to speak your language without the clicks?” a member of our group asked. “I would not understand you, not even like baby talk. You must use clicks.”

It was sad to leave the colorful Brandberg after our four-night stay, but we looked forward to Wi-Fi at our next destination. We drove many kilometers over washboard roads to Twyfelfontein Lodge. Twyfelfontein (“Doubtful Spring”) is a relatively new name for a very old freshwater spring, known as /Ui-//aes to the Damara people who lived there. Nestled in a cleft of a red rock outcrop, the main lodge fulfilled my fantasy of a thatched-roof African tree house, and the carving station at the dinner buffet was exotic (Figure 5).

“Is that chicken you’re carving?”

“No, it’s crocodile; tastes like chicken.” (It tasted more like swordfish to me.)

The next morning we visited Twyfelfontein, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was enlightening to compare it to the White Lady of Brandberg site. Although both had a visitor’s center made of natural materials at the entrance, the one at Twyfelfontein was designed to blend in with the landscape, as if sprouted from fertile red sandstone crossbred with iron. At the site, one of the largest collections of rock engravings or petroglyphs in Africa, unobtrusive flights of steps allow visitors to move easily among the artwork, while metal platforms afford a view of some unreachable panels. Hundreds of images are crowded together on huge boulders covering the hillside. Mingled among zoomorphic motifs and famous images such as Lion Man and Dancing Kudu are engravings of human hands, animal footprints, and entire panels of abstracts, cupules, and pictographs surviving in rock- shelters. The rock art at Twyfelfontein was produced during the dry season, when a shortage of water and food forced people to congregate near the spring. Twyfelfontein saw its greatest flowering during the last 5,000 years, a period of increasing aridity, during which hunter-gatherer communities developed and engaged in a wide range of survival strategies.

In contemplating it all, I realized how time spent with the Rock Art Archive had enhanced my appreciation (Figure 6). There is little difference between who we are today and those long-ago artists. We all want to leave our mark, to let the world know, “I was here” and “what I attempt to communicate is important.” Our guide next drew our attention to fresh elephant footprints in the red sand along the pathway—foot-prints the size of dinner plates with ridges, each with its own signature, like human fingerprints. She said the elephants had come through earlier that morn- ing. We had missed them again. Wired and tired, we returned to the lodge. Something was going on. As we entered the property, our caravan slowed to figure out why so many other vehicles were stopped, why jeeps and vans hovered, their doors and windows open. Elephants! A family of about eight adults and two calves was walking away from the main lodge, stop- ping at one point to take a dust bath. The calves flung dust over their backs and then at each other. They twirled around, almost dancing, within the safety of the herd. We threw our van door open, cameras snap- ping, zoom lenses telescoping. Our van moved as quietly as possible to follow the animals (Figure 7). The most unexpected part was their silence; these gigantic beasts moved without sound. All we heard, other than idling engines, camera clicks, and our gasps of delight, was the red dust cascading through the wind as it hit the ground. As I write about my Namibia experience, no one thing stands out, as so many moments were outstanding. To paraphrase John Steinbeck, there is something about Africa that bites deep. “It is a dream place that isn’t quite real when you are there and becomes beckoningly real after you have gone.”

Agnew, N., J. Deacon, N. Hall, T. Little, S. Sullivan, and P. S. C. Taçon. 2015. Rock Art: A Cultural Treasure at Risk. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

Pager, S. A. 1999. A Visit to the White Lady of the Brandberg. Windhoek, Namibia: Benuela Publishers.

———. 1985. A Walk through Prehistoric Twyfelfontein. Wind- hoek, Namibia: Typoprint.

Taçon, P. S. C., N. H. Tan, S. O’Connor, J. Xueping, L. Gang, D. Curnoe, D. Bulbeck, B. Hakim, I. Sumantri, H. Than, I. Sokrithy, S. Chia, K. Khun-Neay, and S. Kong. 2014. The Global Implications of the Early Surviving Rock Art of Greater Southeast Asia. Antiquity 88:1050–1064.

Van Tilburg, J. A., G. Hull, and J. C. Bretney. 2012. Rock Art at Little Lake: An Ancient Crossroads in the California Desert. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation