At this time I met J.Michael Fay who had recently returned from his Megatransect through Western Central Africa. Having just seen a documentary of his epic journey/expedition in which he draws reference to stone age cultures in this region, I enquired about the existence of rock art.

Mr Fay put me in touch with Dr Richard Oslisly, of the Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement and the Institut de Paleontologie Humaine in Paris, who has worked in this region of Africa for numerous years.

I then met Dr Oslisly at the Institut in 2002 where we agreed that a new section on Western Central Africa's rock art was important for two reasons: much of the rock art is still being discovered today, and thus further discovery and documentation is vital. Moreover, this region appears to have been a major conduit for migration over a long period of time and therefore important in understanding the overall picture of population, migration and cultural influence in Africa. The Western Central Africa section is categorized by location rather than by style or age: Gabon, Central African Republic, Cameroon and Congo.

Peter Robinson

Project Controller

Préservation et Valorisation des Patrimoines Naturels et Culturels en Afrique Centrale.

Cellule Scientifique de l'Agence Nationale des Parcs Nationaux (ANPN) et Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, UMR PALOC, IRD / MNHN

BP 20379 Libreville Gabon

Courriels: richard.oslisly@ird.fr; roslisly@parcsgabon.ga

The 5 figurines are from north-western Cameroon - Oku, Kumbo and Jakiri. Chronology - possibly 1000 to 500 years old.

This paper reports the discovery of a form of open air rock art in the upper and middle stretches of the Ogooue valley, Gabon, where it is found engraved on ovoid boulders and flat outcrops. Previously this form of art was only known from the borders of the Congo Basin: the Bidzar petroglyphs in Cameroun (Mariiac 1981:212), the Calola, Bambala and Capelo rock art assemblages in the upper valley of the Zambezi in Angola (Ervedosa 1980:445), the engraved rocks of Kwilu site in Lower Congo (Nenquin 1959), together with Mpatou, Lengo, Bambari and Bangassou sites in the Central African Republic (Bayle des Hermens 1975: 343). The Elarmekora site, Gabon, was discovered in 1987 (Oslisly 1987), at the end of a long research program on Iron Age sites in the Otoumbi region. In central Africa, a Copper Age is unknown and the Neolithic period is immediately followed by the Iron Age, about 2400-2300 years BP. Thanks to a systematic search of the paragneiss outcrops in the Ogooue river valley, many further sites have been found (see below): Epona in the Otoumbi region, Kongo Boumba and Lindili in the Lope-Okanda Reserve. We heard of the Kaya Kaya site on the upper Ogooue only twenty years after its discovery.

The Ogooue has been used as a route for trade and the movement of cultural products since the distant prehistoric past, by Stone Age hunter-gatherers, Neolithic peoples and Iron Age populations living on the river's banks (Oslisly and Peyrot 1987). Our research from 1982 to 1992 has shown that the middle stretches of the 0gooue valley were an important archaeological centre.

The Epona Site

Adjacent to a gallery forest, 3 km south of Elarmekora, are ovoid rocks bearing more than 410 rock art petroglyphs on their surfaces. These blocks of paragneiss occur in three groups on the gentle slopes of a savannah hill. Once again, single or concentric circles are the most abundant motifs (98%). Small circles appear arranged around a large circle, and sometimes concentric circles are arranged in the fashion of flower petals. Five lizard-like forms contrast with the predominant circle motifs and there is a figure resembling a throwing knife. In central Africa, the throwing knife. In central Africa, the throwing knife (single or double bladed) is the specific weapon of the Bantu populations.

The Elarmekora Site

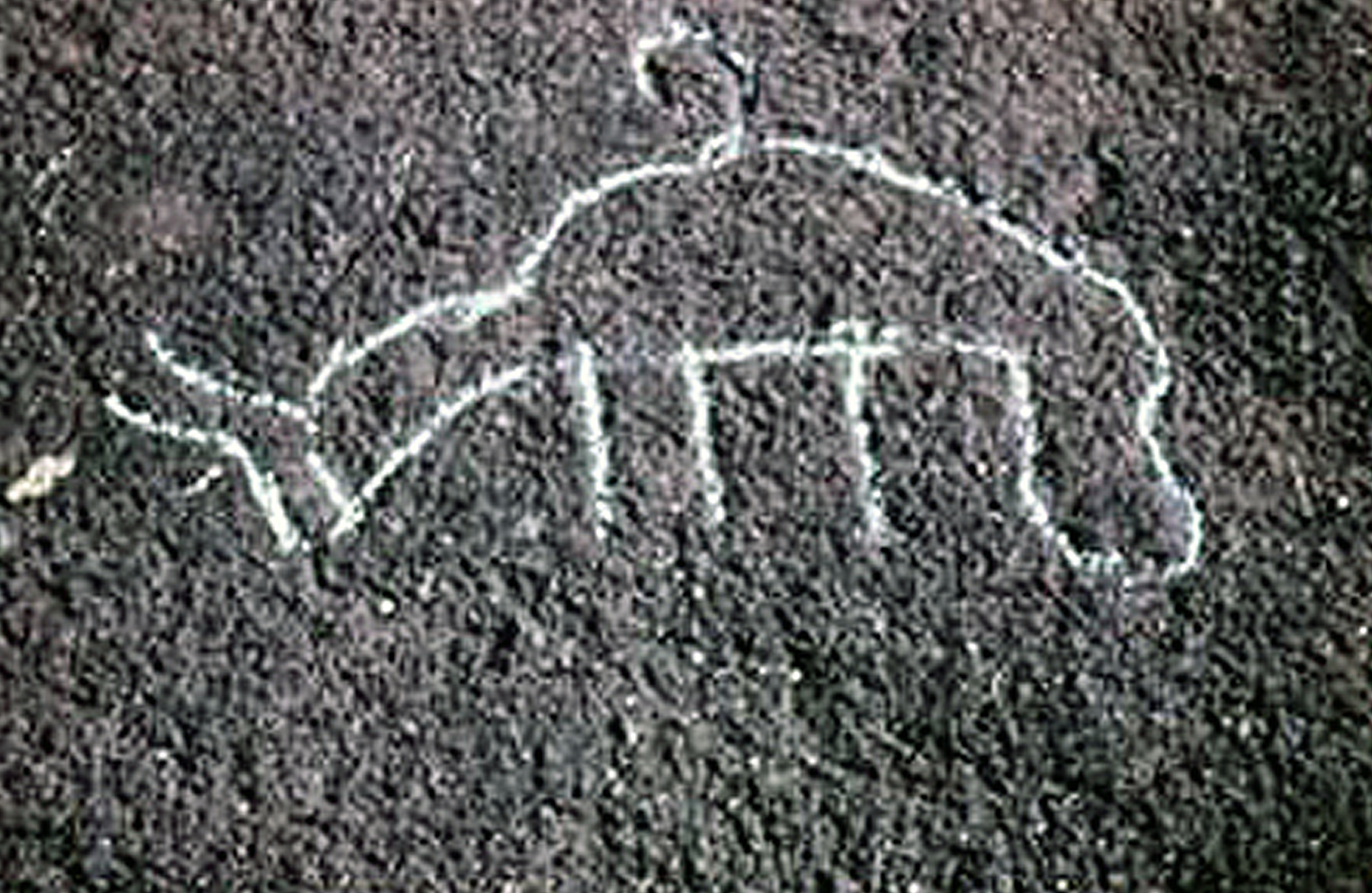

he apparent animal motifs convey an impression of an art of hunting symbolism. Most of them are associated with triangular motifs resembling projectile heads of assegai. Although no intentional layout is apparent in the location of the figures, they are grouped into five topographic zones (Oslisly 1988):

Zone A. This is the main concentration, in which more than 120 motifs have been found. Some of them occur in isolation but most belong to one of eight distinctive groups. The triangular form is the most frequent (60%), both with and without shaft (see diagram below). Animal motifs (21%) depict small quadruped animals and probably lizards. They are sometimes closely associated with triangular motifs which is suggestive of a hunting symbolism.

Zone B. This group is about 15m to the west of zone A. It consists of about 30 figures of which 53% are triangles. A dozen small lines, probably sharpening grooves, seem to support the hypothesis of the use of iron chisels. About 6 m lower, five triangular forms are arranged around a small motif we interpret as a hoe, which would make it the only known depiction of a non-hunting implement at this site.

Zone C. On a 250 m-high summit, there are 23 well-made concentric circles (85%) and a unique seven-petal rose motif, together with a figure evoking interpretation as an insect with a giant head. About 10m to the east, three figures. stand out among others of a group. Two are of lizard form, the third is reminiscent of a tortoise carapace.

Zone D. Located on a large pavement on the north-east slope of the spur occur 42 pecked motifs, almost all of which are circles.

Zone E. A group of seven figures, including two animal motifs.

The Kongo Boumba Sites

Kongo Boumba 2 site. On a flat paragneiss dome, this newly-found group of rock art petroglyphs comprising about 30 figures among which concentric circles predominate. We also discovered the first cruciform representation here, next to two lizard forms.

Kongo Boumba 3 site. Three small rocks reveal some petroglyphs: roughly pecked circles, concentric circles, a lizard-like shape and probably a double-bladed throwing knife.

Kongo Boumba 4 site. Overlooking a forest is a group of boulders bearing more than 30 pecked circle rock art etroglyphs, together with seven lizard-like figures.

Kongo Boumba 5 site. Looking down upon a path, two enormous rocks present flat surfaces with rock art petroglyphs. On Rock A, two zoomorphs are found, one above a net-like maze, while Rock B bears two lizard-like figures and round pecked areas.

The Lindili Site

Located 8 km south of the cultural area of Kongo Boumba, a rocky hillock rises above a marsh. More than 20 figures are engraved on its rock surfaces. They comprise, on the one hand, circles including a chain of 11 concentric circles, and on the other hand, pecked zones and meandering lines.

The Kaya Kaya Site

Discussion of Gabon Rock Art Sites

At the present time, the Ogooue valley contains the major part of the sites, with the discovery of more than 1000 recorded petroglyphs, essentially on paragneiss rocks. This open air rock art seems closely related to its geological environment, being distributed in savannah enclave landscapes which occasionally abound with rock outcrops.

These approaches are limited, however, since oral tradition as well as history are silent about the petroglyphs, which are ignored by the contemporary local population. Thus it is difficult to determine the antiquity of the art. By considering the patina on the figures and the fact that they were certainly made with iron chisels (Oslisly 1989), and according to the chronology of the Iron Age which is well known in the middle Ogooue valley, we would expect the age of the petroglyphs to lie somewhere between 2500 and 1800 years BP.

The archaeological site closest to the Elarmekora Hill rock art petroglyphs is about 200 m from them. It consists of an occupation deposit of the Iron Age (Gif 8051: 1850 ± 60BP), with slags and ceramic fragments bearing decorations made of concentric circles like those found on the nearby rock outcrop. In addition, an accumulating body of radiocarbon dates (2300 - 1800 BP) around the beginning of the Christian Era indicates a flourishing Iron Age occupation of this region (Oslisly and Peyrot 1988, 1992).

The age of the site of Kaya Kaya is more difficult to assess because the rock art petroglyphs visible on the very hard sandstone blocks show evidence of erosion; they are blunt and polished by the waters of the small Missitigui river. They were made with the help of metal tools and they may date to about the beginning of the Christian Era, because the entire region at the confluence of the Mpassa, Ogooue and Lebombi rivers has a very rich archaeological context with an Iron Age presence since the fifth century B.C. With 1700 known rock art petroglyphs, the 0gooue valley axis has emerged as a very important region of open air rock art in western central Africa.

The Rock Engravings of Bidzar

The rock engravings of Bidzar were discovered by the french researcher Buisson in 1933. Other researchers were Jauze (1944), J.P. Nicholas (1951), E. Mveng (1965). In 1970 A. Marliac rediscovered the site and carried out some further studies, A. Marliac (1982). Bidzar is a small village near Guidar, situated on the Maroua-Garoua road in the north of Cameroon. The field of marble extends in the west of the road for about 2.5km long and 1km wide. The total length of these engravings have long been considered by some researchers as natural. A great quantity of marble was destroyed because of the industrial exploitation.

The Material

The material on which the engravings were carved is the calcareous marble (cipolin) from which the presence of schist (rock), rich in chlorites, modified its whitish colour producing hues of green, yellow, blue or pink. This marble seems to have been chosen voluntarily because its resistance to engraving is very low, whereas the neighbouring rocks such as granite are too hard and the micaschist too soft. The engravings could only have been done with iron tools; the first layer of the marble is easily removed giving way to the whitish and most resistant part of the rock.

Techniques of the Engraving

The engravers knew the usable material beside the neighbouring and less favourable rocks. In most of the cases, the engravers of Bidzar used a direct thrown percussion i.e. The hammering of a hammer placed on the engraved surface. The mark by staking is observable on the engravings; the engravers seem to have chosen the surfaces having no cracks or holes.

The disposition of the engravings on the paving stones seems to be linked either to the spread of the available surfaces (at times the surfaces are empty, at times full) or to the choice of the engraver. The engraver probably began the design at the greatest circular part, especially in the case of complicated figures. Then later added the internal figures and the external parts. It also worth noting the presence of huge figures occupying the whole paving stone, although nothing appears in these figures, the possibility of internal designs remained. engravings could only have been done with iron tools; the first layer of the marble is easily removed giving way to the whitish and most resistant part of the rock.

Two types of degradations can lead to the wearing away of the engravings: Natural destruction caused by erosion (water flow) and the degradation of the marble (cracks) by climatic agents. Human degradation, The field of marble at Bidzar has been long visited by men and animals, which has led to an increase in the deterioration of the marble. One can also note the piling up of stones and freshly made holes during cultivation periods.

To resolve these problems an enclosure was constructed around the most important fields of marble. The policy of preservation needed to be put in place, as the paints and coatings that may have been used on the engraving were being erased over time due to climate and erosion.

Dating of Bidzar Rock Engravings

It is difficult to give an exact date to these engravings, but studies have shown that they could not go beyond the early Iron Age (2500-1500 BP).

Interpretation of the Engravings

The Bidzar engravings clearly have a meaning, but their interpretation is subjective. Moreover the local population have no concept of their meaning.

In the north, paintings of the three rock shelters containing paintings are all situated at the Quadda sandstone area. The colours of the paintings are either white, black or red ochre. The anthropomorhic motifs (between 17 and 38cm high) are characterised by the pot handle-arch arms. In the Toulou and Djebel shelters, there are positive painted hands, as in Koumbala. In the Toulou shelter there is the striking presence of a large freeze depicting black, red and white figures.. The animal like figures are rare and represented by elephants and buffaloes at Toulou, by feline and lizard-form at Djebel Mela. The geometric symbols show points, lines, simple circles, triangles and herring bone patterns. The war like figures are represented by throwing knives.

In the south, there are more than 30 counted sites in the Bambari Rafai Bangassou region. It is essentially the engravings on the lateritic paving stones that are in the open air. This art is different from that in the north and west. At Lengo the animal figures depict antilopes, birds and felines. The remaining artistic expression is made up of war like figures represented by throwing knives, spears, axes, bows, arrows. The geometric forms are equally circularand rectalinear.

The west is represented by the unique site of Bwale situated in the Carnot sandstone developments. Over a hundred paintings reveal some geometric figures and anthropomorphic figures with guns.

In the north, we have many paintings while those of the south are almost esentially engravings on the lateritic paving stones. From a chronological point of view the south and west engravings may be of Iron Age. In the north however, dating is much more difficult as the objective elements are lacking.

Man visited these caves and rock shelters for long periods - the excavation of the Ntadi-Yomba rock shelter revealed occupations of hunter-gatherers dated to 7000 BP. The rock paintings are rare and were done either with ochre or charcoal. From the hundreds of caves surveyed, only five had cave paintings. The most significant forms are lizards and geometric motifs of which some present square parrallelograms.

The two shown below, from the Congo, have been photographed by R. Lanfranchi (1994).

Implications for the Environment by Richard Oslisly

Taken from 'African Rain Forest Ecology and Conservation' An Interdisciplinary Perspective, Edited by William Weber, Lee J. T. White, Amy Vedder and Lisa Naughton-Treves. Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2001

Africa is extremely rich in prehistoric archaeological remains. These include the extraordinary geological deposits of eastern Africa, where many important human fossils have been discovered, as well as the extensive areas of rock art in the Sahara and in southern Africa. However, there is a strong bias in the literature toward regions with open countryside, which are more easily explored. Little information exists for the tropical forested regions of central Africa, long considered a hostile environment that had resisted human settlement.

Early archaeological research in central Africa was sporadic. The forest vegetation soon covers any remains of settlements, and early discoveries were mostly by informed geologists working on large engineering projects. More systematic archaeological research began in the 1960's, particularly in the context of the “Bantu phenomenon” of the past five thousand years, when agriculturalists from just south of the Sahara expanded into eastern and southern Africa. As this research developed, it became apparent that late Quaternary climate changes of the Wurm glaciation (70,000-12,000 B.P. - the recent Pleistocene period) and the following interglacial of the Holocene (12,000 B.P. to the present) had played an important role in determining where and how people lived (Mortelmans and Monteyne 1962; DC Ploey 1963).

This text presents the results of sixteen years of work on the paleoenvironment and prehistory of the middle valley of the Ogooue, and builds the first chronological framework of the history of people living in this region of central Gabon and discusses their cultural traditions and relations with the forest. Findings from central Gabon will then be compared to research elsewhere to discuss the implications of human settlement and use on the African forest zone in general.

From a map of central Africa it is apparent that areas of southern Cameroon-bordered by the Atlantic to the west and the great swamps of the Congo Basin to the east-represent a likely channel for human population movements south out of the Bantu homeland in southeastern Nigeria and western Cameroon. This is especially so because during periods in the past, much of the present forest cover of the region was replaced by a more open landscape.

The natural funnel of ridge lines running north-south from the north of Gabon is interrupted in the center of the country by the middle valley of the river Ogooue, which runs parallel to the equator in a series of rapids and falls. The region is delimited to the north by the equator and to the south by the first forested foothills of the Massif du Chaillu. It is an island of open savannas and gallery forests covering about 1,000 km.sq.

As it is thought that the rapid spread of Bantu peoples may have occurred during a dry climatic phase between 3,500 and 2,000 B.P when savanna vegetation was more extensive in central Africa (Maley 1992; Schwartz 1992), it seems likely that the middle valley of the Ogooue would have been a key staging area, because of its central location and the presence of a large river. The history presented here has taken many years to tease apart, and we continue to make new and exciting discoveries on a yearly, if not monthly basis. For prehistoric humans, the evergreen forest represented a challenging environment, the height and density of the canopy making orientation difficult. It was, however, an important source of food, and people probably traveled significant distances to gather fruits and nuts or to hunt and trap animals, as their closest relatives, gorillas and chimpanzees, do today (Tutin et al. 1991; Tutin and Oslisly 1995). It is extremely difficult to follow riverbanks because the vegetation is dense, but there are generally numerous elephant trails along the ridges between rivers, which even today are often adopted by humans. Following such trails, one catches occasional glimpses, through gaps in the trees, of distant peaks or valleys, which improve one’s perception of topography and distance. Elephant trails were thus likely key elements for early human migrations through the forest zone, particularly considering the general north-south orientation of the major ridge lines in Gabon. Today’s roads, be they national high-ways or foresters’ trails also tend to follow ridge lines, often revealing numerous remains of past human habitation. These ridge lines tend also to be rich in iron-bearing geological formations and could also have attracted Iron Age peoples for this reason.

The Early Stone Age

(400,000-120,000 B.P.)

There are numerous Stone Age sites in the middle valley of the Ogooue, including the oldest known stone tools in central Africa, discovered in the upper terrace of the Ogooue at Elarmekora (Oslisly and Peyrot 1992a) and estimated to date to around 400,000 B.P., in correlation with the mid-Bruhnes climatic change (Jansen et al. 1986). Unfortunately, as is the case elsewhere in central Africa, most sites are in river terraces or other stone lines, and therefore their stratigraphy is typically highly disturbed. Because of the strongly acidic soils (with pH generally 4-5) there are no bones or other organic remains to enable radio-chronological dating. Only for sites dating from the past 5,000 years are detailed radio-chronological, archaeological, and paleoecological data available.

The Middle Stone Age

(120,000-12,000 B.P.)

During the long dry period, the Maluekian (see below), which lasted from 70,000 to 40,000 B.P., many of the central African forests gave way to savannas (Roche 1979). During this period, brutal but infrequent rainstorms caused severe erosion, which deposited large quantities of stones, pebbles, and gravel in riverbeds. Peoples of the middle Stone Age lived close to these rivers, using the stones to fashion rough tools, including the choppers, picks, and scrapers of the Sangoan industry, which are common in riverbanks and around ancient lakes in central Africa. These industries tend to occur in flood-plain deposits, which are by nature very disturbed and remain poorly understood.

The following period, the Ndjilian, from 40,000 to 30,000 B.P., was humid and favorable for forest growth (Caratini and Giresse 1979) but very few human remains are known from this period.

From 30,000 to 12,000 B.P., equatorial Africa suffered a severe drought, the Leopoldvillian climatic phase, when forests were restricted to river galleries and moist mountain ranges (Maley 1991). Sea level was more than 120 m below its current position, revealing vast beaches, which were molded by the wind into dunes along the coasts of Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Congo. Sporadic rains again caused severe erosion, washing away clay and sand layers and revealing the base rock. Rising rivers carried stones and pebbles, which accumulated in the middle terraces, about 10 m higher than they are today. Hunter-gatherer peoples of this Lupembian period lived on hilltops close to water and made more sophisticated stone tools. Their throwing weapons, made out of stone collected from numerous rock deposits, suggest that they were living in an open savanna environment in which visibility was good. One finds these industries at the top of alluvial deposits, but to date there is no site in central Africa of known stratigraphy to provide a chronological reference for the Maluekian, Ndjilian,or Leopoldvillian period (Lanfranchi 1990).

| Chronological references (Years) |

Industry | Palaeclimate periods |

Major events |

| Present | Late Iron Age (800 BP to present) | Kibangian B (3,500 BP to present) | Leopoldvillian (30,000-12,000 BP) |

| 500 | |||

| 1,000 | Hiatus (1,400-800 BP) | ||

| 1,500 | Early Iron Age (2,500-1,500 BP) | ||

| 2,000 | |||

| 2,500 | Dry Phase (3,000-2,000 BP) Savanna Expansion Anthropic Influence | ||

| 3,500 | Neolithic Stage (4,500-2,500 BP) | Humid Phase Forest Expansion | |

| 4,500 | Kibangian A (12,000-3,500 BP) | ||

| 10,000 | Tshitolian Complex (12,000-4,500 BP) Late Stone Age | ||

| 30,000 | Lupembian Complex Middle Stone Age | Leopoldvillian (30,000-12,000 BP) | Dry Phase Savanna Expansion |

| 40,000 | ? | Ndjilian (40,000-30,000 BP) | Forest Expansion Humid Phase |

| 70,000 | Sangoan Complex Stone-line Industry | Maluekian (70,000-40,000 BP) | Dry Phase Savanna Expansion |

| 120,000 | ? | Pre-Maluekian (Eemien Stage) | Humid Phase |

Holocene Cultures

The Late Stone Age (12,000-4,500 B.P.)

Around 12,000B.P., in the Kibangian period, the earth became warmer and the climate moister, and once again forest colonized the savanna, sea level rose, and large areas of mangroves developed. Humans of this period made small tools, or microliths, from stone and demonstrated their improved technology with the advent of the bow and arrow. Remains from the late Stone Age are much more abundant than those of the middle Stone Age and include the well-known Tshitolian industry. These comprise many sites along the valley of the Ogooue (Oslisly et al 1994), as well as on either side of the lower course of the Congo River on the Teke Plateau and the Kinshasa plain in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Cahen and Mortelmans 1973), in the Niari Valley, Congo (Bayle des Hermens and Lanfranchi 1978) and the north of Angola (Ervedosa 1980). These hunter-gatherers lived mostly on hilltops in savanna areas but also inhabited caves and rock shelters.

Remains from the late Stone Age are occasionally found within the sandy-clayey layer above the stone line, which tends to be 1-2 m deep in the middle Ogooue region when it is present at all (in many places this layer has been eroded away). Within this layer, stone industries have been dated to between 9,000 and 6,000 B.P., placing this soil formation in the Kibangian. All late Stone Age sites in the middle valley of the Ogooue are located on hilltops, principally in savanna but sometimes on the forest crest lines, with the Leledi 10 site dated at 5,700 B.P. (Oslisly and White). They often appear as large eroded patches in the savanna, visible on aerial photographs, and in many areas erosion has washed away all remains. It seems that this erosion process, which is ongoing, began during a climate change in the Kibangian B (3,500-2,000 B.P.; Maley 1992).

These late Stone Age industries evolved from the Lupembian industry, which was characterized by small hand axes, picks, large arrowheads, core axes, and scrapers, but which also developed smaller, lighter tools called microliths. Their improved technology, which belongs to the Tshitolian complex, would have allowed the hunter-gatherers of the time to become more mobile than their ancestors. During the late Stone Age, large areas of stone fragments accumulated where tools were fashioned, and these are often visible today as patches of erosion. Neolithic and Iron Age peoples dug refuse pits, and Iron Age peoples also built furnaces to extract iron from ore. What landscape did these peoples live in? This question is difficult to answer, but a site that we have named Lope 2 (Oslisly 1993a) gives some useful pointers. This site has unusually well preserved stratigraphy, with three layers of charcoal, the first two of which are associated with numerous flakes and stone tools made from milky quartz and jasper (Oslisly et al. 1996):

• Layer 1, between 30 and 40 cm, is dated to 6,760 B.P.

• Layer 2, between 60 and 70 cm, is dated to 9,170 B.P.

• Layer 3, between 100 and 110 cm, is dated to 10,320 B.P.

Charcoal in these layers has been identified as belonging to Diogoa zenkeri and Strombosiopsis tetrandra (both Olacaceae), two species characteristic of mature rain forest in the region (Tutin et al. 1994). Analyses of levels of isotopic indicate that savanna vegetation dominated down to 50 cm depth (c. 8,000 B.P.), but samples from 60-120 cm (c. 9,000 B.P. and older) gave values that were intermediate between forest and savanna (see Schwartz et al. 1986 for an explanation of this method). Hence these hunter-gatherer peoples lived in an open landscape of forest-savanna mosaic and chose to live on a hilltop. They are likely to have fed on plants collected from within the forest, certainly hunted meat with bows and stone arrow-heads, and used the wood of forest trees for their fires.

Transition to the NeolithicFor the long Stone Age era, which ended around 5,000-4,500 B.P., there is nothing to suggest anything more than a gradual evolution of technologies among a sedentary population. In contrast, the variety of cultures that appeared in the Neolithic and Iron Ages probably reflects a series of waves of migration. The upper Holocene (5,000 B.P. to the present) saw a series of migrations of Bantu peoples from the grassy highlands of the Nigeria-Cameroon border into central Africa following two major routes (Phillipson 1985). The first, which appears to have been the most important, followed the area of forest-savanna contact to the north of the main forest block, leading first to the Great Lakes region of east Africa and then toward southern Africa. The second route was to the southeast, penetrating the equatorial forest in two very different directions. One wave, probably the older, followed the coast, making use of a band of small savannas that run down from Equatorial Guinea through Gabon to Pointe Noire in Congo. Analyses of archaeological remains suggest that the first Neolithic groups traveled this way around 5,000-4,500 B.P. The second wave followed the many major ridge lines running north-south into the interior (Oslisly 1995).

Neolithic GroupsIt is possible that the Neolithic traits of polishing stone tools and making pottery evolved in situ, but their sudden, widespread appearance in the region about 4,500 B.P. suggests that the first Neolithic peoples arrived at that time from elsewhere. The earliest known sites are in the Okanda area located on ridges in the Massossou mountains, notably Okanda 5, dated to 4,500 B.P. (A. Assoko, pers. comm.) and Okanda 1, dated to 3,560 BP. Excavations of refuse pits at Okanda 1 revealed a blackish substrate rich in charcoal and ashes from cooking fires, in which there were large pieces of pottery, a small pestle, the nucleus of a stone tool, and two flakes. The pottery remains are from spheroid receptacles characterized by uneven curvatures, some with annular bases and outward-bevelled, thicker top lips. The decorative, grooved patterns, made using a comb, distinguish this pottery style from that of later Neolithic cultures.

The pottery of this recent Neolithic stage is stereotyped, with extreme constancy of form and decorative motifs over a long time period. This provides the first direct evidence of migration, since pottery of the same style in different places can be dated. Three types of vase can be defined: (1) keel pots, of which one fragment possesses decorated handles on its side; (2) bilobed pots, some of which have holes in their sides to enable them to be suspended; and (3) simple pots with out-curving lips. Bilobed vases with suspension holes and pots with out-curving lips similar in style to the pattern of the Epona group have been found on the coast at Lalala (Farine 1963) and at Okala, close to Libreville (Clist 1988), dated to a more recent period between 2,400 and 2,100 B.P. This suggests that there was cultural movement to the west of the middle Ogooue valley (Oslisly and Peyrot 1992b).

This hypothesis is further supported by the presence in the Lalala and Okala sites of polished stone axes made of amphibolite, a raw material available only in the middle valley of the Ogooue. In fact, tools made from this material are found throughout Gabon, demonstrating the extent to which these Neolithic groups traveled from their epicenter in the middle Ogooue valley.

Once again, these Neolithic groups inhabited hilltop sites, establishing a central platform around which one or two rubbish pits were dug. The settlements were invariably small, indicating low population density. Although rubbish pits were small in number, they have proved to be rich in information and archaeological remains. For example, one remarkable pit at the Otoumbi 13 site contained 13 kg of pottery, three grooved stones, one small pestle, two pitted stones (used to crack nuts), eleven polished stone axes, and numerous chisels and polished stone flakes. Refuse pits typically contain large quantities of charcoal from household fires, as well as fragments of the nuts of Elaeis guineensis (oil palm), Coula edulis, and Antrocaryon klaineanum. These small groups of people probably lived off forest resources, and to date there is no evidence of their practicing agriculture. Bone fragments in a pit at Otoumbi 13 (Oslisly 1993a) demonstrate that they hunted bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus) as well as some smaller mammals, but such remains are rarely preserved because of the acidic soils of the region.

The Early Iron Age

Ironworkers of the Okanda Tradition

Ironworking in west central Africa began in the Mandara mountains in northern Cameroon (MacEachern 1996) and in the area around Yaounde in the south (Essomba 1989) around 2,600 B.P. The first evidence from the middle valley of the Ogooue is around 2,600-2,500 B.P. at Otoumbi 2 and Lope 5, but it was not until around 2,300-2,100 B.P. that the Okanda tradition expanded, to the Otoumbi 4, Okanda 2 and 5, and Lindili 1 sites. The arrival of the new Okanda pottery style coincides with the abrupt disappearance of the Neolithic peoples. From a strictly chronological viewpoint, radiocarbon dates suggest that the first ironworkers may have coexisted with the last Neolithic peoples, but the range of dates for each group suggests that if they did cohabit, it was not for long (Oslisly and Fontugne 1993). There is no evidence of coexistence from cultural remains, suggesting that the superior weapons of the ironworkers enabled them to supplant the previous inhabitants.

These ironworking peoples invariably lived on hilltops, but their villages were much larger than those of the Neolithic culture; the flat hillcrest was surrounded by belts of refuse pits, with furnaces nearby on the first slopes. These furnaces were built from clay to an average height of about 1 m above the ground and were ventilated through pipes entering the base at ground level. The ironworkers seem to have been more numerous than the Neolithic peoples; almost twenty known sites date between 2,300 B.P. and 1,800 B.P.

Pottery styles can be used to map the expansion of the Okanda group. Their pottery was particularly distinctive and completely different from that of the Neolithic Epona group. The closed and bilobed shapes disappeared, to be replaced by larger, taller, bell-shaped pots with handles (including one that was 50 cm high, with a capacity of 30 liters), decorated with characteristic patterns. The most typical feature of the pattern is the presence of concentric circles on or at the base of the handles.

Similar concentric circles appear among the iconography of rock engravings at the Doda, Ibombi, Kongo Boumba, and Lindili sites (Kongo Boumba area) and at the Epona and Elarmekora sites (Epona area). These engravings were made by hammering pointed iron tools to form cuplike depressions in the rock. They cannot be dated directly, but the patterns correspond to those found on Okanda pottery dated between 2,300 and 1,700 B.P. (Oslisly and Peyrot 1993; Oslisly 1996). Of just over 1,600 engravings found to date, 67% are simple or concentric circles similar to those found on the handles of pottery (Oslisly 1993a, 1993b). In all, geometric shapes account for 75% of engravings, emphasizing the importance of abstract, symbolic characters. More realistic and vivid are animal representations, which account for a further 8%, portraying small quadrupeds or reptiles; but there are no depictions of such large mammals as elephants, buffalo, or antelopes, as are found in engravings in the Sahara and southern Africa.

A third, poorly represented group includes such weapons and tools as throwing knives (the classic weapon of central Africa), spears, axes, and hunting nets.

Looking at the types of images portrayed, one can identify two styles, one abstract and symbolic, the other figurative. The dominance of symbolic figures suggests that the engravings served a magic or mystic purpose, illustrating events in an abstract form. Circular forms perhaps depict a culture inhabiting small open savannas enclosed by the forest.

Ironworkers of the Otoumbi TraditionA new wave of ironworkers arrived in the middle Ogooue valley around 1,900 - 1,800 B.P. and took up residence on the hilltops vacated by the Okanda peoples. Apparently, after inhabiting the area for four or five centuries, they moved away to the south, following ridges through the forest to the savannas that descend toward the center of the Massif du Chaillu to the west of the Offoue river, and then on to the savannas of the upper Ogooue and northwest Congo. Such a scenario corresponds well with the more recent radiocarbon dates of iron smelting at Moanda in the upper Ogooue valley around 2,300 -1,800 B.P. (Digombe et al 1988) and on the Bateke plateau around 1,600-1,500 B.P. (Pincon et al. 1995).

The Otoumbi ironworkers used the same smelting methods as the Okanda, but their pottery styles were new, with medium-sized pots that had out-curving lips and flat bases, decorated with indented lines, as well as small bowls with incurving lips. They were without handles and the decoration was more complex. A new style applied with a notched wheel appeared, and concentric circles were no longer featured. Similar pottery has been found 200 km further north in Gabon, at the Oyem 2 site in refuse pits dated to 2,300-2,200 B.P. (Clist 1989), and although data are few, the indications are that the Otoumbi ironworkers arrived in the savannas of the middle Ogooue valley from the forests to the north.

These peoples expanded out from the Otoumbi area (see figure 7.5) between 1,900 and 1,600 B.P. along either side of the river and along ridgelines into the forest to the south, leaving tell-tale furnaces (at Anzem 1 and Mingoue 5) as well as large areas of charcoal from forest fires, dated to 1,500 - 1,400 B.P. (Oslisly and Dechainps 1994). These charcoal deposits represent the first evidence in the region of people with an itinerant slash-and-burn lifestyle living within the forest.

The HiatusWhereas the presence of ironworkers in the region has been confirmed for the period 2,500 - 1,500 B.P., radiocarbon dates suggest that between 1,400 and 800 B.P. the middle Ogooue valley was devoid of humans. No remains from this period have been found among seventy five sites dated so far (Oslisly 1993a, 1995). This suggests that a brutal phenomenon affected Iron Age peoples such that the region was empty until the arrival of the peoples of the recent Iron Age, who were the ancestors of populations present in the area today. The effect is not due to an ananomaly in the calibration curve of 14C values with time, because it is essentially linear during the period in question (Stuiver and Becker 1993), and indeed the phenomenon is not restricted to the middle Ogooue valley; human remains dated during this period are rare throughout Gabon. The carbon dates that do fall between 1,400 and 800 B.P. are spread across the three coastal provinces, Nyanga, and the Haut Ogooue, but there is no evidence of human populations during the same period in the four other provinces of Gabon, which account for 46% of all carbon dates available for the time period (90 of a total of 194).

Was this hiatus caused by a severe epidemic? The tropics are certainly recognized as a region of crippling endemic diseases where sudden outbreaks can devastate human populations. For instance, early in the twentieth century bubonic plague devastated populations in many parts of Gabon (Deschamps 1962). At the start of my work, I was surprised to find sites that seemed almost intact, with artifacts lying on the surface of the ground as if suddenly abandoned. In an area where conditions were already difficult and settlements small, a serious illness could have decimated Iron Age communities in a very short time. This seems to be the most likely explanation for the population void and may even be the reason for the current low human population density. It would not be surprising if such an epidemic led to a taboo, preventing repopulation of the area by surrounding peoples.

The six-hundred-year “human silence” most likely led to significant changes in the forest-savanna mosaic of the middle Ogooue valley. Anthropogenic fires, which currently maintain the savanna, would have been much less frequent, and the forest would have expanded dramatically, given that humid conditions favorable for forest growth have been prevalent in the region since 2,000 B.P.

The Late Iron Age

Ironworkers of the Lope and Leledi Traditions

Ironworking populations reappeared in the middle Ogooue valley from 800 B.P. and again occupied hilltop dwelling sites. Ceramics of this period include large and small pots of flattened spherical shape with out-curved apexes and pots of uneven curvature, as well as clay pipes. The decoration of these pots is unique, with small circular motifs made with knotted strips of plant material arranged in herring-bone patterns. The designs on pots form a band of variable width high on the sphere, and similar patterns are found on the clay bowls of pipes. This distinctive pattern has also been found on a pot from a cave at Lastoursville, 150 km upstream (Oslisly 1993a, 1995). Seeds of Sesamum cf. calycinium (Pedaliaceae - a species of sesame), which, when pounded, yield edibl oil, were found on the inside of this pot. Carbon dates from sites containing this style of pottery confirm historical and linguistic studies of the Okande peoples currently resident in the area (Ambouroue-Avaro 1981), which suggest that their ancestors arrived in the region around the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

This same style of pottery, named Lope, has been found in an area greater than 1,500 km.sq. in size and indicates that a unified cultural group occupied at least 250 km along the length of the Ogooue valley. This would have been possible because of these people’s renowned skill at navigating the rapids of the Ogooue by dugout canoe, described by Savorgnan de Brazza in 1876 (Brunschwig 1966).

New and ongoing research has revealed numerous furnaces and extensive remains of slag along ridgelines opened up by logging roads in the middle valley of the Leledi to the south of the Ogooue in a forested area at about 500 m altitude. Carbon dates fall between 800 and 200 B.P. Associated pottery found to date has been badly weathered, but the form, pattern, and composition are completely different from those of the Lope tradition. Iron-smelting furnaces of these peoples consisted of holes dug to about a meter down into the sandy-clayey layer, into which alternate layers of iron ore and charcoal were loaded, with large clay pipes angled downward, through which air was pumped by means of a bellows into the base. Previous smelting technology used in the middle Ogooue valley had involved the erection of a clay structure above ground, which had to be broken open and destroyed to obtain the iron. This new method would have facilitated removal of metal and waste and subsequent reloading and reuse (Collomb 1977), distinguishing between these recent Iron Age peoples and those of the early period.

Hence, from the fourteenth through the nineteenth centuries, ironworkers in the region lived both in savanna (Lope peoples) and within the forest (Leledi tradition), extracting iron using the same technology but making pottery with different form and decoration. We will have to undertake further research to ascertain whether there was any commercial or cultural exchange between these two groups.

It is a sad reflection on “progress” that pottery traditions which had lasted about 4,500 years rapidly became extinct with the massive recent importation of containers from Europe. Pottery is no longer made or used in the middle valley of the Ogooue.

Climatic Savannas Isolated within the ForestFollowing the long dry climatic phase of the Leopoldvillian, when savannas dominated the central African landscape, forests recovered in the humid Kibangian, reaching their present distribution around 6,000 B.P.(Maley 1987). Aubreville (1967) has already proposed that the “strange” middle Ogooue savannas (he termed them Booue) are a paleoclimatic relict. They have now been dated to around 9,000-8,000 B.P. using and analyses (Oslisly and White, in press; Oslisly et al. 1996), suggesting that they are a relict of the dry Leopoldvillian climatic phase, during which they would have been much more widespread. Further evidence that these are ancient savannas comes from the local presence of specialist savanna animals and plants: for example, such bird species such as the long-legged pipit, Anthus pallidiventris; the pectoral-patch cisticola, Cisticola brunnescens; and the black-faced canary, Serinus capistratus, which are thought unlikely to cross large expanses of forest (Christy and Clarke 1994; P. Christy, pers. comm.). Savanna frogs of the genus Ptychadena, considered good biological indicators of ancient grassland, are also present (Blanc 1998; C. Blank, pers. comm.), as is the bushbuck, Tragelaphus scriptus, a mammal that lives in savanna and woodland vegetation but which does not occur deep in the forest. The presence of these savanna specialists is good evidence that a savanna corridor once connected the middle Ogooue valley to Congo.

Identification of plant species from charcoal found in village sites known to have been located in the savanna demonstrates the presence of indicators of mature forest vegetation within the forest-savanna mosaic during the late Stone Age (White 1992, 1995). Further more, charcoal from the forest tree Pterocarpus soyauxii (Padouk) was favored by all Iron Age peoples for smelting ore and must have been obtained from within the forests of the period. This paints a picture of successive groups of peoples living in open savanna but making extensive use of nearby forests. It would have been their fires, lit to maintain their open habitat and, perhaps more important, to facilitate hunting of large savanna grazers, that prevented recolonization of the savannas by forest vegetation. Equally, during the hiatus when fires would, presumably, have been far less frequent, savanna areas were colonized rapidly by forest species, illustrating the important ecological role played by humans (Oslisly andWhite, in press).

Research from the middle Ogooue valley does not provide evidence of true forest dwelling until the quite recent past. Even sites discovered within the forest today were actually located within savanna vegetation when inhabited (White and Oslisly, unpublished data). This emphasizes the need to take into account vegetation history when considering the dynamics of central African peoples, as well as when attempting to interpret the significance of archaeological remains.

Because of the lack of sites in forested central Africa with well-maintained stratigraphy dating to early or middle Stone Ages, we are currently unable to say much about the way these earlier peoples lived. From about 10,000 B.P. onward we possess a relatively detailed picture of population dynamics in the middle Ogooue valley, which demonstrates the arrival of a long sequence of civilizations, particularly from the Neolithic (c. 4,500 B.P.) onward. It seems that the major migrations of Bantu ironworkers were linked to a dry climatic phase in the Kibangian B (3,500-2,000 B.P.), which probably resulted in decreased forest cover and may have enabled these savanna-dwelling peoples to avoid the prospect of a daunting trip into extensive forest vegetation (Maley 1992, Schwartz 1992;). These migrations were undertaken through Gabon following ridge lines (Oslisly 1995), although elsewhere river navigation was used (see, e.g., Eggert 1993). The migrating peoples seem to have favored areas with at least some savanna vegetation, reflecting their origins outside the forest ecosystem, and it is not surprising that the middle Ogooue valley was appealing to them. It seems that they systematically supplanted resident cultures, although it is possible that they also assimilated some local knowledge (see, e. g., Vansina 1990).

Elsewhere in forested Africa, as in the middle valley of the Ogooue, the recent Holocene was a time of successive waves of migrating Bantu peoples replacing resident populations. Hence, the overriding theme of human settlement in the middle Ogooue valley, as well as in other parts of Africa, is one of savanna dwelling peoples who made use of the forest environment but who preferred to avoid dwelling within it as true “forest peoples.” Therefore, this is not dissimilar to present patterns of migration within the forest zone, which tends to result in forest conversion. This study demonstrates the rich and dynamic prehistorical past of the middle valley of the Ogooue, particularly during the Holocene, a period for which there are numerous archaeological remains. lt also raises a number of questions, perhaps the most fundamental of which is: How important are these isolated savanna regions to the history of human populations in the middle valley of the Ogooue, and how has the long history of human habitation affected the savannas and the surrounding forest? Ongoing multidisciplinary research on archaeology, vegetation history, palynology, and plant ecology should provide answers and also reveal to what extent the history of human populations in the central African region as a whole mirrors that of the middle Ogooue valley.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ The Rock Art of Africa

→ Tassili n'Ajjer

→ The Dabous Giraffe Petroglyph, Niger

→ The Rock Art of Niger

→ The Rock Art of Namibia

→ The Rock Art of South Africa

→ Hunter-gatherer rock art sites in Africa

→ Gilf Kebir - Cave of Swimmers

→ Animals in Rock Art

→ Rock Art of Western Central Africa

→ Where is the Oldest Rock Art?

→ Africa's World Heritage Sites (Film)