Ice Age Europe, approximately 20,000-13,500 years ago; a period known as the Magdalenian. The climate is gradually ameliorating after glaciers and cold temperatures reached their height in the Last Glacial Maximum. Despite this, the landscape is frozen, arid and unforgiving for all who live within it. Dispersed and highly mobile hunter-gatherers populate this harsh environment. These Magdalenian people adapted to the landscape by using all available resources to create a rich and diverse material culture, which included tools, highly efficient hunting projectile weapons, tailored clothing, cave art, portable art, beads and much more. All aspects of this culture depended on relationships with other human groups, and an intimate knowledge of animals that were a crucial resource during this period, enabling the Magdalenian people to survive. It is these relationships, how they were maintained by these people, and how they shaped past identities and social behaviours, that are the key to better understanding our ancestors’ social lives and behaviours.

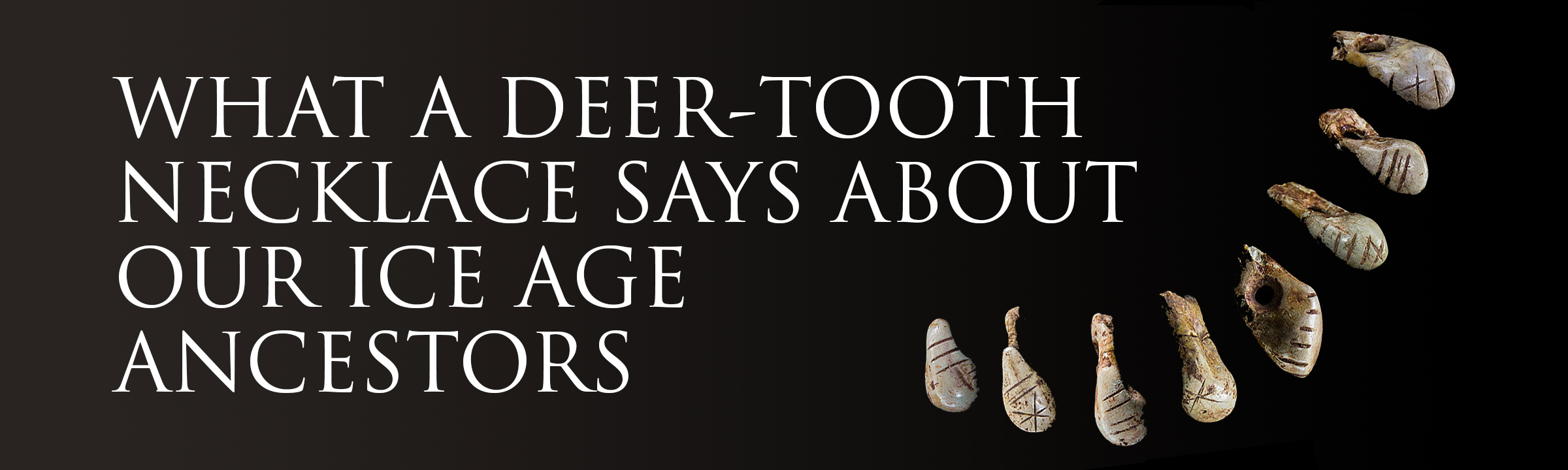

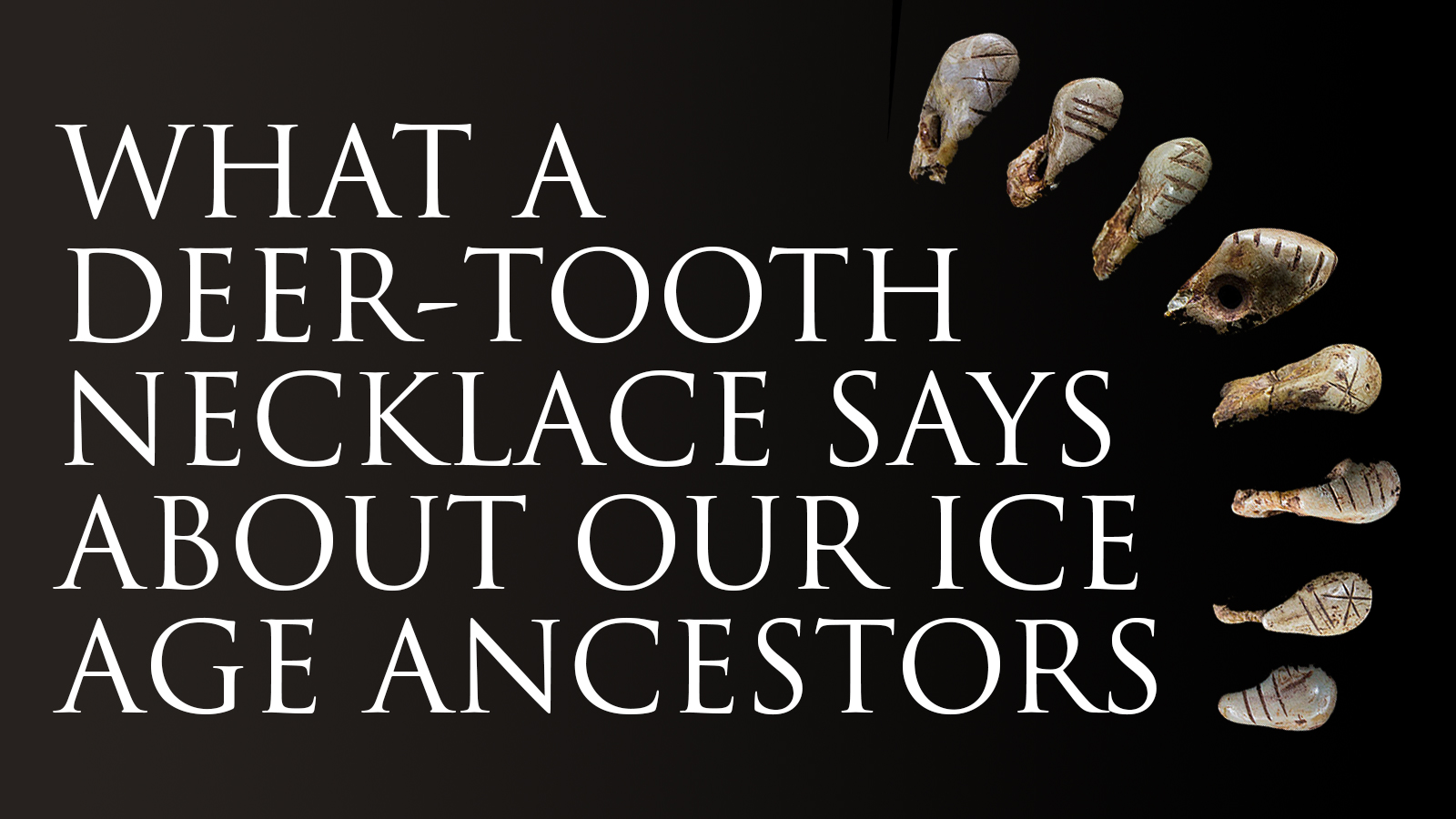

During this period, around 19,000 years ago in southwestern France at a site called Saint-Germain-La-Rivière, an adult woman dies and is prepared for burial by members of her society. She is adorned with 70 red-deer teeth that were perforated by a flint tool to be used as beads; many of which have a unique engraved design and were smeared with red ochre. These beads provide a window into the period, giving an insight into the way our Magdalenian ancestors negotiated relationships, and the importance of this meshwork of relations to their survival. The burial context of these beads demonstrates how these relations took centre stage in the social lives of Magdalenian people. Untangling the object biographies of these beads – the way they were made, used and deposited – can reveal the creative ways our ancestors used objects to negotiate and embody intricate human-animal-object-landscape relationships. Insight into the ‘lives’ of these beads can be achieved by contextualising the successive stages of their biographies within the environmental and social conditions of the Magdalenian.

The first stage of the beads’ biographies immediately reflects their significance within this society. The beads are made from red-deer teeth, from approximately 63 red deer. One might initially suspect that this represents the hunting prowess of people in this society, but if this initial stage is contextualised within the environmental and ecological conditions of the period, the narrative becomes much more complex. The frozen environment of southwestern France was unsuitable for red deer; in fact, this species makes up less than 1 per cent of the faunal record from the site of Saint-Germain-La-Rivière. The group that lived here were not hunting red deer, certainly not to the extent that they could acquire teeth from 63 animals, so where did the teeth come from?

The nearest region with an abundance of red deer during this period was around 300 km away in northern Spain. Palaeoenvironmental research from archaeological sites in this region demonstrates that this was not an entirely arid landscape during this period, and thus benefitted from dispersed areas of deciduous trees; ideal conditions for red deer, which were much more abundant in this area. This is likely where the beads originated from, and perhaps were acquired by exchanging objects and materials with different social groups from this region. Therefore, these beads, from a very early stage in their biography, tell us a story about the relationships between groups from different regions in Europe.

The narrative of these beads’ lives becomes further enriched as we understand their production. The beads are not all alike; each one is uniquely perforated and decorated. The reproduction of these beads through experimental archaeology suggests that about an hour is required to perforate each tooth, but the variation in the shape and size of the perforations represented by the Saint-Germain-La-Rivière beads couldn’t have been achieved accidentally. Each perforation might therefore reflect an artistic ‘flair’ or preference, with differences in the production of the beads potentially reflecting many unique authors.

The individual nature of each bead is further emphasised by their decoration. Incised lines were carved into the enamel with a sharp flint blade, and made visible by the application of ochre to bring out the design. It is safe to assume, then, that the beads were intentionally created to be distinct, and perhaps this was meant to reflect the multitude of individual people within the society. Each bead represents a person, a bead-maker, with the individual’s identity reflected in the features of each bead.

The beads were made from the deconstructed parts of red deer, and the unique work of many different humans, expressed through the distinctive perforations and decoration. These actions fuse together a conceptual aspect of the unique nature of each person to the literal parts of red deer; the beads become a hybrid deer-human object. One bead embodies relationships between different groups of humans through its acquisition, and a more intimate relationship between many different people and red deer. Stringing together these multiple deer-human hybrid beads as one necklace might have been intended to represent the social coming-together of different people and different red deer, all embodied by one object. This hypothesis is difficult to prove, but it is a suitable explanation for the particular nature of this necklace, with its individual, distinctive beads. The effort and cooperation involved in creating this object must have been far from trivial, and instead had great significance for the people who made it.

Yet, despite the interplay of human-animal relations, and the extensive effort exerted to create these beads, there is, surprisingly perhaps, no evidence that they were ever worn before being deposited. They were probably made exclusively for the burial. This stage of the object biography of these beads further elucidates their role within mortuary behaviours. It was perhaps pertinent that the beads, which through their making collectively represent the identities of many different people, were associated with the one adult woman in death. The association of these beads to this woman helps us reconstruct some of her identity: she is no longer buried alone, but with material representations of many different people in the society expressed in the parts of many different red deer.

We might never know precisely why such lengths were taken to select red deer for this role, nor why it was so significant for the society to make so many unique beads for her burial. However, through considering the object biographies of these beads, we can begin to appreciate something of how our ancestors related to the world around them, using objects as a way to mediate social relationships between each other, and between themselves and other animals within their world.