This is an account written by the eminent French prehistorian Dr. Jean Clottes, presented as part of the Bradshaw Foundation India Rock Art Archive. Jean Clottes is the first to admit that 'Indian rock art is not as well-known abroad as it should be', despite the fact that the country contains a vast concentration of ancient rock paintings. His research in this Archive, along with that of Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak, highlights both the sheer number of rock art sites as well as the quality and diversity of the prehistoric rock art found in the shelters. Because of this, its preservation - through awareness and appreciation - is clearly essential.

Despite the excellent work carried out by my Indian colleagues in the past quarter of a century, Indian rock art is not as well-known abroad as it should be. And yet it is both extremely abundant and spectacular. It has often been said in the recent local literature that India shares the privilege - with South Africa and Australia - of possessing one of the three largest concentrations of rock art and petroglyphs in the world. Be that as it may, it is certain that the sites with paintings and/or engravings are exceptionally numerous all over the country, particularly in its centre.

This is why, when an International Rock Art Congress was organized in Agra (Uttar Pradesh), south of Delhi, in November/December 2004, and I was invited to participate in it, I immediately agreed and registered on two of the after-Congress field trips to see some of the surrounding rock art. The Congress was the Tenth Congress of the International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO), the first of its kind to be held in India, and it was organized by Dr. Giriraj Kumar on behalf of the Rock Art Society of India (RASI).

I shot all the images shown here during the two field trips that, under the guidance of my Indian colleagues, took us first to the rock art sites of Karabad, in the Raisen district and to those of the Shamla Hills next to Bhopal, then to more than 20 of the numerous painted shelters of Bhimbetka, and finally to Magazine Shelter and Chaturbhujnath Nala in the verdant Chambal valley and its tributaries. All these sites are in Madhya Pradesh, the state with most rock art in India.

As to the general information provided hereafter most of it is taken from books and articles published in the past twenty years (see references at the end of this page). My aim is to pass on some of the information I gleaned through the writings of my colleagues and their painstaking work and also - through the images- some of the wonder I felt when I approached a whole new world of rock art.

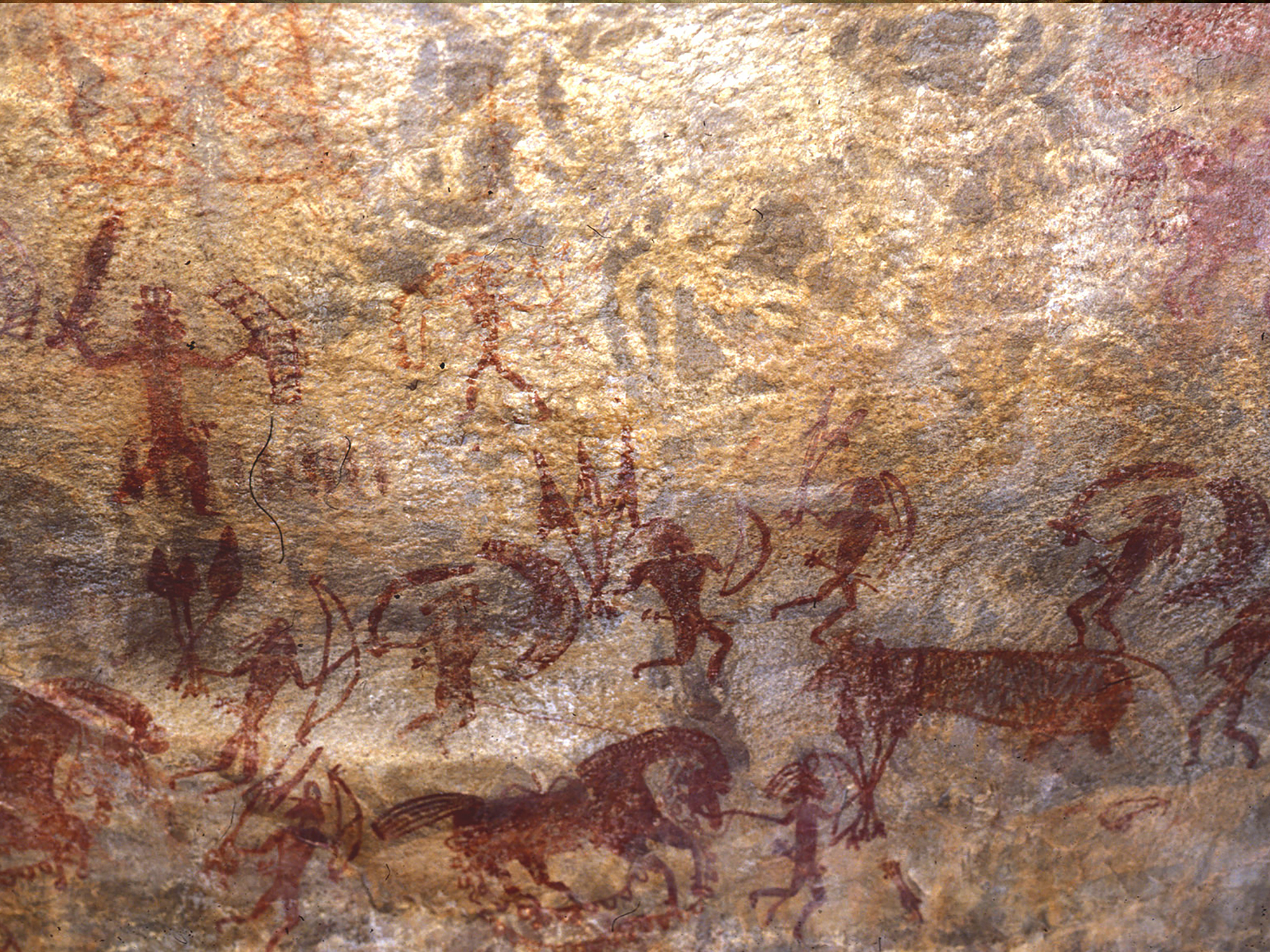

For the first series of sites, our base was Bhopal, the capital city of Madhya Pradesh. The Karabad sites, west of it, are a series of small shelters about 120 feet above a valley. As is most times the case, these sandstone shelters are rather shallow, so that the paintings have always been done in the daylight. They were an excellent introduction to Indian rock art with their herds of bovids with inner body decoration, sometimes all red or all white, more rarely red and white. Other animals, like a rhino (an animal that became extinct by the end of the Chalcolithic), elephants, deer and big cats were present, as well as a composite creature, i.e. a human with fantastically long limbs and an animal’s head and other humans. The absence of warriors and inscriptions and the high number of animals put those paintings in a rather early phase of the art, earlier than the Historic period to which so much Indian rock art belongs. Many superimpositions occur, as is the case in European Palaeolithic art even though the images here are much later. These superimpositions can sometimes become quite clear when images are enhanced.

Near Bhopal, we visited the superb Shamla Hill ethnographic park, which provides information on many Indian tribes, with reconstructions of their houses, ceramics and art. In particular the Sauras (or Saoras) in Orissa to the west of the subcontinent still pursue their traditional way of life and "prepare elaborate pictographs in white called ittals or idittal on both inside and outside walls (of their houses) and offer them animal sacrifices to please supernatural powers towards remedy diseases and magically inflicted troubles as well as to improve the fertility of crop".

In the park, a series of painted shelters, open to the west, face the lake. Many of the images are faded, but a beautiful series of stags stand out, as does the image of a man next to an animal that could be a rhinoceros.

The Bhimbetka rock art sites that we saw next, about 45 kilometres south-east of Bhopal, have become famous: they are the ones that are always mentioned whenever Indian rock art is alluded to. They were discovered and revealed to the world by V.S. Wakankar from 1957 onwards. Bhimbetka, set in the Vindhyan range of central India, is about ten kilometres by two. On seven hills more than 500 painted sandstone shelters are known in an environment of forests, nowadays threatened by population increase and pressure. Some of the painted sites are very minor, with a few images only whereas there will be hundreds in others. They were put on the World Heritage List of UNESCO in 2003. Fifteen or so of the most spectacular ones, in an environment of convoluted cliffs on the top of a hill with a large vista, are open to the public. They have been skilfully fitted up with unobtrusive but efficient passageways and protections, so that visitors can view the paintings at leisure but are kept sufficiently away not to cause any damage. Guards provide information whenever necessary and see to it that the regulations are not broken.

Excavations carried out at Bhimbetka have revealed occupational deposits ranging from the Acheulian to Historical times. As to the art, the three main periods recognized by most Indian researchers (Mesolithic roughly 12,000 to 5,000 BP, Chalcolithic (rougly 5,000 to 2,500 BP) and Historical, from 2,500 BP onwards) are present on the shelter walls. The first impressions one has of the art have been graphically described:

"If one visits a painted shelter, one is confronted with two types of drawings - one very clear, bright and fresh looking, while the others, underlying them are faded, fragmented and hardly visible. The fresh ones feature mainly bands of marching and fighting soldiers, cavaliers being chased and aimed at by masked hunters equipped with bows and arrows and barbed spears. In between these two types of figures sometimes we find a third category … These are of long-horned cattle, other domesticated animals and men engaged in activities which can be associated with a primary stage of civilization - the beginning of sedentary life" (Mathpal 1998: 10).

On the walls hundreds of images, very often superimposed upon one another, constitute a fantastic canvas that has been many times reused to paint white and red figures. Yashodar Mathpal, who has recently studied most on those sites, has established the following succession for the art (Mathpal 1998), in nine Phases summarily summed up hereafter:

| SUCCESSION FOR THE ART (Mathpal 1998) | |

| Prehistoric | |

| Depicting the Life and Environment of Hunter-Gatherers | |

| Phase 1 | Large size animals (buffaloes, elephants, wild bovids and big cats), outlined and partially infilled with geometric and maze patterns; no humans. |

| Phase 2 | Diminutive figures of animals and humans, full of life and naturalistic. Hunters mostly in groups. Deer are dominant. Colours are red, white and emerald green (the latter with humans in S-shaped bodies, dancing) (Photos 81, 82). |

| Phase 3 | Large size animals with vertical strips and humans. |

| Phase 4 | Schematic and simplified figures. |

| Phase 5 | Decorative. “Large-horned animals” drawn “in fine thin lines with body decoration in honey-comb, zigzag and concentric square pattern” (Mathpal 1998: 11). |

| Transitional | |

| Beginning of Agricultural Life | |

| Phase 6 | Quite different from the previous ones. Conventional and schematic. Body of animals in a rectangle with stiff legs. Humps on bovines, sometimes horns adorned at the tip. Chariots and carts with yoked oxen. |

| Historic | |

| Phase 7 | Riders on horses and elephants. Group dancers. Thick white and red. "Decline in artistic merit" (Mathpal 1998: 11). |

| Phase 8 | "Bands of marching and facing soldiers, their chiefs riding elephants and horses (…), equipped with long spears, swords, bows and arrows" (id.). Rectangular shields, a little curved. Horses elaborately decorated and caparisoned. "White infilling and red outlining" (id.) (Photos 27 to 33, 88, 89). |

| Phase 9 | "Geometric human figures, designs, known religious symbols and inscriptions" (id.). |

Out of the 817 human figures he recorded, Mathpal identified 779 as men (95.5%), the others being children (16) and women (only 21). The animals (428) are dominated by horses (185, i.e. 43.2%), followed by deer (39; 9%) and bovids (37; 9%)). The other animals are much rarer (dogs, tigers, buffaloes, panthers, monkeys, etc.) (Mathpal 1998: 13).

Our second India trip in December 2004 took us to the Chambal valley region, in the Bhanpura-Gandhi Sagar area, north of Bhopal, still in Madhya Pradesh but close to Rajasthan. The highlight undoubtedly was the two separate visits we made to the Chaturbhujnath Nala sites, but we also visited two other very different sites that were quite interesting.

One of them can only be accessed by boat, after passing a military checkpoint and with special permission. After a half an hour ride up the river, starting from the huge dam on the Gandhi Sagar lake, we reached a big shelter a few meters above water level, called 4. Magazine Shelter. The painted figures were not very numerous and some old graffiti marred the walls. One painting in faded red was conspicuous and it was the only one of its kind that we saw. It represented a big (1.45m high) vertical crocodile, perfectly rendered in dynamic style with the internal organs described, i.e. in what in Australia is called the X-ray style. Next to it were nine small humans in small groups, including some armed with axes. On our return to the dam we had the good surprise to catch sight of a huge and very alive crocodile basking in the sun.

The Chaturbhujnath Nala sites, near Gandhi Sagar, extend over several miles on both sides of the small but beautiful river which is a tributary to the Chambal. Even though largely unknown outside India, they are of world importance and particularly significant, for a number of reasons.

The rock art is situated in a very beautiful unspoiled scenery, in a succession of shallow rock shelters strewn along both sides of the river, a few meters above it . As always, the environment is a most important part of rock art. That environment is being monitored and preserved within the Gandhi Sagar Game Sanctuary, by the Forest officers and staff, which means that the best conditions exist for its continuing conservation. In fact there are hardly any examples of the vandalism (graffiti) which could have been expected in such an open place. The 302 square kilometres Park was created in 1974 and protects numerous wild animals such as panthers, bears (chingaras), wild boar, barking deer, hyenas, wolves, foxes, porcupine and, naturally, monkeys.

The very long lines of shelters and their accessibility have made it possible to make thousands of rock paintings over rather vast distances. Others will no doubt be discovered in the future. In the company of their discoverer, Ramesh K. Pancholi, we saw an uninterrupted series of painted shelters along one kilometre, which make Chaturbhujnath Nala one of the longest and most important rock art "galleries" in the world.

The paintings themselves extend over a very long period of time (nearly 10,000 years, since the Mesolithic) and exhibit marked stylistic and thematic differences: those sites thus provide an invaluable record of the cultural beliefs and practices of the local people and must be considered as a precious and outstanding archive. Many are superbly rendered and as "good" as any great work of art.

After we saw them, we were in for a double treat: we visited a beautiful XIth century Hindu temple which is still renowned and used as a revered place of worship. After we had had a meal on the esplanade, we left and the place was invaded by a crowd of monkeys coming out of the woods in their dozens.

Contrary to what one might think, rock art research began very early in India. The first discovery of rock art we know of was done in 1867 by Archibald Carlleyle, then First Assistant of the Archaeological Survey of India, in the sandstone hills of the Vindhyas Mirzapur District (what is now Uttar Pradesh). This was twelve years before the discovery of Altamira. His discoveries were not published at the time, but long after, in 1906. On the other hand, in 1870, H. Rivett-Carnac, a Colonel of the colonial British administration, found and reported cupules near Nagpur, then in the state of Maharashtra. Then he found some more in Kumaon (Himalaya). In 1883, John Cockburn reported the painting of a rhinoceros hunting scene in the Mizrapur District and shrewdly attributed it to prehistoric times and made ethnological comparisons, so that"Cockburn’s views and concept on the rock art of India (are) still valid for further ethno-archaeological investigations" (Chakarverty 2003: 9).

A number of other officials subsequently reported discoveries : C.-A. Silberrad, F. Fawcett, V.-A. Smith, then C.-W. Anderson, M. Ghosh etc. Several Indian scholars, mostly University professors, like P. Mitra and A.-N. Datta, were pioneers in the field (op. cit.). In the nineteen thirties, D.-H. Gordon worked on the chronology of the art and he attributed the bulk of it to historical times, i.e. to a period from the 5th to the Xth centuries AD. As a consequence, people lost interest in an art that was supposed to be quite recent and that paled in comparison with the architectural and other marvels of Indian historical art (Wakankar 1992: 319).

The "father" of India rock art studies was Vishnu Wakankar whose memory is universally revered. When he discovered the Bhimbetka shelters in 1957, he started working there, both on the art and on excavations, and he attributed some of the images to the Mesolithic and even to the late Palaeolithic, which undoubtedly spurred research on Indian rock art. Because of his untiring work he discovered and reported many different rock art sites.

Yashodar Mathpal sees three broad periods in the history of rock art research in India. The first one, from 1867 to 1931, would be that of enthusiasts and explorers. During the second one, from 1952 to 1972, "more attention was paid to faithful recording" while "during the third period which still prevails, the study of rock art has become a science and a subject of research" (Mathpal 1992: 213-14). About the scientific work done during the third period and for more information, see the References hereafter.

As soon as 1883, John Cockburn had mentioned the fact that "the aborigines of the Kymores were in a stone age as late as the 10th century AD" and thus had had a very long artistic tradition (reported by Chakraverty 2003: 11). Nowadays, India is one of the rare countries in the world with a continuing ethnological tradition which has manifested itself in a vivid tribal life, even though, as far as we know, rock art has not been made for a very long time and the memory of its purposes and meanings has long been gone.

Nowadays, tribal and folk groups apparently do not "associate themselves with such art in their areas (…), except to explain it as the work of evil spirits or epic heroes" (Chakravarty & Bednarik 1997: 31). A similar opinion has been expressed about the rock art in Orissa (east of India), where "the local people do not attach any special significance to these rock art sites. To them, the works of art in the shelters are the works of the heavenly bodies or that of the ghosts. They even often consider it a taboo to touch such works of art" (Pradhan 2001: 27). Near Bhimbetka, the local belief is that "witches paint on these rocks during the dark nights of Kanaiya Aat (Shri Krishna Jurmashthami) every year" (Mathpal 1998: 9).

Some widespread forms of tribal art, however, are quite reminiscent of certain themes and techniques found in the rock art. For example, "in India, (the) tradition of printing hands on the gates of houses, temples, sacred sites at ritualistic ceremonies, auspicious occasions like the birth of a child, marriage ceremony etc., is still continuin" (Kumar 1992: 63).

This obviously does not meant that the hand prints found on numerous sites, such as at Bhimbetka Auditorium Rock (Photo 23), should automatically be given a similar meaning, "because similar patterns may well be the results of different behavioural processes in the past and present” (Chakravarty & Bednarik 1997: 87), so that “to read contemporary ethnographic rituals into ancient art may not be quite appropriate in spite of some common trait" (id.). One cannot but agree wholeheartedly with the caution expressed.

Still, the "common traits" and the rituals which accompany them when they have been well documented can be quite fascinating and provide us, if not with outright explanations, at least with food for speculation and wonder, with graphic examples not of what was precisely done with the rock art but of what could in certain cases be done.

The best examples we know are due to the work of Sadashib Pradhan in the south of Orissa, who did notice that "certain ethnographic parallels with rock art are quite discernible in terms of colour composition, geometric frames, symbolism and overall delineation of the subject matter of depiction" (Pradhan 2004: 39). The basis of his study was the Lanjia Saura, one of the numerous Orissa tribes (Photos 9, 10, 64 to 67). They are mostly hunter-gatherers and practise a little farming with traditional ploughs (Photo 68). They "live in close interaction with supernatural entities. When the primitive mind fails to comprehend the cause of unnatural tragedies like illness, killer epidemics, earthquakes, lightning strokes, attacks by wild animals, etc. it attributes the cause to malevolent spirits and gods (…) which need to be propitiated and appeased by drawing icons" (id.). So "art, prompted by sources of beliefs and myths, forms a part and parcel of the Saura life in their struggle for existence" (Pradhan 2001: 62) and it has kept unchanged for as long as it has been documented.

In his excellent book on the rock art in Orissa, Pradhan devotes a whole chapter to the "ethnoarchaeology of rock art". He thus sums up the creation and use, in three broad stages, of the traditional paintings still being made: "In stage one, the shaman identifies the spirit or the power that has caused the disease, or death or that needs to be propitiated for the welfare of the family, whose icon is to be drawn. In stage two, the icon is drawn on the house wall either by the artist (Ittalamaran) or the shaman (kuranmaran) if he knows how to draw. And in stage three the icon is consecrated by the shaman through an elaborate ritual involving invocations to all gods and spirits of the Saura world and the particular spirit in whose honour the icon is prepared, to come and occupy the house. All sorts of fruits, roots, grains, corns including wine were offered and finally either a goat or a fowl is sacrificed." (Pradhan 2001: 59).

All the details Pradhan gives in his book show the richness of the information to be got from traditional tribal beliefs and practices. No doubt much remains to be learnt from those sources in many other parts of India.

Somewhat surprisingly for such a wide continent, Indian rock art has often been considered as pertaining to a "cultural unity", as is the case for Upper Palaeolithic cave art in Europe. Disparities do exist according to the areas, so that regional groups have been and will no doubt be defined (see for example Chandramouli 2002 for the rock art of Andhra Pradesh in the south of India, or Mathpal 1985 for that of Kumaon in the north). However, "in spite of the great distances of the different regions Indian rock paintings bear surprising affinity in forms, subject matters and design elements to their contemporaries" (Kumar 1992: 56).

The only petroglyphs (i.e. rock engravings) we have mentioned are cupules, because we hardly saw any other engraved motifs during our trip. Still, it is necessary to recall their existence and their importance in many parts of India, even if we are here focusing on pictographs (i.e. rock paintings). Among the colours used red is overwhelmingly dominant, at all periods. It comes from iron oxides such as haematite. White (from a white clay like kaolin) has also been widely used. Other colours are scarcer, like "green and yellow derived from copper minerals" or "blue or coal black obtained from manganese or charcoal" (Chakravarty & Bednarik 1997: 46). Painting was carried out "by rubbing the colour nodule dry, or with water, without any visible use of organic binding material, using finger tips, twigs, hair brush or by spraying with the mouth" (id.).

The subjects represented are quite varied and numerous. Depending on the periods and the areas, their relative proportions may change hugely. For example, animals, as we have seen, are less abundant at some Bhimbetka sites than in the Chambal valley and humans are central to Historic paintings.

The diversity of the animals and of the ways to represent them is much greater than what is found in European cave art. Nearly thirty different species were for example identified in the rock art of the Upper Chambal valley (Badam & Prakash 1992). The techniques used to render them are also far from stereotyped: for the for the simplest figures only the outlines may be drawn, or they may be in flat tint with the whole body coloured. A great many animals, however, have a body infilling with sometimes very intricate motifs in the form of parallel lines, grids and all sorts of geometric patterns which make the art distinctive. They may be sexed or not. Sometimes pregnant females have been painted with the foetus showing in a sort of X-ray style. Two (generally red and white) or more colours may be used for the same subject. The animals may be represented in isolation or in herds or in conjunction with humans.

Humans may sometimes be dominant (see above about Bhimbetka) but in any case they are nearly always present even among the earliest paintings. In their case too, variety is the main characteristic, even if they seem to have been given less details than the animals, except for the horse riders and fighters of the later ages (Chakravarty & Bednarik 1997: 69). They may be stick figures and be stiff or, on the contrary, quite dynamic, seeming to be running, dancing, hunting or fighting. Others have double lines for the body and arms and sometimes inner decoration, though far less than is the case with animals. Their heads are rarely detailed, even if they may occasionally sport some headgear. They often wield weapons, such as bows and arrows, shields, variously tipped spears or axes. They are often engaged in activities with other humans (dancing, fighting, having sex, curing the sick, carrying loads, eating, sometimes inside a house or a tent or with animals (hunting), fishing, riding horses, elephants or oxen, driving carts or chariots, drawing ploughs. The abundance of scenes of all sorts in Indian rock art is one of its major and most appealing characteristics.

Various objects, as well as geometric signs, can be represented independently of humans and animals. In Historical times, inscriptions have been used to help establish a chronology. Superimpositions are frequent. "The particular portions of rock were probably sacred parts of shelters or the artists painted upon the old drawings simply to enhance the power of his new pictures. It might be a taboo to erase the old drawings" (Mathpal 1998: 9). Establishing a succession of styles from superimpositions has often been attempted.

As always, dating the art is a thorny problem which has been tackled in various ways, with not completely satisfying results, right from the first discoveries in the 19th century until now. In general, Indian rock art has been divided into three main periods each with (or without) a number of phases. Leaving apart the possibility of Palaeolithic art, which until recently was discarded by a number of scholars and is still being discussed, the "traditional" chronology distinguished the Mesolithic art of the hunter-gatherers, with naturalistic animals, from the Chalcolithic art of the agriculturalists, with the appearance of cattle and chariots, and finally the Historical periods, with an emphasis on fighting (Neumayer 1992). Pandey (1992: 25) brought in the weathering of the art, as, according to him, Mesolithic paintings were invariably patinated, whereas those of the Chalcolithic sometimes were while it was never the case with Historic art.

In addition, Kumar's "fresh attempt" involves three approaches: 1. Classification of rock art on the basis of evolutionary traits visible in the development of forms, motifs, styles, inventions, technology, fauna, and human cognitive and creative abilities. 2. Periodization on the basis of internal evidence from the rock art and rock art sites, and external evidence provided by other scientific disciplines. 3. Establishing antiquity of the rock art by a) indirect dating methods, and b) direct dating methods" whenever they are available (Kumar 2000/2001: 9).

Kumar's new scheme is not really contradictory with the preceding classifications, though he now considers two main groups, separated by the advent of cattle-rearing: I. The Palaeolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. II. The pastoralists and agriculturalists. Each group, though, is subdivided into different phases.

India with its innumerable monuments stands in the top rank of all nations for the importance of its cultural heritage. If this has long been known, Indian rock art, on the other hand, is just starting to achieve the fame that it deserves. In the years to come, much more work will be done on its dating and on registering its innumerable paintings and engravings. The amount and the quality of the work achieved since Vishnu Wakankar began his famed work in Central India are a good omen of what is in store.

BADAM G.-L. & PRAKASH S. 1992. - Tentative identification and ecological status of the animals depicted in rock art of Upper Chambal Valley. Purakala 3, 1/2: 69-79.

BEDNARIK R.-G. 2000/2001. - Early Indian petroglyphs and their global context. Purakala 11/12: 37-47.

BEDNARIK R.-G. 2001. - The oldest known rock art in the world. Anthropologie XXXIX, 2-3: 89-97.

CHAKRAVARTY K.-K. (ed.) 1984. - Rock Art of India. New-Delhi, Arnold-Heinemann.

CHAKRAVARTY K.-K. & BEDNARIK R. 1997. - Indian Rock Art in its Global Context. Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Ltd.

CHAKRAVERTY S. 2003. - Rock Art Studies in India. A Historical Perspective. Kolkata, The Asiatic Society.

CHANDRAMOULI N. 2002. - Rock Art of South India. Delhi, Bharatiya Kala Prakashan.

KUMAR G., PANCHOLI R.-K, NAGDEV S., RUNVAL G.-S., SRIVASTAVA J.-N. & TRIPATHI J.-D. 1992. - Rock Art of Upper Chambal Valley. Part I: Rock Art and Rock Art Sites. Purakala 3, 1/2: 13-55.

KUMAR G. 1992. - Rock Art of Upper Chambal Valley. Part II: some observations. Purakala 3: 56-67.

KUMAR G. 2000/2001. - Chronology of Indian Rock Art: a fresh attempt. Purakala 11/12: 5-35.

KUMAR G. 2002. - Archaeological excavation and explorations at Daraki-Chattan-2002: a preliminary report. Purakala 13, 1-2: 5-20.

MATHPAL Y. 1984. - Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Bhimbetka, Central India. New-Delhi, Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts.

MATHPAL Y. 1985. - Rock Art in Kumaon Himalaya. New-Delhi, Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts.

MATHPAL Y. 1992. - Rock Art Studies in India. In Lorblanchet M. (ed.), Rock Art in the Old World, pp. 207-214.

MATHPAL Y. 1998. - Rock paintings of Bhonrawali Hill in central India: documentation and study. Purakala 9, 1/2: 5-52.

NEUMAYER E. 1983. - PrehistoricIndian Rock Paintings. New-Delhi, Oxford University Press.

NEUMAYER E. 1992. - Rock Art in India. In Lorblanchet M. (ed.), Rock Art in the Old World, pp. 215-247.

PANDEY S. 1993. - Indian Rock Art. New-Delhi, Aryan Books International.

PRADHAN S. 2001. - Rock Art in Orissa. New Delhi, Aryan Books International.

PRADHAN S. 2004. - Ethnographic parallels between rock art and tribal art in Orissa. The RASI 2004 International Rock Art Congress, Programme and Congress Handbook, p. 39.

SHARMA R.-K. & TRIPATHI (eds.) 1996. - Recent Perspectives on Prehistoric Art in India and Allied Subjects. New Delhi, Aryan Books International.

TEWARI R. 1992. - Rock Paintings of Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh. In Lorblanchet M. (ed.), Rock Art in the Old World, pp. 285-301.

WAKANKAR V.-S. 1978. - The Dawn of Indian Art. Ujjain, Bharati Kala Bhawan.

WAKANKAR V.-S. 1992. - Rock Painting in India. In Lorblanchet M. (ed.), Rock Art in the Old World, pp. 319-336.

WAKANKAR V.-S. & BROOKS R.-R.-R. 1976. - Stone Age Painting in India. Bombay, D. P. Taraporewala Sons and Co.