According to archaeological findings, since at least from the second half of the first millennium BCE, the Luo Yue people have lived in small-scale societies in the region encompassing south-western Guangxi and northern Vietnam. Yet, this ethnic affiliation has a weakness that needs to be looked at: if they were indeed the authors of the rock paintings, why was the Zuojiang River valley the only area selected to be decorated? And why was the Huashan mountain particularly chosen to produce the art with the greatest scale, the most grandiose ‘scenes’, and the largest number of images? To answer these questions, it is necessary to understand the cultural context of the art at the time when it was produced, and to analyse the connection between the culture and the location of the rock art sites.

As mentioned above, even though each interpretation of the Huashan rock art has its own evidence and explanation, there is no way to determine the exact meaning behind those ancient images. In this article, I do not intend to compare or argue among the different interpretations proposed by previous scholars. My purpose is to provide a new perspective to view the connection between the Huashan rock art and the Luo Yue people’s cosmology: to see it from the location of the site itself.

In the Zhuang people’s widely accepted origin myth the universe is divided into three sections: sky, water and earth. The thunder god, the water god and the god of ancestors, three most important spiritual beings, respectively dominate the sky, water and earth (Qiu 1996: 73). Therefore, it seems reasonable to make the assumption that the Luo Yue people’s cosmology was also related to the sky, water and earth. This assumption could be also supported by the fact that the various spiritual beings believed to exist by the Zhuang people altogether belong to three main groups: celestial beings and weather phenomena; animals and plants; water phenomena and water predators. The three groups precisely represent sky, earth and water. Besides, it is interesting to notice that in the Zhuang ethnic language today, thunder, cloud, sky and fire are still pronounced very similarly. It is argued that this is influenced by the ancient cosmology of the Zhuang people’s ancestors, who considered the four natural beings as generally the same things (Qiu 1996: 49). Significantly, an analysis of the Vietnamese mythology further strengthens this assumption. The Vietnamese associate their ancestors to Lac Long Quan, a god of the ocean. He came to the Red River Plain and married Au Co, a goddess of the mountain, and they gave birth to one hundred children, who became the first Lac Viet people (‘Luo Yue’ in Chinese) (Taylor 1983: 13). In the myth, the relations among mountain, ocean and plain are clear, as a god from the ocean and a goddess from the mountain met on plain and produced the human race.

In the traditional cosmologies of many ethnic groups in the world, mountains always represent the sky. As Mircea Eliade stated, ‘mountains are the nearest thing to the sky, and are thence endowed with a twofold holiness: on one hand they share in the spatial symbolism of transcendence … and on the other they are the dwelling of the gods’ (Eliade 1958: 99). Besides, mountains are often perceived as the place where sky and earth meet; and a path one can take to pass from one cosmic zone to another (1958: 100). Eliade’s idea is still used in attempts to interpret rock art around the world, such as in Scandinavian (e.g. Helskog and Olsen 1995) and Upper Palaeolithic rock art (e.g. Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988). Ocean or rivers represent the water. For people living in coastal areas, ocean is the broadest form of water. Similarly, inland people view rivers as major symbols of water (Boric 2003: 57). Just as mountains are pathways to the sky world, so may rivers be passages to the underworld. Furthermore, it is easy to understand that plains or fields represent the earth, as on flat lands agriculture is generally more productive and early civilisations flourish more easily. Therefore, the relations among mountain, ocean and plain in the Vietnamese mythology could be seen as evidence demonstrating the significance of the connections among sky, water and earth in the Luo Yue religion. Likewise, it is reasonable to argue that in the Luo Yue religion, mountains, rivers (or oceans), and fields (or plains) were directly related of the cults of sky, water and earth.

Based on the above, it is reasonable to assume that the place where the Huashan rock art site is located was perceived by the Luo Yue people as a special place, a place where intangible forces are manifested in physical aspects of the environment. According to Eliade, the occurrences of unusual features in the landscape that indicate the presence of power can be defined as hierophanies - manifestations of the sacred (Eliade 1958: 14). Hierophanies is the plural form of hierophany, which combines the two ancient Greek words ἱερος (hieros), meaning ‘sacred, holy sign’, and φαίνω (phainô), meaning ‘show, appear’. People are not free to choose the sacred places. On the contrary, people seek for sacred places by the occurrence of unusual signs in the landscape (Eliade 1959: 28).

What are the unusual features in the landscape of the Huashan rock art site? The site is situated on the almost vertical cliff of the Huashan mountain besides the Mingjiang River, which runs a sharp turn from the south-west to the north-west at the foot of the mountain. The painted cliff, surrounded by mountain ranges in the north and east, overhangs the river and faces directly to a flat field on the other side of the river. The river is wide and the water flows gently. Viewed from the opposite bank, the triangular-shaped Huashan mountain is clearly reflected on the surface of the river. As archaeologist Jiang Zhenming noticed during his survey of the site, ‘a dense crowd of red-painted figures thickly dotting the cliff mingled together in red colour, as if they were flaming up under the red glow of the setting sun, jumping on the river, dancing on the cliff and ascending to the sky’ (Jiang 1991: 11).

I propose that the unusual features in the landscapeof the Huashan rock art site were viewed as hierophanies by the Luo Yue people, and then they produced rock art as a way to access the sacred power embodied by the features. According to the detailed description of all the rock art sites distributed in Zuojiang River valley (Qin et al. 1987: 25–122), compared with other painted mountains, only Huashan is of a triangular shape, which provides a solemn ambience as if it peaked directly into the sky. About 68.3% of Zuojiang rock art sites are located beside a turn of the river (Qin et al. 1987: 21). In antiquity, the turns on the watercourse were perceived as the places where the water monsters dwelt as boat wrecks always happened in such places. So the location of the Huashan rock art site probably indicates the Luo Yue’s beliefs concerning the cult of water. Furthermore, while the Huashan mountain is half-surrounded by ridges, a flat field appears on the other side of the river, embraced by the peacefully running water and facing the precipitous cliff directly. In such a sense, the mountain, river and field have been combined in a way the ancient Luo Yue people might have viewed as sacred. Moreover, the orientations of the natural features might have also played a part as to make the place significant. Today, in the Zuojiang River valley, during the rituals devoted to the thunder god asking for rainfall, the animal sacrifices should be placed heading towards the south-east, the direction which the rain is believed to come from (Liao 2002: 74). Even though we cannot assume the Luo Yue’s preference of directions based on the beliefs of the current Zhuang people, it is still reasonable to say that particular orientations manifested in the landscape contributed to the sacredness of the place. In sum, I propose the assumption that the Huashan rock art site was chosen because of its unique landscape, where the mountain, river and field combined together in a certain way as a manifestation of sacred power. It is also reasonable to infer that the Luo Yue people believed that sacred power could be accessed by producing rock art in such a place, and their yearnings would be best received by the gods if rock art was created in such a place.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ The Huashan Rock Art Site

→ Sacred Meeting Place for Sky, Water and Earth

→ Introduction to the Huashan Rock Art Site

→ UNESCO World Heritage Site

→ Huashan Rock Art Gallery

→ Huashan Local Ethnic Culture

→ Huashan Historical Background

→ Religious Beliefs of the Luo Yue

→ Cosmology of Huashan Rock Art

→ 38 Huashan Rock Art Sites

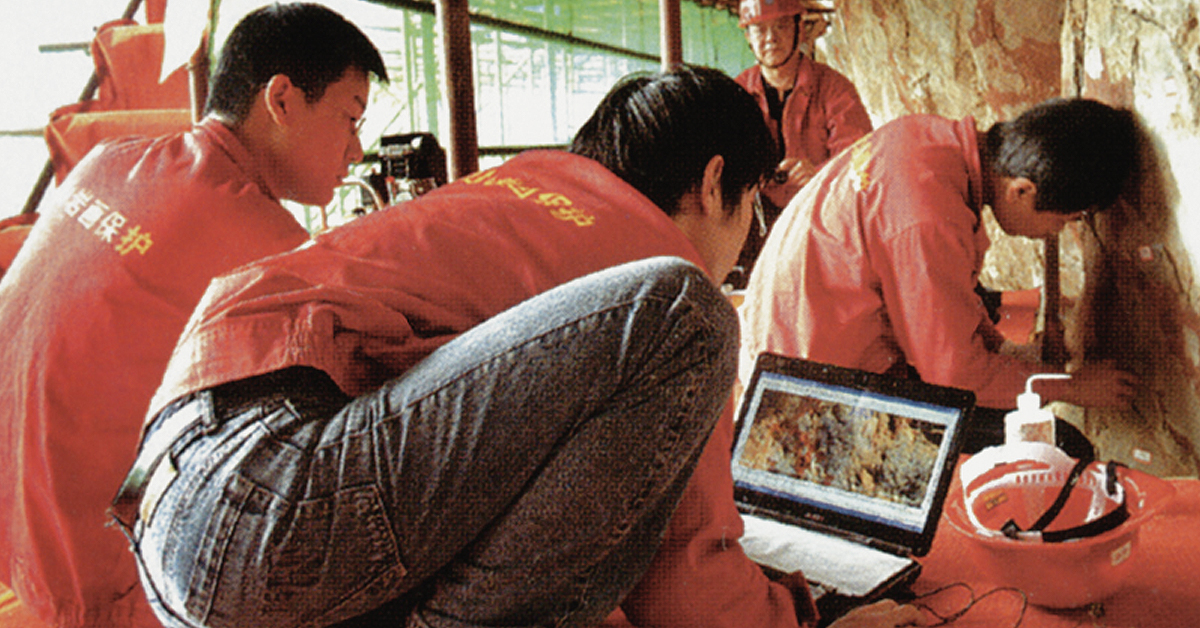

→ Protection of Zuojiang Huashan

→ Wushan Rock Art

→ China Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network