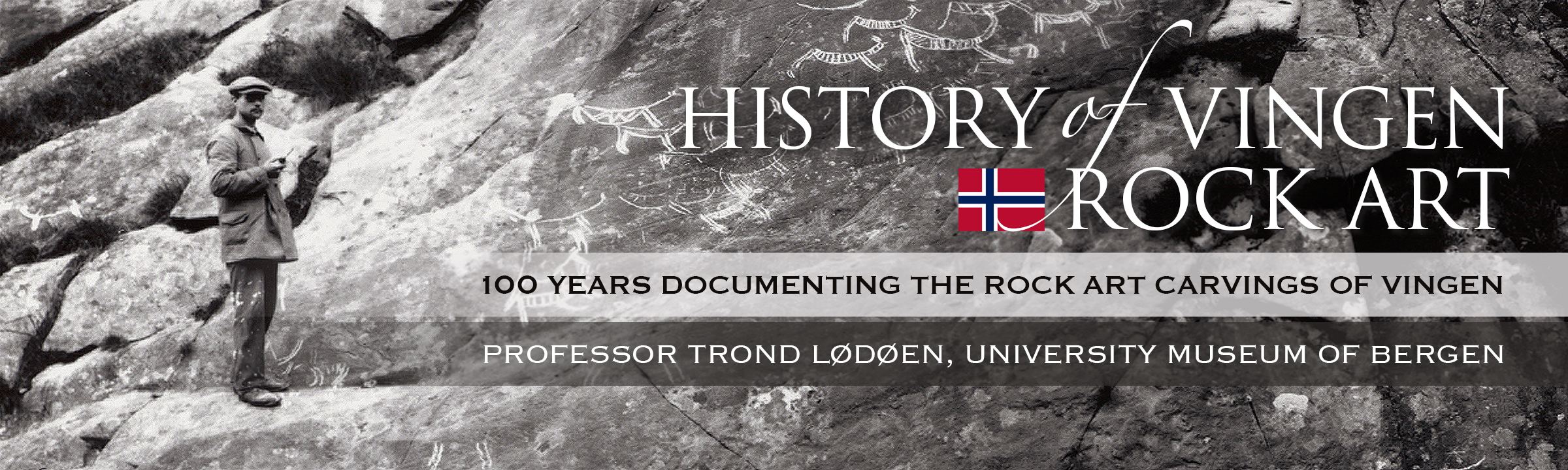

By Trond Lødøen - Associate Professor

Department of Cultural History - University of Bergen

Bing had stayed in Bremanger, in the far north of Sogn og Fjordane to climb the east wall of the Hornelen mountain massif, when he heard about the new discoveries in the area. The climber was also a keen amateur archaeologist who immediately took an interest in the information. Shortly after, he was well received by owner Thue Gullaksen Vingen, who showed a series of animal figures carved into rocky outcrops and solid rocks around a small arm of the fjord just east of Hornelen. Bing could establish that they were prehistoric rock carvings, and was overwhelmed by the images. This inspired the owner, who then announced a number of new discoveries, both lying exposed and revealed under moss and heather.

For Thue Gullaksen Vingen and the local inhabitants, the images had been known of for a long time when Bing visited Vingen, probably already from around 1884, but the information about the carvings was to a small or only modest extent spread on to others. The article by Bing therefore marked a clear turning point for the site and led to a great deal of interest. Already in the same year, representatives from Bergen's Museum were in place and they immediately set about planning how the rock carvings - now numbering many hundreds of figures - could be documented.

The scope had become quite large and the publication was constantly postponed. It was useful for him that Bøe's publication became available, before he could in 1938 publish his own work on Vingen, and as many as 38 other localities under the title 'Monumental art of Northern Europe: The Norwegian Localities'. Barely two years after Hallström's documentation and interpretation was published, the married couple Eva and Per Fett were in the same area to examine some petroglyphs which it seems that neither Bøe nor Hallström had time to examine at the neighboring farm of Vingelven. These are often included in what can be referred to as the Vingen area, obviously part of the same tradition as the other carvings in the area, and are therefore natural to include here. Their work was published in the Bergen Museum's yearbook in 1941 as 'New carvings in Nordfjord: Vingelva and Fura'.

Over the 1970s, interest in Vingen increased among the public. At the same time, pressure from the tourism industry for better accessibility increased. This led to the construction of footpaths between the largest threshing fields, the creation of brochures and the installation of information signs. In connection with this first, several of the carvings were painted because they could be difficult to see for an untrained eye. Parallel to this, one really began to realize that rock art was in the process of weathering away. Now a different type of documentation was put on the agenda – namely mapping of the damage and studies of the condition of the rock art. Hallström and Bøe had already pointed out in the early 20th century that the carvings in Vingen were very comprehensive. Bakka's diaries from the 1960s and early 1970s also confirm the carvings' poor state of preservation. From the mid-1960s onwards, the carvings were also exposed to several cases of ugly vandalism. A number of fields were soiled with marker scribbles and paint, in addition to many figures being damaged with deep and unsightly scratches. The mapping in the 1970s concluded that the condition of the carvings in Vingen was particularly critical and that it was urgent to find countermeasures. This situation, as well as information about many other fields that were in a critical state, led to active research being launched to find the best safeguard and the most suitable conservation methods. The awakening recognition of a large extent of damage also actualized the need for more comprehensive protection than the Cultural Heritage Act was able to fulfill at the end of the 1970s. This led to Vingen being established as a Landscape Conservation Area, however this still did not prevent the locality from being exposed to new cases of vandalism.

During the National Antiquities National Rock Art Project between 1996 and 2005, a new focus was placed on Vingen, where a number of research approaches were carried out to find out what led to the breakdown of the rock and the destruction of the images. During the project, a great deal of work was done to document climate and vegetation development, as well as chemical and biological degradation processes. All previous documentation material also had to be reviewed and compared with the conditions in the terrain. This resulted in intense and long-term searching in the area to rediscover the fields and figures that Hallström, Bøe and Bakka had documented, but which over the years had been covered by thick layers of lichen, overgrown with peat or which were only fragmentarily preserved. Although the three pioneers in Vingen were very careful with the actual documentation of the rock images, it was not always so easy to find out from their location descriptions. Of course, many factors come into play here, among other things, overgrowth of the area must take its share of the blame. Another factor is that the carvings are often found on small and inconspicuous stones for which it is difficult to give a good location in the stone and block-rich Vingen landscape. Searches for the figures that Bøe, Hallström and Bakka had documented led to a further 600-700 figures, so that the scope today is around 2300 figures. But we know for sure that the number will rise in the coming years.

Our contribution is intended to secure Vingen's knowledge potential for future generations, and perhaps contribute to a renewed focus for cultural heritage. Here, the formidable work carried out by Egil Bakka in the 1960s will also be highlighted. The publication in Oldtiden was the prelude to continuous documentation work that has lasted for 100 years, and which we know will continue for years to come. For our part, it has also been useful to harvest the knowledge that has been handed down to us from people who have lived in the area here for a long time, primarily the Vingelven family. What kind of character our contribution will have, we do not want to reveal in detail before it sees the light of day, but the intentions are to collect all relevant research documentation from Vingen and make this available to other researchers and interested parties. We still have professional interests linked to the site, but have long since realized that the place is an inexhaustible source of knowledge about the prehistoric activities in the area. Many questions are still unanswered, but as we see it, it is high time to expose our knowledge to others. Precisely in this way, the professional debate about what Vingen represents can best continue.

The path towards a greater understanding and protection of the petroglyphs of Vingen has been long and tortuous, and the dedicated participants involved have gone to great lengths. But as Trond Lødøen, Associate Professor at the University of Bergen, makes abundantly clear, Vingen presents an inexhaustible source of knowledge concerning the prehistoric activities of this region, and where many questions are still unanswered. Why, therefore, would there be any doubt about securing the future of this irreplaceable prehistoric and sacred landscape?

The recent announcement that the rock art site of Vingen and its surrounding landscape is under threat from the Aksla quarry and Inste Bårdvikneset quay developments defies logic. Vingen is of World Heritage value and one of the largest and best ancient petroglyph sites in Europe, with its diversity and scale and in particular its surrounding natural landscape which is integral to Vingen’s context and one of the reasons the very ancestors of Norway marked the area with rock art thousands of years ago.

→ Vingen Rock Art In Norway - Index

→ Film: Vingen Rock Art in Norway

→ Paul Taçon - Griffith University letter

→ Norway's Vingen Rock Art Petroglyphs at Risk

→ ICOMOS Statement on Vingen

→ Knowing when to back down: The plight of the Vingen rock art site, western Norway

→ Norway preserves world heritage abroad but not in Norway?

→ Vingen - A Century of Rock Art Research & Cultural Heritage

→ History of Vingen Rock Art in Norway

→ Valuing Cultural Heritage

→ Norway's Confusing Messages

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

→ Film: Vingen Rock Art in Norway

by Bradshaw Foundation

20/02/2024 Vingen Recent Articles

NORWAY

→ Knowing when to back down: The plight of the Vingen rock art site, western Norway

by George Nash

4/03/2024

→ Norway preserves world heritage abroad but not in Norway?

by Bradshaw Foundation

20/02/2024

→ Valuing Cultural Heritage

by Ben Dickiins

20/02/2024

→ Norway's Confusing Messages

by Peter Robinson

20/02/2024

→ Paul Taçon - Griffith University letter regarding the Aksla quarry and Inste Bårdvikneset quay developments in Norway

by Paul Taçon

13/02/2024

→ Norway's Vingen Rock Art Petroglyphs at Risk

by Rock Art Network

13/02/2024

→ Professor Benjamin Smith President, ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Rock Art calls for an immediate review of the decision to allow a rock quarry and a shipping quay to be built at one of the most significant rock art sites in Europe: Vingen.

by Rock Art Network

8/02/2024

→ Vingen - A Century of Rock Art Research & Cultural Heritage

by Trond Lødøen / Ben Dickins

6/02/2024

→ History of Vingen Rock Art in Norway

by Trond Lødøen

1/01/2018

→ Knowing when to back down: The plight of the Vingen rock art site, western Norway

by George Nash

4/03/2024

→ Norway preserves world heritage abroad but not in Norway?

by Bradshaw Foundation

20/02/2024

→ Valuing Cultural Heritage

by Ben Dickiins

20/02/2024

→ Norway's Confusing Messages

by Peter Robinson

20/02/2024

→ Paul Taçon - Griffith University letter regarding the Aksla quarry and Inste Bårdvikneset quay developments in Norway

by Paul Taçon

13/02/2024

→ Norway's Vingen Rock Art Petroglyphs at Risk

by Rock Art Network

13/02/2024

→ Professor Benjamin Smith President, ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Rock Art calls for an immediate review of the decision to allow a rock quarry and a shipping quay to be built at one of the most significant rock art sites in Europe: Vingen.

by Rock Art Network

8/02/2024

→ Vingen - A Century of Rock Art Research & Cultural Heritage

by Trond Lødøen / Ben Dickins

6/02/2024

→ History of Vingen Rock Art in Norway

by Trond Lødøen

1/01/2018

Friend of the Foundation

→ Knowing when to back down: The plight of the Vingen rock art site, western Norway

by George Nash

4/03/2024

→ Norway preserves world heritage abroad but not in Norway?

by Bradshaw Foundation

20/02/2024

→ Valuing Cultural Heritage

by Ben Dickiins

20/02/2024

→ Norway's Confusing Messages

by Peter Robinson

20/02/2024

→ Paul Taçon - Griffith University letter regarding the Aksla quarry and Inste Bårdvikneset quay developments in Norway

by Paul Taçon

13/02/2024

→ Norway's Vingen Rock Art Petroglyphs at Risk

by Rock Art Network

13/02/2024

→ Professor Benjamin Smith President, ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Rock Art calls for an immediate review of the decision to allow a rock quarry and a shipping quay to be built at one of the most significant rock art sites in Europe: Vingen.

by Rock Art Network

8/02/2024

→ Vingen - A Century of Rock Art Research & Cultural Heritage

by Trond Lødøen / Ben Dickins

6/02/2024

→ History of Vingen Rock Art in Norway

by Trond Lødøen

1/01/2018

Friend of the Foundation