by Peter Robinson

Editor, Bradshaw Foundation

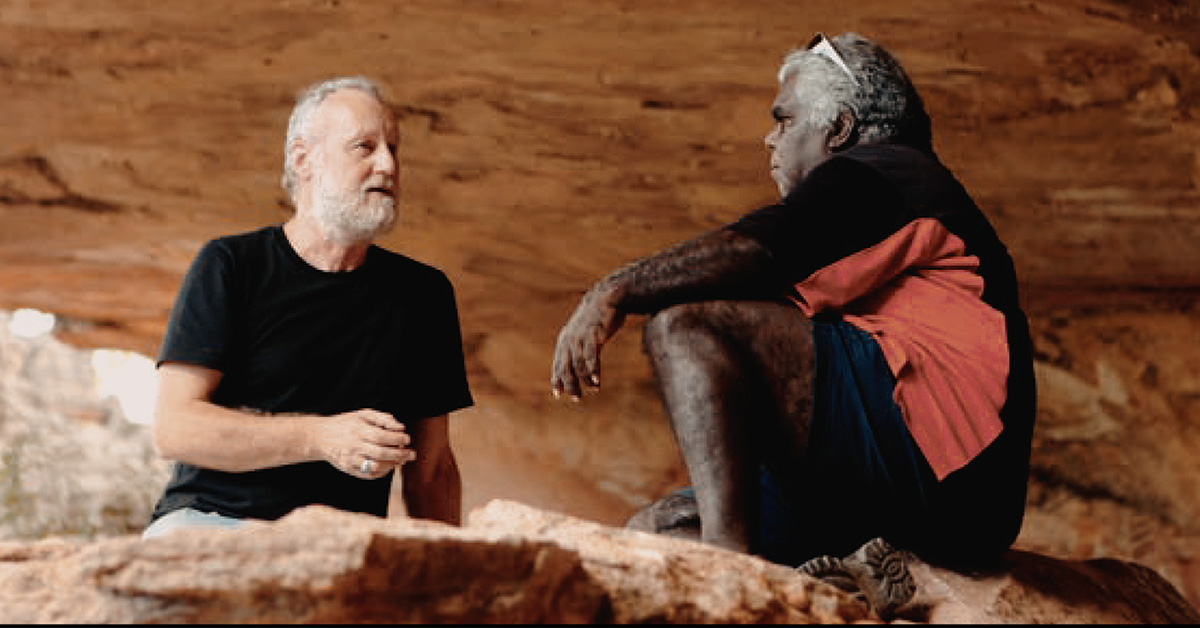

Two recent articles on the Rock Art Network website highlight the importance of working with indigenous communities when understanding, recording and preserving rock art. One article - 'Exploring the wonders of cave art in Australia' - was based on a radio interview with Professor Paul S.C. Taçon, ARC Australian Laureate Fellow (2016-2021), Chair in Rock Art Research and Professor of Anthropology and Archaeology, Griffith University, Australia & Director, The Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit (PERAHU), joined by Professor Josephine McDonald, Rio Tinto Chair of Rock Art Studies, ARC Future Fellow (2011-2016), Director of the Centre for Rock Art Research & Management at the University of Western Australia, and First Nations colleague Wayne Brennan, archaeologist & Interpretive Officer at National Parks and Wildlife Service. The conversation covered fundamental aspects of rock art, perhaps the most salient of which was the importance of the art within the indigenous communities and the ensuing dialogue with scientists. Both Paul and Josephine are members of the Rock Art Network.

Another article by Tom McClintock, Research Associate at the Getty Conservation Institute and a member of the Rock Art Network - 'Studying the Source of Dust Using a Simple and Effective Methodology' - describes his research in Australia in conservation and site management. Here he was enlisted by Njanjma Rangers, an indigenous ranger group dedicated to natural and cultural resource management based in the community of Gunbalanya in Australia’s Northern Territory.

Conversations I have had with all members of the Rock Art Network reinforce this point. So it was interesting to observe a deviation from the rule in recent press coverage, this time in the guise of Western-centrism and Eurocentrism.

Last year I was contacted by Judith Trujillo Téllez, a Colombian archaeologist working with the Group of Investigation of Indigenous Rock Art (GIPRI), to collaborate with their research and dissemination of the rock art of La Lindosa Guavire in the Chiribiquete National Park.

We duly posted a story on our Latest News describing the rock art and how it was being studied by archaeologists and anthropologists, and the implementation of preservation measures by the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History (ICANH) declaring the Serranía La Lindosa a protected Archaeological Area of Colombia (AAP), covering an area of 893 hectares. With La Lindosa, Colombia now has 21 protected archaeological areas.

Clearly, the rock art of this region is very important, confirmed by the fact that it was given UNESCO World Heritage status: Chiribiquete National Park: “The Maloca of the Jaguar”. Date of Inscription 2018, and No. 41 on 'Rock Art on UNESCO’s World Heritage List' by Pilar Fatás Monforte, Directora Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira. We look forward to working with Judith and her colleagues from GIPRI.

However, later in the year, reputable newspapers and magazines in Europe and in other western cultures ran articles with titles such as 'Sistine Chapel of the ancients' and 'Rock art discovered in remote Amazon forest', claiming the glamorous discovery of one of the world’s largest collections of prehistoric rock art 'in an as-yet unnamed site' deep in the Amazon rainforest.

Sure enough, there was an immediate response on social media. Colombian researchers replied with comments such as “We need to have an awkward conversation", "a clear example of how scientific discovery is colonised and monopolised", "Colombians have known, researched and fought to preserve this site for decades", "In principle, it would not be a 'discovery', as these had already been warned [sic] and investigated for more than 70 years (Gheerbrant, 1952; Botiva, 1986; Urbina, 2015; etc)" and "indigenous communities that even today (after millennia) have a direct connection with those sites".

Simon Sebag Montefiore points out in his new book 'Written in History; Letters that Changed the World' that Christopher Columbus, who was famed for the discovery of America, that in fact 'it was only new to Europeans: civilisations unknown to Europe had thrived there for millenia.' Lessons have been learnt from the past. One is reminded of the early interpretation of the White Lady of Brandberg in Namibia by Abbe Henri Breuil who declared that the central figure was a depiction of a graceful and poised young woman of Minoan or Cretan origin whose presence was explained by an ancient Mediterranean visit to this southerly realm of Africa; a tracing of the White Lady by Harald Pager clearly shows 'her' to be a man. So I always find it odd when such lessons seem to be forgotten every now and then.

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation