by Nicholas Hall

Senior Heritage Advisor, Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai, New Zealand

The management of rock art sites in so many locations around the globe struggles with lack of resources, new development pressures, disengagement of and between stakeholders, absence of sustainable mechanisms to deliver management programs, and lack of access to expertise in understanding social, cultural, and technical issues. In these contexts, with which we are all so familiar, what is the way forward? How can the management of rock art sites improve, particularly in relation to the human dimensions that are so often at the heart of many management issues?

The answer lies in upgrading the toolbox we utilize to address these problems. First, good planning is required and, second, there needs to be a sustainable management mechanism that utilizes planning and tackles the ongoing challenges of evolving circumstances. A management mechanism needs to be sustainable over a period of time, be responsive, be adaptive to changing personnel, and have good external connections and access to support and resources.

The document Rock Art: A Cultural Treasure at Risk (Agnew et al. 2015) sets out four pillars of rock art conservation policy and practice, of which effective management systems and community involvement are two. This paper addresses both of these pillars, calling for more attention to participatory planning that addresses the fundamental involvement of local communities and Traditional Owners.

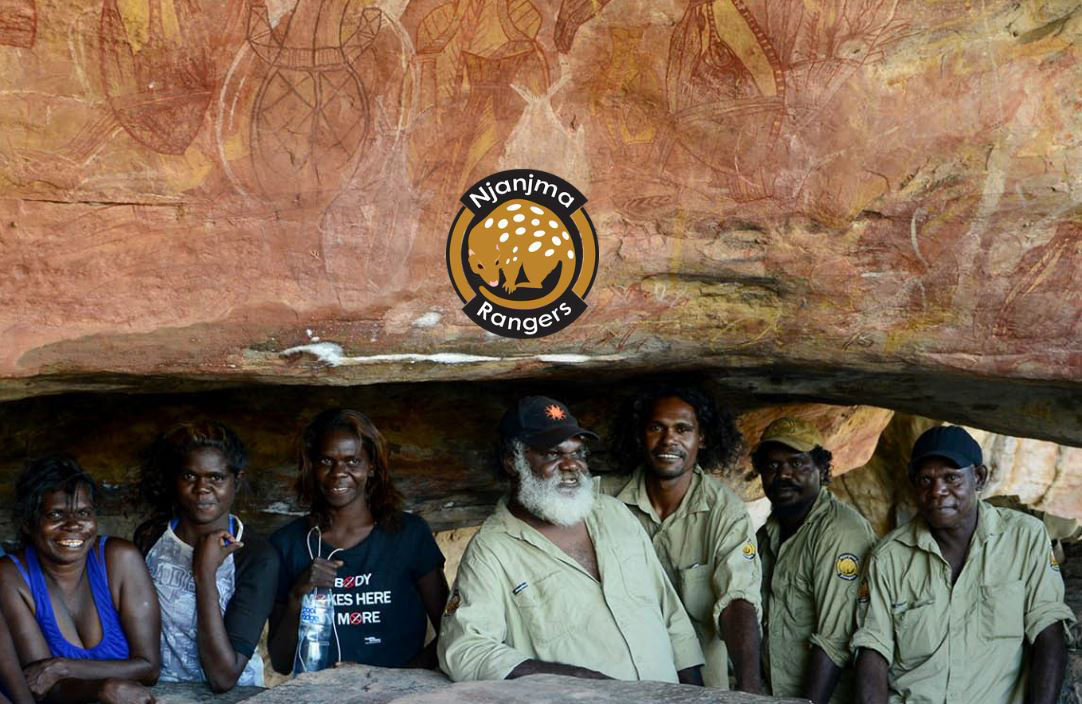

The need for different management paradigms requires us to look at different models, experiment with the constitution of different structures, and investigate how sustainability can be better supported. To address these issues, we can perhaps learn from developments in Australia where Aboriginal ranger groups are playing an increasingly important role in managing landscapes that contain significant quantities of rock art sites. From the outset, this arrangement sets up different contexts: it is a broadacre landscape approach to rock art conservation; local Indigenous people take a primary role; there is a need for stronger and more natural integration of cultural and western knowledges; and there is a need for planning resourcing and works on a sustainable basis.

Experience around the world has demonstrated that unless Indigenous and local communities have the capacity to engage in the decision-making process that affects them, their voice and interests risk being undervalued and sidelined and at worst remaining invisible and ignored. Some of the most powerful and effective means of inserting Indigenous knowledge into the political, administrative, and resourcing arenas are through rendering knowledge in maps (Pedrick 2016), mobilizing Indigenous knowledge assets for economic purposes such as tourism (Cole 2006), and generally asserting Indigenous knowledge within planning processes (Walker, Jojola, and Natcher 2013).

Participatory planning is not new, but the means to implement it more frequently and effectively requires increasing focus on the role of facilitation, building capacity at the local level, and embedding participatory planning processes and outcomes into the structures of land and heritage management. In the case of economic development, such as cultural tourism, participatory planning is a means to develop a tourism “product” in a way that is consistent with cultural, environmental, and tourism industry requirements. Participatory planning is an important tool to help mediate the complex issues of cultural politics, potential impacts, and potential benefits, and to see more creative cultural tourism products developed. It must be a part of the toolbox we can use to manage rock art sites effectively.

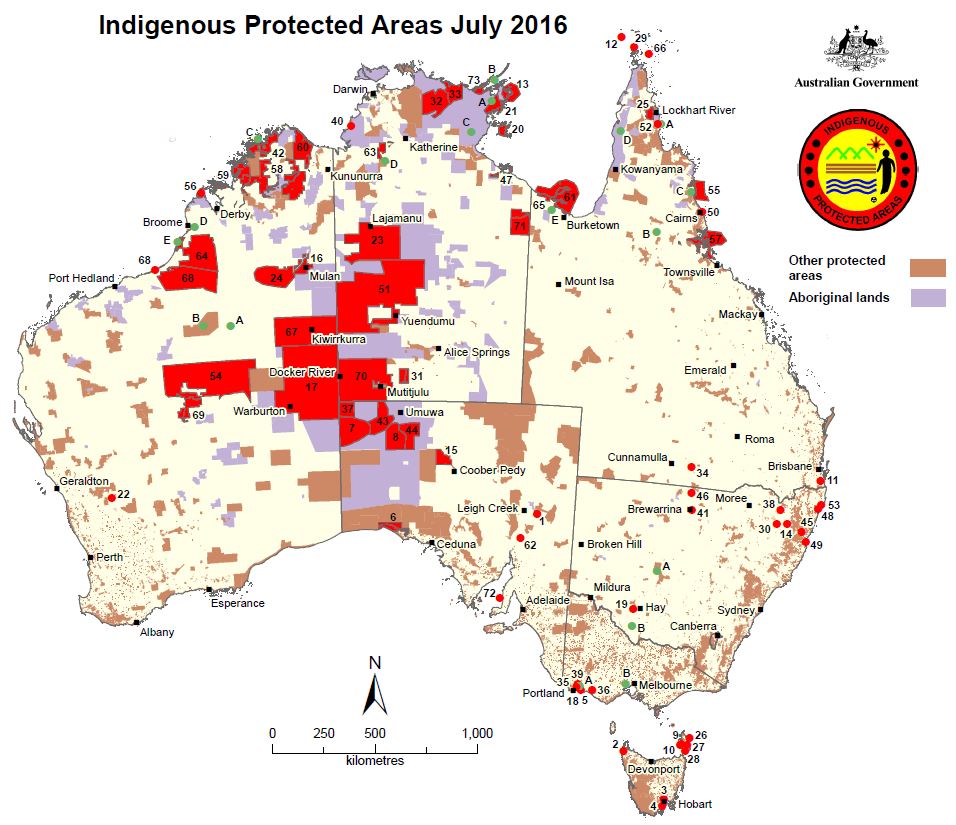

The IPA program enables Indigenous owners of land to enter a voluntary agreement with the Commonwealth government to protect biodiversity—the animals, plants, and other species that call the IPA home—and to conserve the area’s cultural resources, like sacred sites and rock art. Since the first IPA was declared in 1998, IPAs have grown to become a key part of Australia’s National Reserve System, now consisting of over 40 percent of the total area of land in the system.

Both the IPA and WoC programs have gained considerable momentum over the last two decades through clear evidence of their effectiveness and ongoing support from the Australian government and increasingly through private sector and philanthropic contributions. In 2015 a lobbying campaign was formed to argue for the positive impacts of the program in the face of political uncertainty of ongoing financial support. The campaign was very effectively organized and delivered through its online platform (http://www.countryneedspeople.org.au/).

In Aboriginal ranger programs across the country, natural resource management is the dominant influencing paradigm and the majority of funded activity is directed at the management of natural environmental values. The Australian government supported the import of a planning system, Conservation Action Planning (CAP), developed in the US by the Nature Conservancy, which focused on identifying threats and setting targets. Over time a much stronger cultural emphasis has emerged in the plans developed underpinning the ranger program activities and IPAs. In many cases, these management plans have come to be referred to as “Healthy Country” plans, reflecting an interest from many groups not only in environmental health but also in linking community cultural and social health to the programs as well. This aligns better with Indigenous worldviews and the government’s policies to improve Indigenous health, education, and well-being.

Raising the profile of rock art and cultural heritage management in these largely natural heritage-dominated programs needs a structured input into Healthy Country plans, funded program deliverables, and annual budget processes. This requires a sound planning approach and conversion into achievable and fundable program goals based on the conservation and social values identified.

In many areas of Australia containing large quantities of rock art sites, Aboriginal ranger programs provide the platform and opportunity to make significant differences in the way that rock art sites are protected and managed. This can be achieved in a broadacre landscape setting in which the social connections between people and places can be better recognized, important landscape-scale threats can be addressed, and systems can be put in place to better allocate resources based on priority management needs.

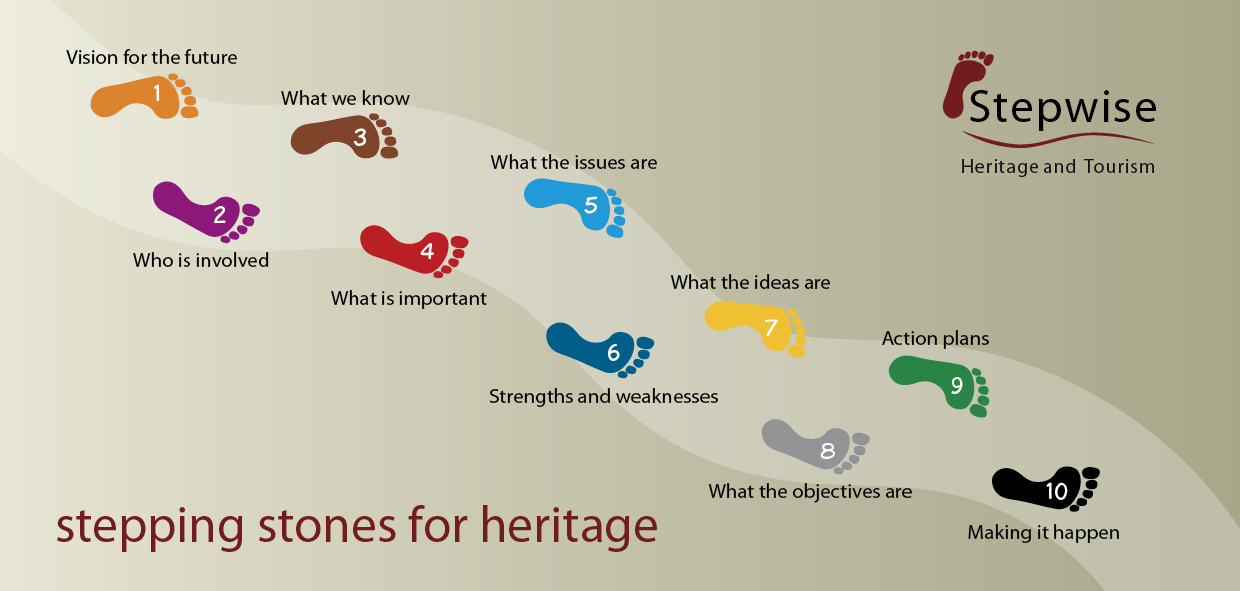

Stepping Stones is a participatory planning tool that has two forms: Stepping Stones for Heritage, used for planning for values-based management in natural and cultural heritage management, and Stepping Stones for Tourism, used to ensure that heritage values are protected in developing tourism proposals and projects. The two tools are mutually reinforcing and can be used in conjunction or sequentially.

There are five key underpinnings of the Stepping Stones approach:

- 1. Creating space – for discussions and to allow Indigenous worldviews to be integrated.

- 2. Shared points of communication – to enable exchange and use of different forms of knowledge.

- 3. Informed decision making – for people to be informed about decisions that affect them.

- 4. Learning by doing – to enable capacity building based on real-life experiences.

- 5. Creating action pathways – manageable step-by-step tracks that value and encourage self-reliant community action.

The Stepping Stones process is a form of values-based management that follows the tenets of the Burra Charter approach (Australia ICOMOS 2013) in placing the identification of values in a primary position and then using an understanding of values to guide management policies and programs. There is a convergence and synergy here of the heritage methodology with the methods proposed for more inclusive planning with local and Indigenous communities that emphasize an attention to culturally appropriate processes (Marika et al. 2009) and means of forging stronger governance arrangements and partnerships (Davies et al. 2013) and improved recognition of the cultural contexts and worldviews of local communities. Others looking to reclaim agency for Indigenous people in planning have called for a values-based approach to be used where there is a greater focus on values in Indigenous terms as the foundation for the transfer of meaning (Walker et al. 2013, 468).

Importantly, Stepping Stones is a facilitated activity that can be used in a range of different contexts to assist in the preparation of plans where a high level of stakeholder and local community ownership or engagement is required. It can be used to develop plans for individual heritage sites, groups of sites, and protected areas, as well as plans for the development of enterprise activity, such as tourism product development plans or business plans. For rock art sites, there are examples of the application of Stepping Stones in each of these contexts.

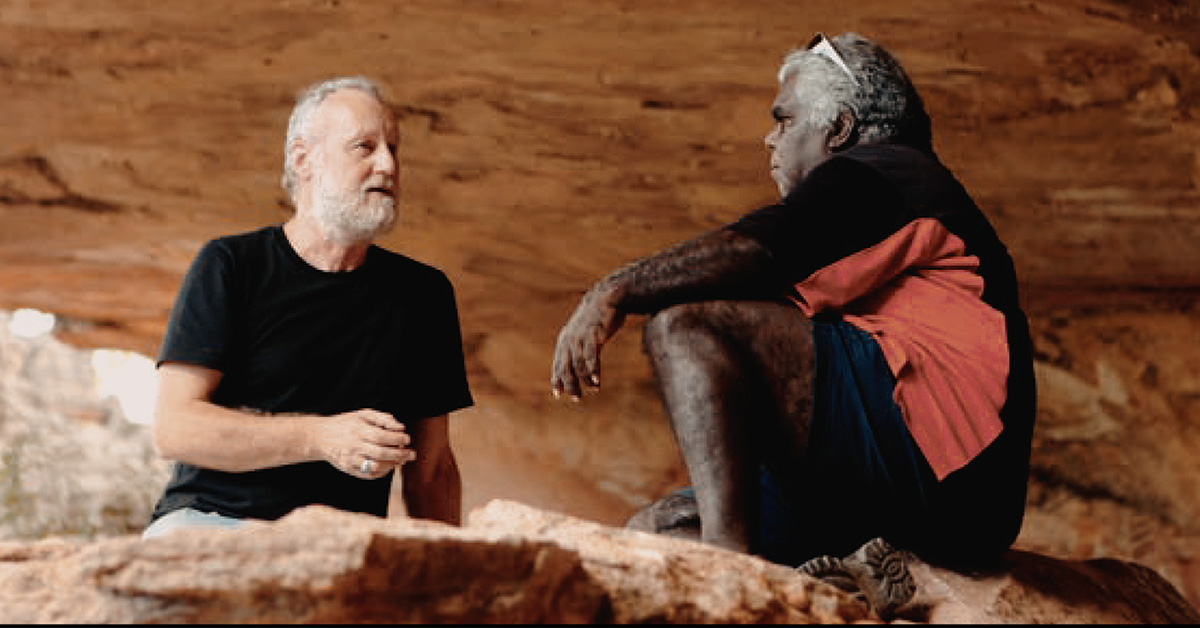

Training and capacity building is usually intimately connected to Stepping Stones activities. In many cases, it is included within the main facilitated activities or immediately following them. As a facilitated activity, the role of the facilitator is crucial in having skilled individuals who can adapt to the planning process and alter their personal position fluidly between that of facilitator, collaborator, analyst, independent expert, and trainer. In this case, the role is not that of a purist content-free facilitator but ideally that of an individual who has content or expert knowledge to contribute. Facilitators are, most important, the protectors of the process with a primary responsibility to ensure its integrity and where necessary to steer group energies to productive ends in relation to it. They are also there to support decision makers and informed consent at all levels.

Finding suitable people with the background, skills, and aptitude to take on this task is not easy, but encouraging greater use of participatory planning and encouraging young professionals to gain more diverse skills and experience in facilitating activities, projects, and planning in varied cultural contexts is an important start.

While there is a tendency in tertiary studies to promote deep disciplinary specialization, we also need to ensure the heritage management process continues to be foregrounded in professional practice training. For Australian rock art at this point in time, we certainly need more skilled people who can work in the space of supporting Aboriginal ranger groups in their work, providing well-informed advice, and facilitating sustainable partnerships and programs. How to deliver better support services for Aboriginal ranger programs is the next immediate need and challenge in Australia. Part of this will be creating new mechanisms for longer-term sustainability in management partnerships and programs that benefit from research collaboration as well as ongoing access to expert advice and support. Within the Australian context, we need several networked locales where this potential is demonstrated to other ranger groups. In the international arena, these demonstration locales could offer education to others interested in establishing forms of community-based management systems.

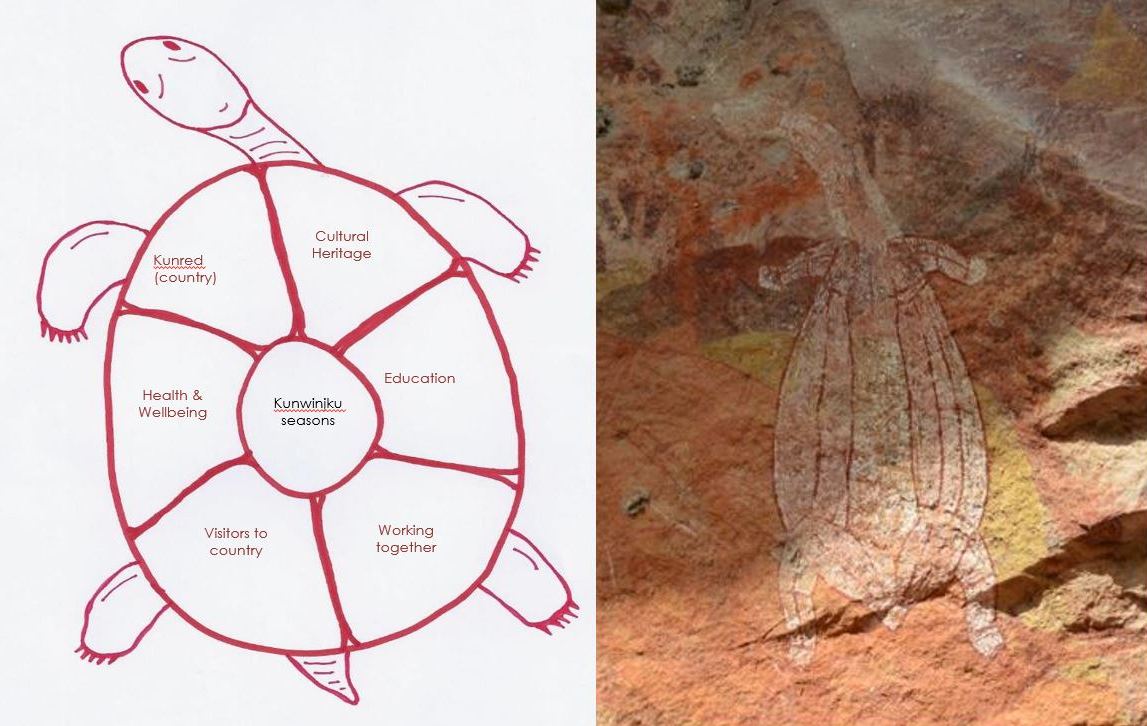

The areas of value around which the Njanjma Rangers program is based, depicted in the shape of the long-neck turtle.

Commencing operations in 2014 through an interim plan that was enough to convince the Australian government to provide WoC-funded ranger positions, the first major task of the new ranger group was to develop a full plan for their operations over a four-year funding period (2015–18). This planning was undertaken using the Stepping Stones approach via participatory planning sessions on country and other sessions over a six-month period. From the outset, clan members have wanted a strong component, if not the lead component, to be the work on rock art sites. This includes high-priority protection work, ensuring that the value of rock art within the community is maintained and enhanced and that the story of their country and its rock art is shared widely. Njanjma Rangers chose a term for their rock art work: Kunwardde bim karridurrkmirri; literally, working “for” rock art (fig. 3).

The planning activities moved through the ten Stepping Stones steps, a strong vision was collectively written, and time was spent discussing and clarifying the important value that the rangers’ task was to protect. Participants chose to reflect the values within the shape of a long-neck turtle, an image that also appears in the local rock art (fig. 4). Facilitated sessions also focused on identifying issues and threats to values and on priority activities within each area. Documentation of each of the steps in the process was then prepared and presented as the Njanjma Rangers Healthy Country plan, which was used as the basis for funded activities for the agreements with the Australian government for the WoC ranger positions.In terms of the rock art components of Njanjma activities, emphasis has been placed on coordinating the various activities associated with immediate threats of fire and the impact of dust from the road in Red Lily Lagoon and of coordinating efforts of the various researchers working on rock art in the region. Funding was sourced to develop a data management system to coordinating legacy data and new data collected by rangers. Additional funding was secured to develop and test a specialist rock art management system, work that is currently still under way. The components of the Njanjma rock art management program and the suite of partners that support the work have been presented on a website (www.njanjmabim.net) to ensure that the many intersecting areas of activity are brought to people’s attention and to use as the basis for sharing with others about rock art management. The link to the Getty document Rock Art: A Cultural Treasure at Risk is made explicit as a key resource for informing the Njanjma program and improving rock art management programs in general. Very soon the next participatory planning cycle will re-engage to check priorities and focus the activities of the rangers in the period post-2018 to ensure there is continuity of WoC funding as well as other sources of funding and support.

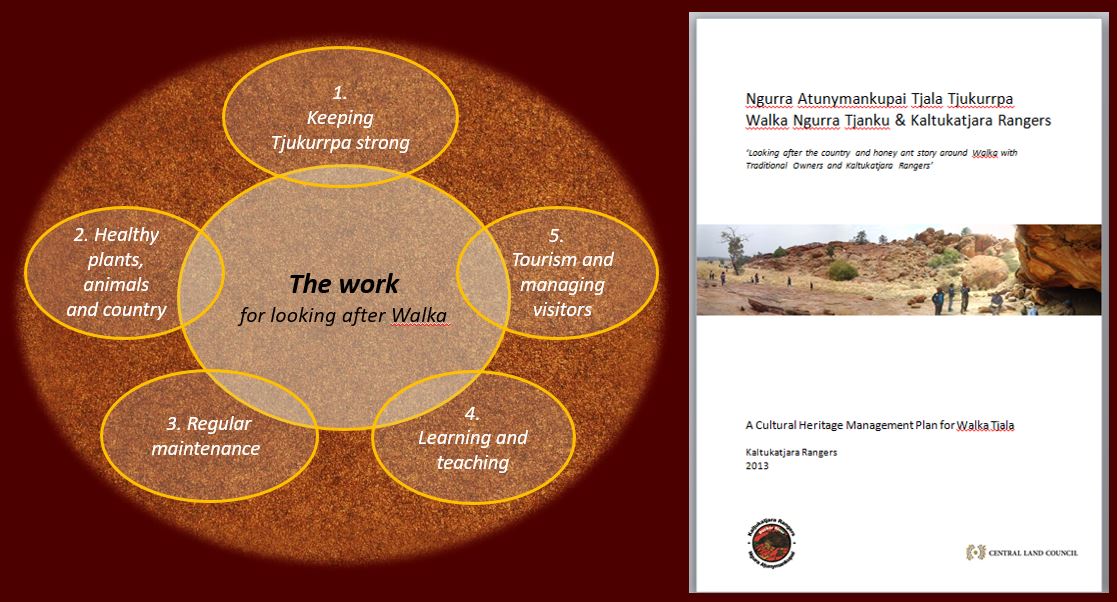

From here, key principles for tourism management and development and high-priority activities were identified. One of the high-priority projects identified by Traditional Owners was tours that included visits to prominent Tjukurpa (Anangu law) places, one of which contains rock art associated with the activities of the tjala (honey ant) ancestor. The rangers and Traditional Owners were engaged initially to do a conservation management plan (CMP) for this site with the help of a facilitator (rather than a consultant or expert). This was done using the Stepping Stones for Heritage. A plan was prepared covering five main areas for the rangers to focus on (fig. 6).

Management plan for the Walka site, covering five areas of focus for the rangers.

These various activities, guided by the use of the participatory planning method, provided a stronger and more informed input to the plan of management that was finalized for the IPA (Central Land Council 2015).

This case study illustrates a number of important aspects about the potential of achieving better outcomes for rock art management working through Aboriginal ranger groups. First, using the participatory process over a period of time in many activities enabled Anangu to be more informed and make more considered and strategic decisions. The responsibility for the process is not externalized to outside experts and emphasizes and helps resource a local sustainable management arrangement. The processes reflected cultural modes of operation, Anangu ways of thinking, and appropriate ways of reflecting highly significant information. Overall the process seeks to build the conditions for greater local agency and responsibility while linking this to external information and connections that will help.

The experience of Aboriginal ranger programs and IPAs in Australia provides important demonstration cases for different forms of rock art management where the locus of operation of custodianship moves toward supporting sustainable local activity that is less dependent on, but orchestrated in synergy with, external agency and expert activity.

The success of the movement for Indigenous and local community management of landscapes and heritage sites that has occurred in Australia (and other locations such as Canada) could be applied more broadly. Where there is recognition of traditional forms of land title for Indigenous communities, forms of supported land management roles are always possible. In places where there are much more complex historical layers of cultural flux, greater emphasis can be put on developing suitable contemporary custodial arrangements. For communities involved in either case, the outcomes of pride in being recognized as responsible for caring for heritage and the life and work skills that derive from this role cannot be underestimated in value. The link between rock art and the broader cultural health and well-being of groups provides a benefit for communities beyond that of the physical protection of rock art.

How we provide support to programs such as Aboriginal ranger groups will be a key test for the future. Looking ahead, we should encourage and support greater use of basic heritage methodology and participatory methods as a fundamental part of the toolbox for managing rock art. Using methods that encourage stakeholders to walk “hand in hand” and take it “step by step” will lead the way to more sustainable structures for collaboration between local communities, experts, researchers, and agencies that help achieve better outcomes for rock art.

Agnew, Neville, Janette Deacon, Nicholas Hall, Terry Little, Sharon Sullivan, and Paul S. C. Taçon. 2015. Rock Art: A Cultural Treasure at Risk: How We Can Protect the Valuable and Vulnerable Heritage of Rock Art. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/rock_art_cultural

Australia ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites). 2013. The Burra Charter: The Australian ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. http://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf

Central Land Council. 2015. Ngura Nganampa Kunpu Kanyinma = Keep on Looking after Our Country Strongly: Katiti-Petermann Indigenous Protected Area Plan of Management. Alice Springs, NT: Central Land Council. http://www.clc.org.au/files/pdf/FINAL_CLC_KP_ManagementPlan2015webversion.pdf

Cole, Stroma. 2006. Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 14 (6): 629–44.

Davies, Jocelyn, Rosemary Hill, Fiona J. Walsh, Marcus Sandford, Dermot Smyth, and Miles C. Holmes. 2013. Innovation in management plans for Community Conserved Areas: Experiences from Australian Indigenous Protected Areas. Ecology and Society 18 (2): 14. https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol18/iss2/art14/

Marika, Rarriwuy, Yalmay Yunupingu, Raymattja Marika-Mununggiritj, and Samantha Muller. 2009. Leaching the poison: The importance of process and partnership in working with Yolngu. Journal of Rural Studies 25 (4): 404–13.

Pedrick, Clare. 2016. The Power of Maps: Bringing the Third Dimension to the Negotiation Table. Wageningen: Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation. http://publications.cta.int/media/publications/downloads/1943_PDF.pdf

Walker, Ryan Christopher, Theodore S. Jojola, and David C. Natcher, eds. 2013. Reclaiming Indigenous Planning. McGill-Queen’s Native and Northern Series. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Web Pages

Australian Government. 2017. “Indigenous Rangers: Working on Country.” https://www.dpmc.gov.au/indigenousaffairs/environment/indigenous-rangers-working-country

Njanjma Rangers and Stepwise Heritage and Tourism. 2017. “Kunwardde Bim Karridurrkmirri = Working for Rock Art.” http://www.njanjmabim.net/

Outback Australia Conservation. 2015. “Country Needs People Campaign.” http://www.countryneedspeople.org.au/

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

by

George Nash

5/09/2024 Recent Articles

→ Sigubudu: Paintings of people with guns in the northern uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation

by Aron Mazel

22/07/2024

by Richard Kuba

13/06/2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

8/03/2024

by Rock Art Network

6/02/2024

by Rock Art Network

14/12/2023

by Sam Challis

5/12/2023

by Aron Mazel

30/11/2023

by Sam Challis

21/11/2023

by Sam Challis

15/11/2023

by Sam Challis

10/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

6/11/2023

by Rock Art Network

3/11/2023

by Aron Mazel

2/11/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/09/2023

by Paul Taçon

24/08/2023

by Aron Mazel

13/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

5/06/2023

by Paul Taçon

15/03/2023

by George Nash

14/03/2023

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

10/02/2023

by George Nash

01/02/2023

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak, Pilar Fatás Monforte

29/11/2022

by Aron Mazel, George Nash

21/09/2022

by Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Ursula K. Frederick, Jo McDonald

07/07/2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

26/07/2022

by Paul Taçon

20/07/2022

by David Coulson

16 June 2022

by Paul Taçon

25 April 2022

by Noel Hidalgo Tan

20 April 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

14 March 2022

by Carolyn Boyd & Pilar Fatás

02 March 2022

by David Coulson

07 February 2022

by Johannes H. N. Loubser

06 February 2022

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

05 February 2022

by Aron Mazel

28 January 2022

by Aron Mazel

8 September 2021

by David Coulson

17 August 2021

by Ffion Reynolds

21 June 2021

Friend of the Foundation