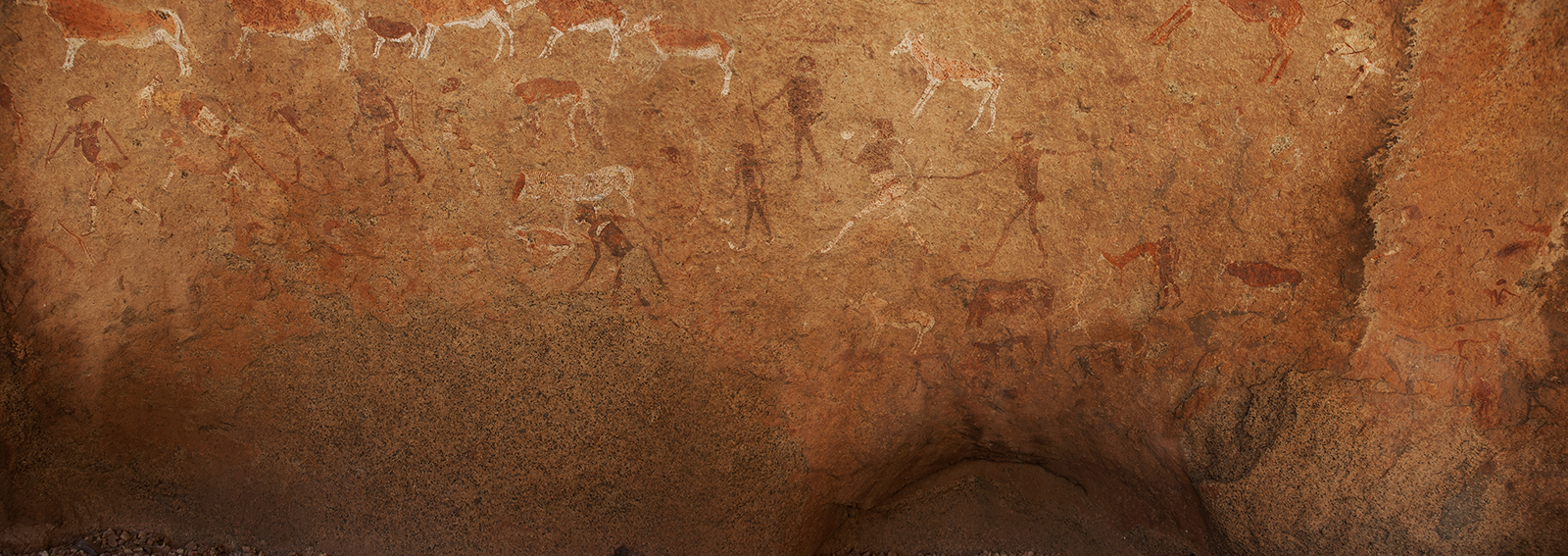

The Brandberg is a site of great spiritual significance to the Damara San (Bushman) people. Regarding rock art, the most famous site is the so-called White Lady' rock painting, located on a rock face with other artwork under a small rock overhang, in the Tsisab Ravine at the foot of the mountain. The Brandberg Mountain, including the higher elevations, contains more than 1,000 rock shelters, with an estimated 45,000 rock paintings.

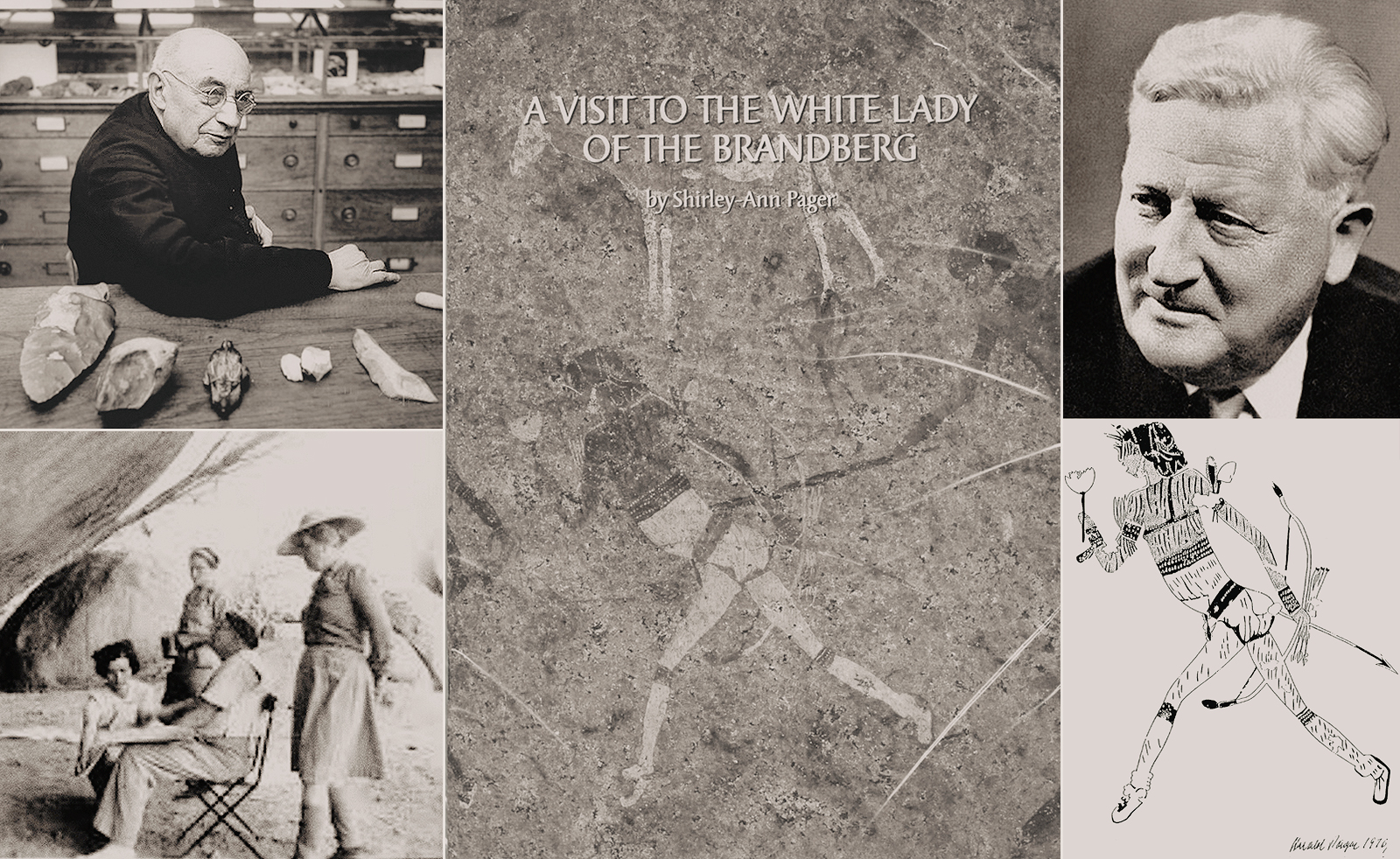

Most of the rock paintings of the Brandberg have been painstakingly documented by Harald Pager, who made tens of thousands of hand-traced copies. Pager's work was posthumously published by the Heinrich Barth Institute, in the six volume series 'Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg' edited by Tilman Lenssen-Erz.

DNA research has now led scientists to believe that humans originated in southern Africa - in the region now bordering Namibia and South Africa. The San people, hunter-gatherers in this area for thousands of years, are now thought to be the oldest human population on Earth because their genetic diversity (the time it takes for genes to evolve) is the most diverse; they are descended from the earliest human ancestors from which all other groups of Africans stem and, in turn, to the people who left the continent to populate other corners of the planet.

The majority of the Damara, who speak the Khoekhoe language, live in the north-western regions of Namibia. Their original culture was a mixture of an archaic hunter-gatherer culture and herders of cattle, goats and sheep.

Jan G. Platvoet, a researcher of the rock art of the San people and focussing on the Ju/'hoansi based in north-eastern Namibia, states that 'the last remarkable trait of the Ju/'hoansi and other and earlier San societies, was their cultivation of trance memories, trance analysis, and trance pedagogic. These enabled earlier San societies to record their trance experiences in their rock art. In those paintings they have left us with a unique and precious documentation which scholars of religions need to study carefully, in co-operation with archaeologists and palaeontologists, in order to incorporate more firmly this longest of humankind's religious history and iconography into the general history of religions, than has been done so far' (Platvoet. J. G. 1999).

Lewis-Williams therefore suggests that instead of the 'trance' or 'shamanist' hypothesis it should be termed the 'potency explanation': the rock art in San shelters served as the transparent 'veil' between this world and that of 'potency' for the San, in the same way as did the stained glass windows in cathedrals for Christians. Indeed, to the San, rock paintings were 'powerful things in themselves, reservoirs of potency and mental imagery', rather than mere memories of past trance experiences.' (Lewis-Williams J.D. 1996).

Another leading figure in San rock art research, Dr. Ben Smith reiterates that the art was not simply a record of daily life or a primitive form of hunting magic. By linking specific San beliefs to recurrent features in the art, researchers have been able to crack the code of San rock art.

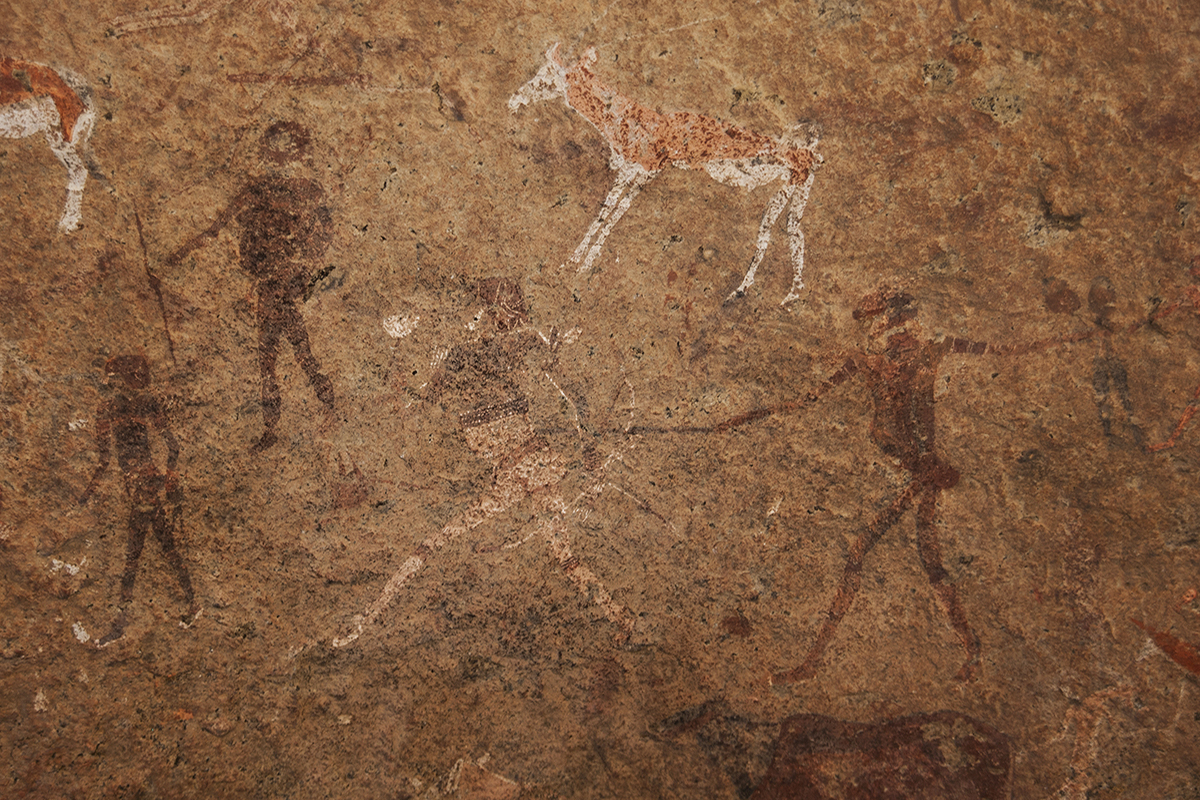

What has been revealed is one of the most complex and sophisticated of all the world's symbolic arts. The art focuses on a particular part of San experience: the spirit world journeys and experiences of San shamans. Thus we see many features from the all important trance dance, the venue in which the shamans gained access to the spirit world. We see dancers with antelope hooves showing that they have taken on antelope power, just as San shamans describe in the Kalahari today. We see shamans climbing up the so-called 'threads of light' that connect to the sky-world. We see trance flight.

To show their experiences, the artists also used visual metaphors such as showing shamans 'underwater' and 'dead'. These capture aspects of how it feels to be in trance. The artists also show their actions in the spirit world, such as their capturing of the rain animal, their activation of potency for use in healing or in fighting off enemies or dangerous forces. But, the art was far from just a record of spirit journeys. Powerful substances such as eland blood were put into the paints so to make each image a reservoir of potency. As each generation of artists painted or engraved layer upon layer of art on the rock surfaces they were creating potent spiritual places.

1917 found the German geologist Reinhardt Maack exploring and surveying the geology of the Brandberg. Forced to stop one night, he took refuge in a rock shelter. In the morning he awoke to a painted panel above him; clearly impressed by the art he made a detailed sketch of the central and surrounding figures. In the late 1920's, a rough copy was made by Fraulein Weyersberg during an expedition to the area by Leo Frobenius. The next character to appear in this story of 're-discovery' materialized in 1929; Abbe Henri Breuil, the leading French prehistorian, visited South Africa where he was able to examine the ethnographic collections in the Anthropology Department, University of the Witwatersrand. Here he saw Maack's original sketch.

In 1947 the Abbe was finally able to visit the decorated panel himself. He too made copies of the painted images in the shelter. Based on his observations, and those of his associate Mary Boyle, he declared that the central figure was a depiction of a graceful and poised young woman of Minoan or Cretan origin, whose presence was explained by an ancient Mediterranean visit to this southerly realm of Africa.

Improbable as this might seem, members of the public believed him: the legend of the White Lady of the Brandberg was born. Today researchers agree that the White Lady is in fact a male figure; both Maack and the Abbe had not noticed the figure's penis. Researchers have also dismissed any European connection.

David Lewis-Williams states that 'she remains a symbol of white influence and domination'; in order to understand why the Abbe's identification was so eagerly accepted, he focuses on the 'role that stereotypes of the San (Bushmen) have played in the formation of colonial conceptions of southern Africa's past. When people view rock paintings or copies of them, they bring with them a load of cultural baggage and prejudice; almost inevitably, they find in the art confirmation for those prejudices' (African Arts, Vol. 29, No. 4, 1996).

For several decades, however, with very extensive research - now centred at the Rock Art Research Institute - a far greater understanding of southern African rock art and the people who made it has emerged.

Breunig and Richter have dated the parietal art in the Brandberg/Daureb from about 2,700 years (terminus antequem; Breunig 1989). The largest amount of work dedicated to the rock art of the Brandberg/Daureb was carried out by Harald Pager, who began his documentation in 1977.

Pager used the name 'Brandberg' since the local Damara name 'Daureb' was hardly established beyond the region. Daureb means 'the burning one' in Khoekhoegowab. Today the indigenous community living below the mountain in the small town of Uis has started to replace the colonial name, such as in Daureb Mountain Guides and Daureb Crafts. There is strong evidence that Daureb is an original name for the mountain among the indigenous population and not a derivation of its European name, even though the German Brandberg also means 'burning mountain'.

Research in the 1960's by J R Harding established that the figure was indisputably southern African and probably male. He writes that 'Bushmen, as well as other people without writing, are informed by word of mouth: and oral information, in the process of being handed down from generation to generation, inevitably becomes distorted, altered in meaning to a lesser or greater extent, confused or lost altogether. And when different peoples live in close proximity, such as the Bushmen and Ovambo, there can be little doubt that interfusions take place in various directions. In this way it is conceivable that tribal memories and traditions, as well as customs and beliefs, can become mixed. Some of these admixtures, together with confused or lost memory traditions and events, I believe to be depicted in all controversial rock-paintings, of which the 'White Lady' fresco is a leading example'.

However, in this case confusion and lost memory traditions were overcome by dedicated research; Harding believed the 'White Lady' painting, taken in its entirety, may have had magico-religious expression. His interpretation was based in part on the ethnographic work of C. H. L. Hahn ['The Native Tribes of South West Africa'] to which he matched details in the painting with an account of the Ovambo 'holy fire' and its use in warfare.

'In times of war when the men went out to meet the enemy, the chief - who was never allowed to leave the tribal area - was represented by a trusted headman whose duty was to lead the army into battle. He was known as the omuliki wita (meaning 'representative and chief of war'). Also accompanying the army was 'a member of a traditional war family' - the ochambati wo shikuni - whose task was to carry an ember from the holy fire and to keep it burning for the kindling of the camp holy fire. The omuiliki wita is not armed like other headman but only carries a bow, a few arrows, one big knob kirri and two small sticks about the size of a lead pencil. The two small sticks were known as omsindilo: they were ignited at the camp holy fire and while burning like candles were waved by the omuiliki wita over the soldiers to make them invisible to the enemy. On the way out, he slackens the string of his bow to such an extent that an arrow cannot be shot from it. This procedure was supposed to cause the strings of the enemy's bows to slacken also and thus to become useless.'

Harding remarked on the non-combatant appearance of the White Lady's weapons - a slackened bow string and a few loosely-held arrows. The White Lady holds in the other hand a burning stick [and not the cup-shaped flower or ostrich egg-shell cup favoured by the Abbe Breuil]. And where the Abbe Breuil argued that the 'five white arrow tips thrust into the arm-band of the White Lady', Harding suggests they represent 'a further supply of small sticks ready for ignition, one after another, when the one held is burnt out'.

Harding believed the painted scene records the triumphant return from battle, because of the presence of animals, because the other human figures appear to be driven and unarmed [out of the twenty-seven figures shown in the White Lady painting only nine are armed], and because of the small group which faces the advancing retinue in an apparently welcoming attitude.

A tracing of the White Lady and accompanying paintings by Harald Pager clearly shows 'her' to be a man, as indeed are all the other human figures in the group. If Harding's suggestion that they represent an Ovambo ritual is correct, they would have been painted after the Ovambo farmers entered Namibia within the last 2,000 years. It is also possible that they represent a hunter-gatherer ritual that was later adopted by the Ovambo. Whichever scenario is correct, the saga of the White Lady remains a fascinating example of how important it is to see rock art through knowledge of the beliefs of the people who made it, rather than through the eyes of a transient European visitor with no experience of local customs. We can also ponder on whether the 'White Lady' site would receive as many visitors as it does today if the Abbe Breuil had correctly identified 'her' as 'him'.

→ Discover more about the Rock Art of Africa

→ Rock Art Network Colloquium - Namibia 2017

→ The Rock Art of Twyfelfontein /Ui- //aes, Namibia

→ The Damara People

→ Reflecting Back: 40 Years Since ‘A Survey of the Rock Art in the Natal Drakensberg’ Project (1978-1981)

→ Animals in Rock Art

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network