As part of the

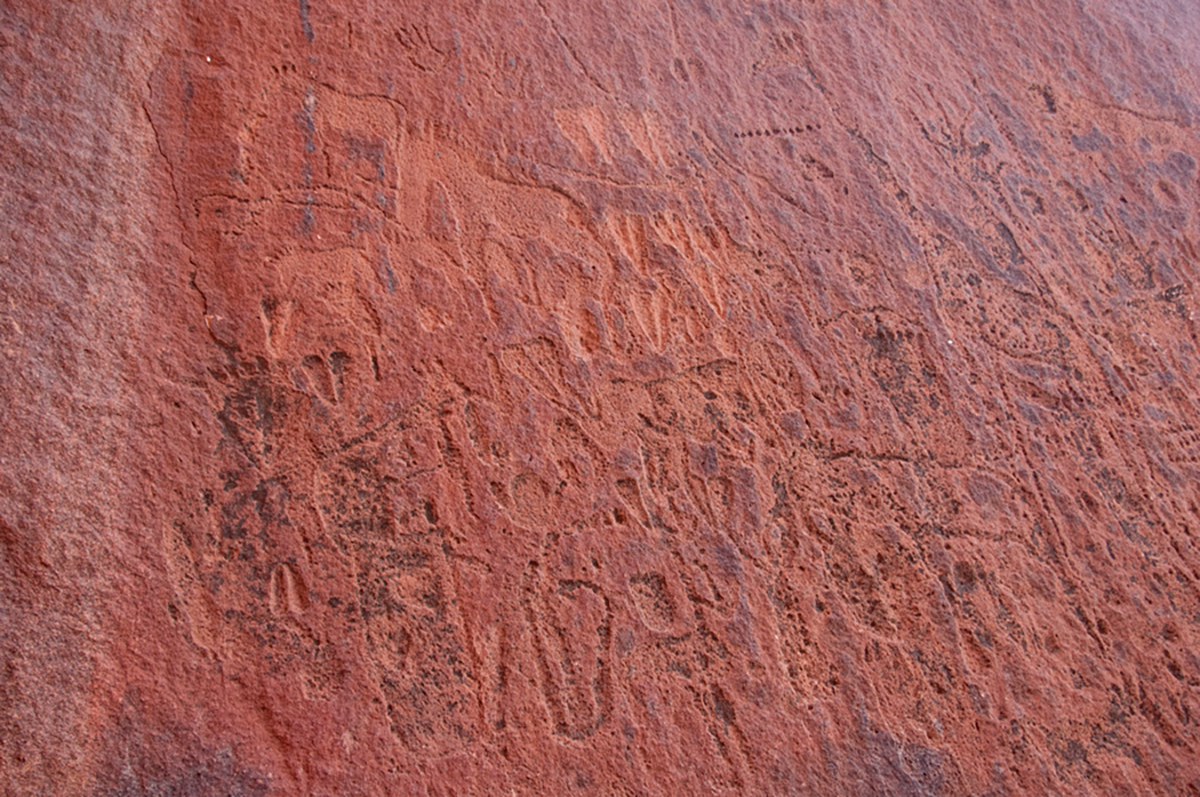

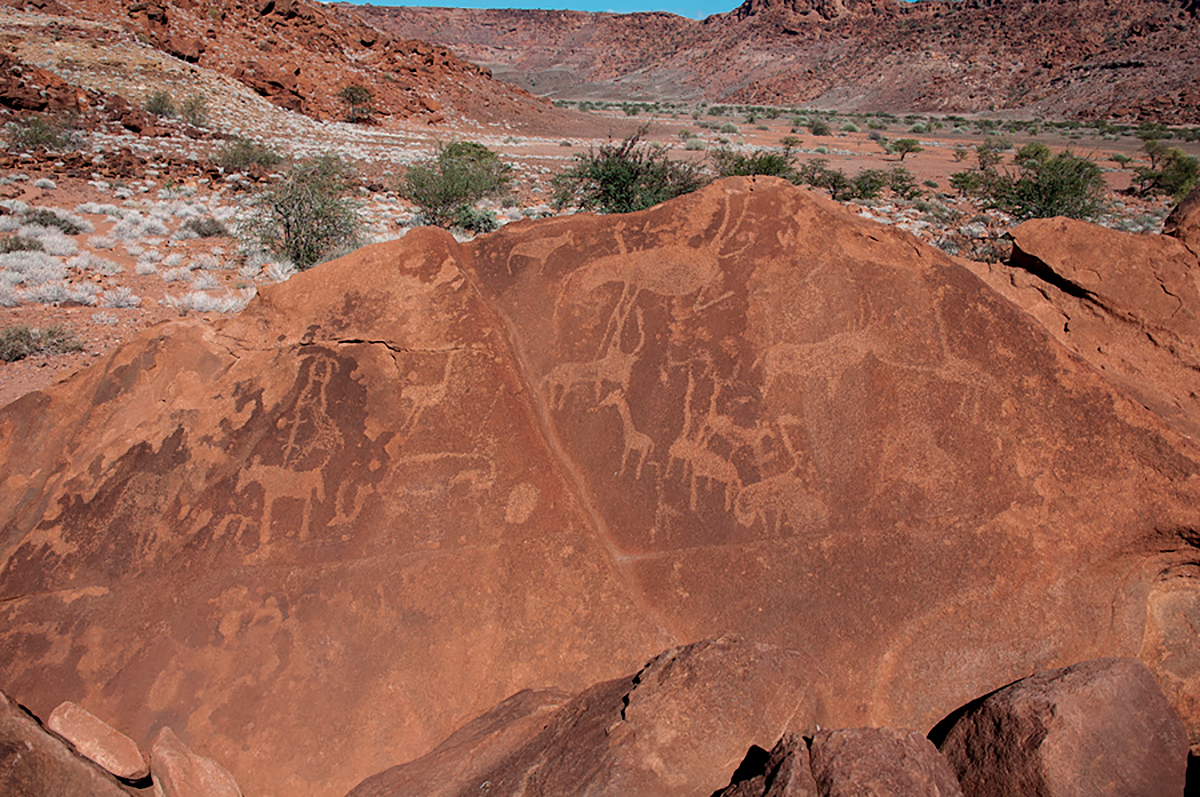

2017 rock art colloquium in Namibia organised by the Getty Conservation Institute, one of the rock art sites visited was the

World Heritage site of of /Ui- //aes, also known as Twyfelfontein in the Kunene Region of north-western Namibia.

Rock art played an important role in ritual practice among southern African hunter-gatherer communities. Painting and engraving traditions developed over the last 30,000 years into a highly sophisticated way of expressing complex beliefs about the supernatural world. The painted stones from Apollo 11 in Namibia date to roughly 27,500 years. However, there are no dates between Apollo 11 and the next oldest - around 10,000 years. It is estimated that the great majority of animal and human figures in southern African rock art were made within the last 7,000 years. The date for the art at Twyfelfontein is estimated to be around 5,000 years ago according to John Kinahan ('Spirit Rocks: the ancient art of /Ui-//aes' 2011) and the World Heritage dossier.

Paintings are generally found in rock shelters, often with archaeological evidence of human habitation. Engravings are generally found in the open, occasionally with occupational remains nearby.

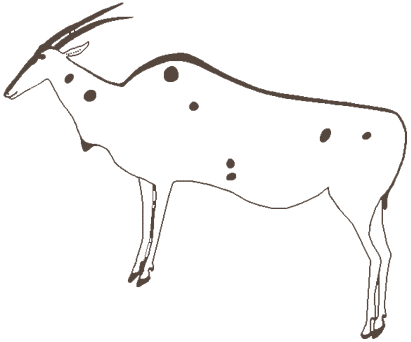

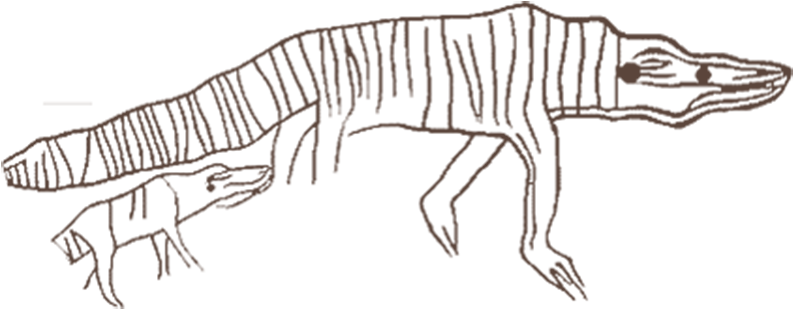

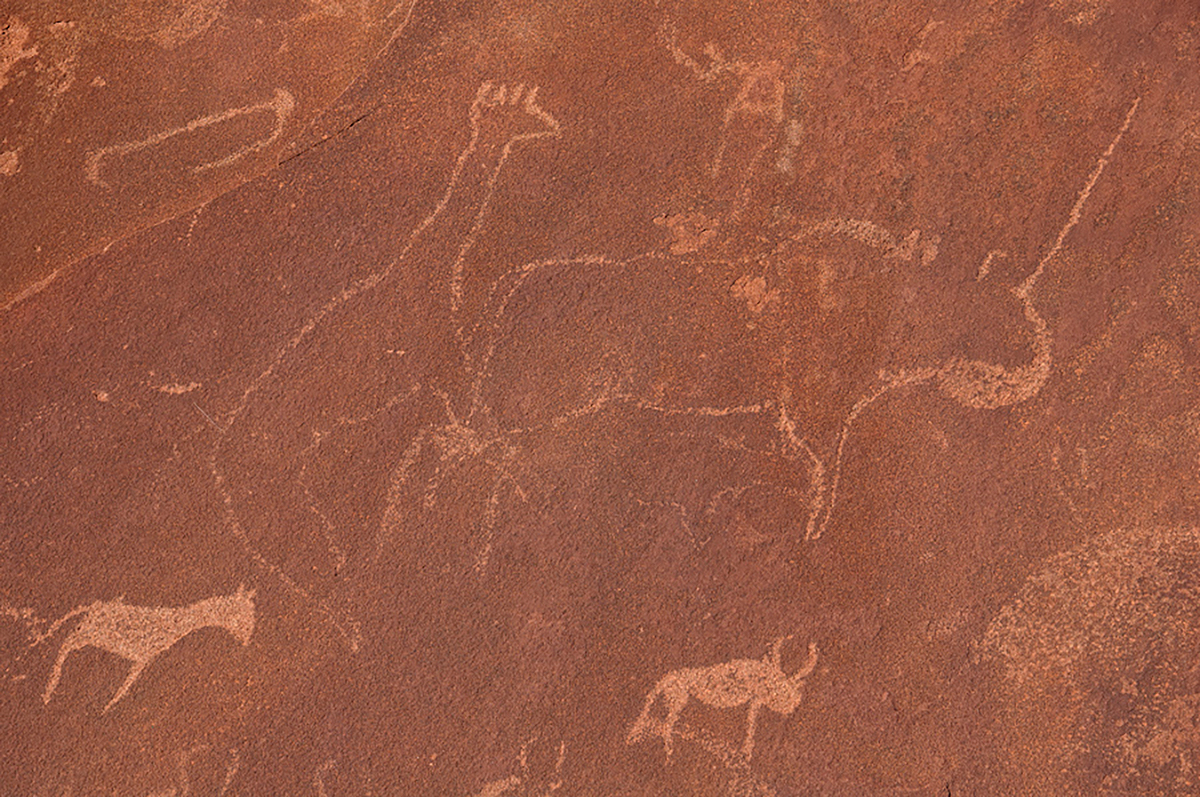

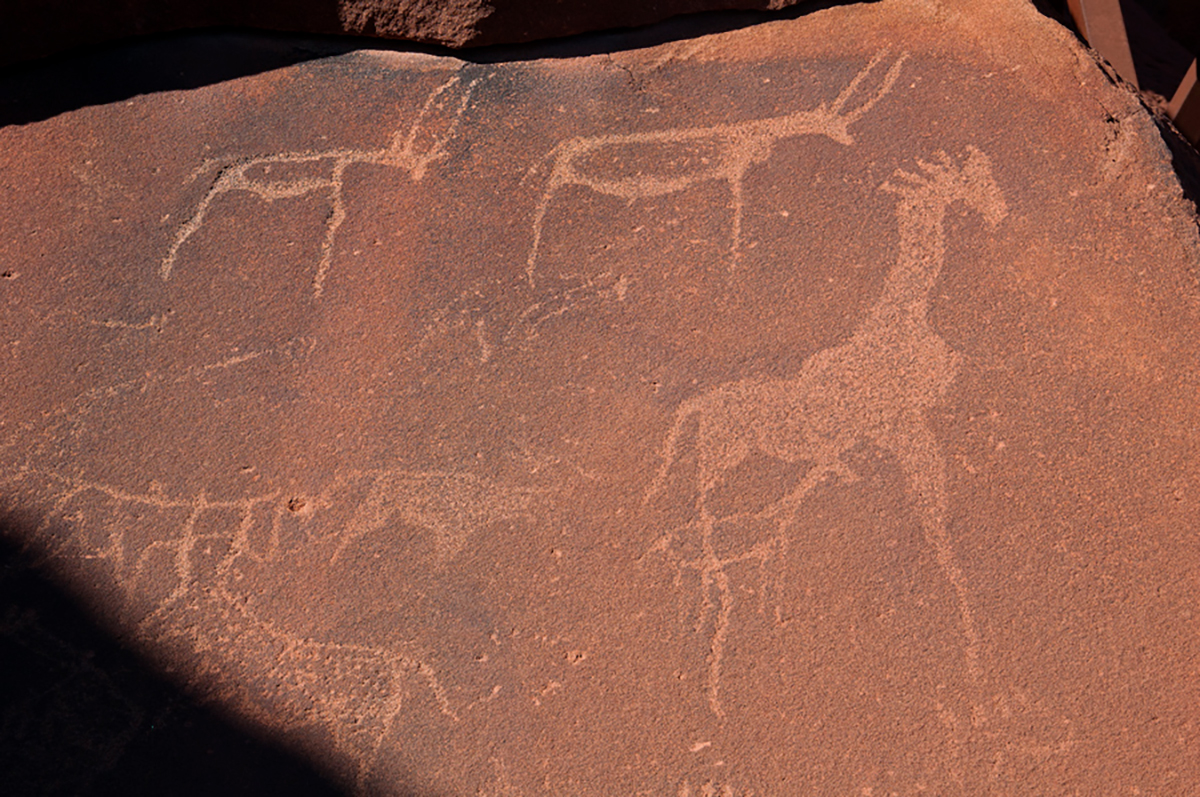

According to John Kinahan, most of the engravings at Twyfelfontein present the subject in broad, generalized outline. Animals are shown in profile, usually with both fore- and hind legs depicted. Another conspicuous aspect of the engravings is that they vary a great deal; some appear crude and unfinished, whilst others are highly worked and artistically accomplished.

Twyfelfonein sandstone is a hard, coarse-grained quartzitic material, and distinct engraving techniques have been identified by Kinahan:

Shallow pecking - most of the images are engraved by shallow pecking to define the outline, leaving the rock cortex intact in the case of an animal subject.

Deep pecking - which often creates a rough surface within the body of the engraving. Deep pecked images usually having more precisely defined outlines than the shallow pecked images.

False shading - a shallow type of engraving which removes only superficial cortex to create a colour variation in the body of the subject, as shown by the Lion Man engraving.

False relief - where the outline is deeply incised and the cortex removed to show the form of the subject, such as in muscle folds, to vivid effect in raking light. These techniques rely mainly on percussion, unlike the deep ground cupules which appear to have been made by rotating a sharp stone, possibly with the use of an abrasive. Abrasives are certain to have been used to create the unique flat polish effect seen in the Dancing Kudu.

A particular feature of the rock art of Twyfelfontein is its integration with the surroundings. The artists deliberately placed their art at significant points on the terrain. Some ar in cracks or fissures which served as entry points to the supernatural world.

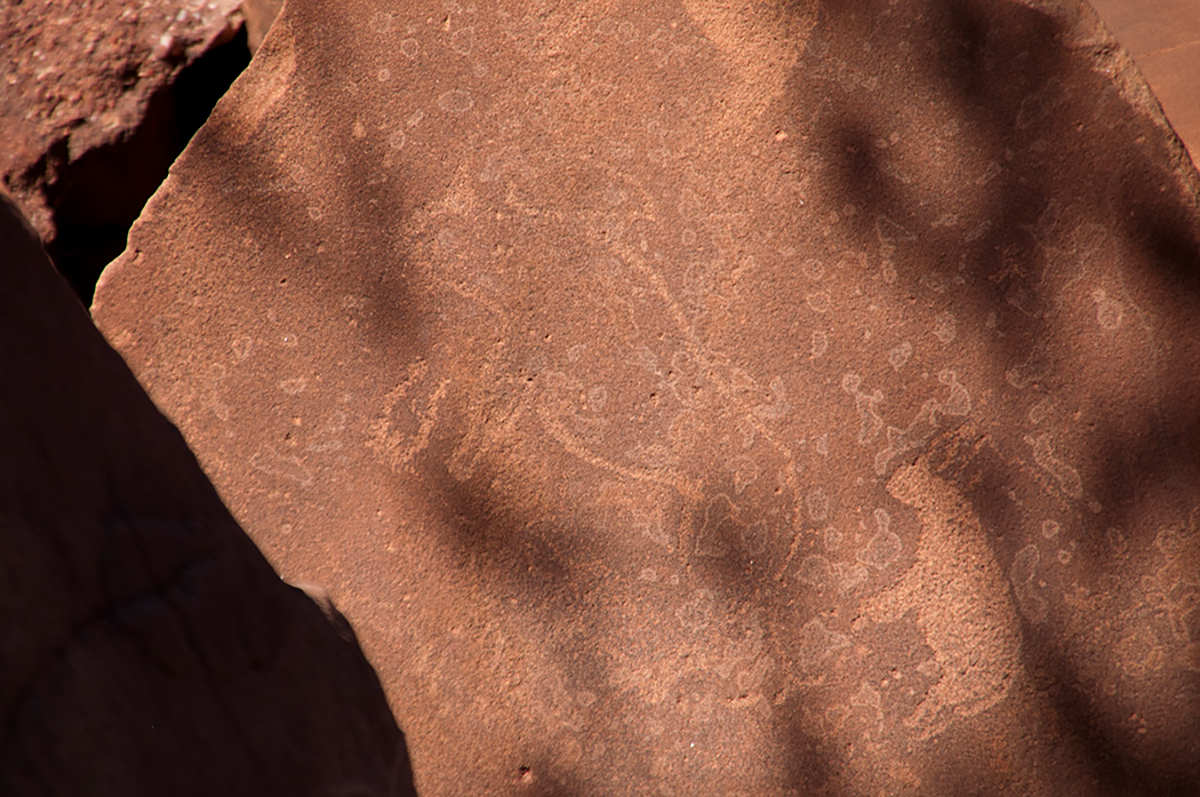

Some engravings - usually entoptic geometric patterns - are often associated with the 'edges' of rock faces. The edge is integral to the image, reflecting the trance and the edge of consciousness.

Photographsfrom from Twyfelfontein /Ui- //aes

UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Rock Art of Twyfelfontein Gallery presents the many facets that go to make Twyfelfontein, or /Ui-//aes, in Namibia one of the largest concentrations of petroglyphs in Africa. Most of these well-preserved rock engravings represent animals of various kinds. Geometric symbols as well as cupules are also heavily represented. The site also includes numerous rock paintings, depicting animals as well as human figures in red ochre. Artefacts excavated from two sites date from the Late Stone Age.

According to UNESCO, the site forms a coherent, extensive and high-quality record of ritual practices relating to hunter-gatherer communities in this part of southern Africa over at least 2,000 years, linking the ritual and economic practices of hunter-gatherers. All the rock engravings and rock paintings within the core area are the work of San hunter-gatherers who lived in the region long before the influx of Damara herders and European colonists. Apart from one small engraved panel which was removed to the National Museum in Windhoek in the early part of the 20th century, no panels of the Twyfelfontein rock art have been moved or re-arranged.

The Artists

Twyfelfontein /Ui- //aes - UNESCO World Heritage Site

The rock art at Twyfelfontein [Afrikaans for 'uncertain spring'] was probably produced during the dry season, and around 5,000 years ago when the climate was even drier than at present, because the shortage of water and food forced people to congregate near the spring. This then became a time of intense ritual activity.

Rituals helped to strengthen the values and cohesion of the group: they were performed during initiation into adulthood, to heal the sick, to ensure successful hunting, and to make rain.

The ritual traditions represented in the rock art of Twyfelfontein saw their greatest flowering during the last 5,000 years; a period of increasing aridity during which hunter-gatherer communities developed and perfected a wide range of economic survival strategies.

The rock art was the preserve of the medicine people, or shamans, and had 2 functions: as a means to enter the supernatural world - the spirit world - and to record the shaman's experiences in that world.

Travelling to the Spirit World

Twyfelfontein /Ui- //aes - UNESCO World Heritage Site

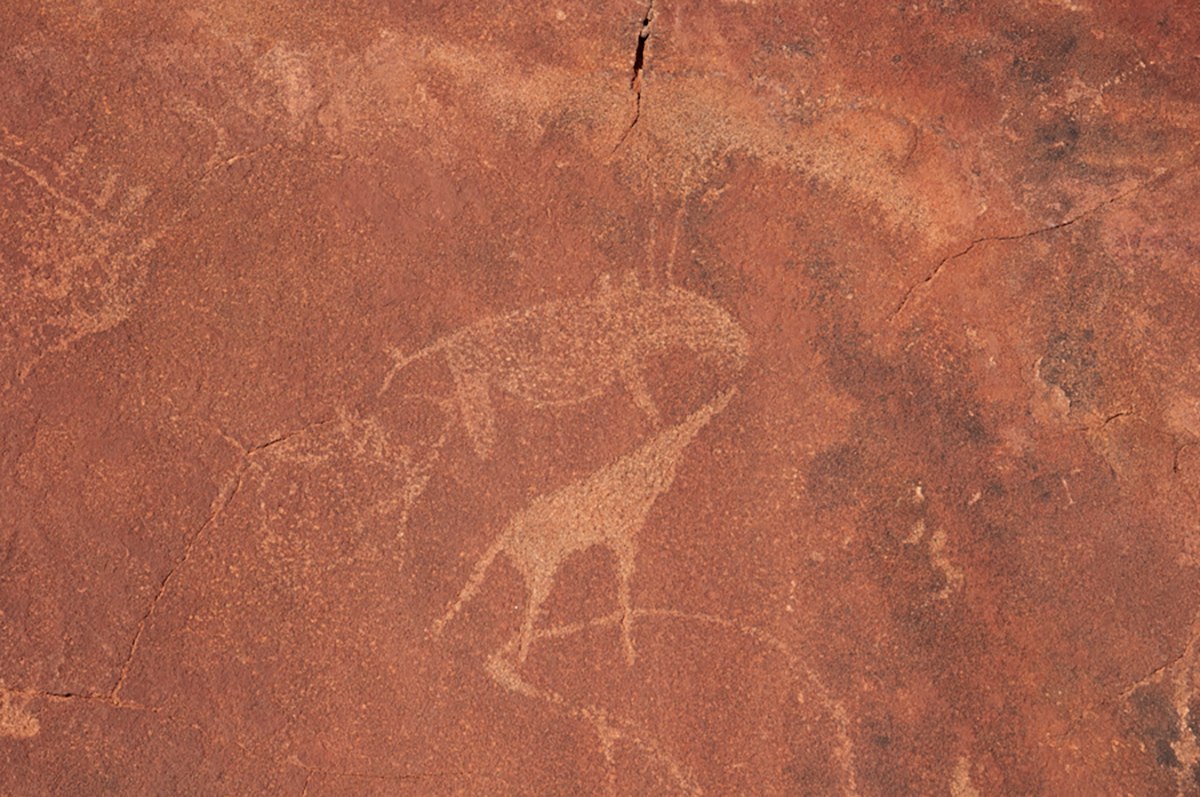

Giraffe near the Twyfelfontein /Ui- //aes site

The shaman prepared to enter the world of the spirits by achieving a state of trance, or altered consciousness. This could be done by dancing to rhythmic clapping or chanting, hyperventilation, dehydration, sensory deprivation or intense concentration. There is no evidence that shamans used drugs or other artificial means to induce trance, although this is possible. The shaman carried out important tasks while in the spirit world, such as healing the sick, making rain, and communicating with powerful spirit forces.

Leaving the body behind:

Giraffe are very common in the Twyfelfontein rock art, and characteristically shown without hooves, their legs tapering away in long thin lines. This represents the sensation of rising up into the air, as felt by the shaman in trance. Sometimes the giraffe body is shown distorted or hollow, as the shaman feels his shape changing. A shaman who has changed into a giraffe is shown with 5 protrusions from the head (right), representing the 5 digits of the human foot.

Giraffe are very common in the Twyfelfontein rock art

Perilous journey:

Entering into the state of trance, the shaman would experience a variety of physical sensations: he might feel as if his legs are growing unnaturally long, or that he is rising from the ground. He would shiver, and struggle to control his movements, sometimes collapsing on the ground with a gushing nose-bleed. This second stage of trance was known as the 'little death', the moment of entering the spirit world.

Taking on the form:

Following the death-like stage, the shaman would take on the form of a supernatural creature. This might be a familiar creature, such as a giraffe, elephant or lion, one that has special powers, such as to heal or make rain.This ability to enter the supernatural world and return alive was a rare gift, not possessed by everyone. Shamans were extraordinary men and women, who left an exceptional artistic legacy.

Transformation:

The rock art shows the moment of transformation from human to spirit animal through some of the signs of imminent death. Most common is the raised tail, shown in almost all the engraved antelope. The upright mane of the zebra represents the raised neck hair immediately before death. In these engravings, it is not the animal that is dying; it is the shaman in a death-like state as he is transformed into the animal.

Multiple Meanings

Twyfelfontein /Ui- //aes - UNESCO World Heritage Site

Each and every feature of an engraving is deliberate and holds a specific meaning. Sometimes the meaning is difficult to establish directly, but often an informed guess is possible. The 'Dancing Kudu' for example shows an obviously pregnant female. Kudu were valued as potent symbols of fertility and this may explain the choice of a kudu cow for the image. However, we cannot know all the multiple meanings that the images held for the artists and viewers.

Geometric symbols:

The shaman's vision became disturbed at the start of the trance; the shaman would see patterned flashes of light. Produced in the brain, these flashes are also known as 'entoptic' images. They are depicted in the seemingly abstract geometric patterns in the rock art. Meanders, dots, lines, grids, spirals and whorls resemble entoptic or inner-eye images recorded in neurophysiological experiments. Although entoptic images are similar for all people in the world, the associations formed in a state of trance are contextual. The shaman fuses the hallucinatory visions with images of animals and other potent spiritual symbols. It is possible that making the engravings helped to prepare the shaman for a state of trance. The repetitive chipping at the rock and the monotonous sound could have contributed to mental concentration.

Lion Man:

The 'Lion Man' engraving shows 5 toes on each paw - a lion only has 4 toes. The deliberate combination of human and animal features shows that this is a shaman who has transformed into a lion.

Hooves and feet:

Engravings of human footprints and animals may depict the moment of transformation from human to spirit animal. Sometimes the hoof prints of animals are shown with human footprints. On other occasions, the entire panel is devoted to the engraved spoor.

Birds:

Birds are prominent among the Twyfelfontein engravings, but do not include short-legged species that perch or hop. All the birds shown are species that stride, such as ostriches. The birds are often shown in a line, walking or dancing like people in the typical 'arms back' posture of ritual dance. Such images may represent people transformed into birds.