Chauvet's scarcity of human figures; why the rock art paintings and engravings of Palaeolithic Europe predominantly depict animals. Dr Jean Clottes mentioned to me recently that in all of the lectures he has given on the rock art of Chauvet, the most common question at the end is 'Why are there so few humans depicted?'

This is certainly the case for Palaeolithic Europe (although it does not apply to the rock art in the rest of the world) where human figures are relatively scarce; barely 20 complete human figures have been found in the whole of Upper Palaeolithic cave art. Handprints are common, as are symbolic depictions of genitalia, but not the whole figure. However, complete human depictions were being created in portable art - sculptures - rather than in parietal art.

Apart from their scarcity, the human figures of Palaeolithic Europe show 2 characteristics; they are almost always incomplete (a single part of the body) and unlike the animal depictions they are not particularly naturalistic. Note the human figure of Lascaux (below). Jean Clottes states that 'as the artists' abilities are beyond doubt, this must reflect a specific and intended style of representation, perhaps a consequence of taboos.'

At the time when the Aurignacian cave art of Chauvet was being created, over 30,000 years ago, there were not many humans and there were very many animals. The human to animal ratio was very low. The majority of animals represented in the cave art are large herbivores, the ones Palaeolithic people saw around them and hunted. It was the animals that took on a symbolic importance in the eyes of the artists, and it is here where we just touch on (the vast subject of) the 'composite' creatures depicted in rock art. In Chauvet at the very end of the End Chamber, on the hanging rock formation reaching down from the ceiling, is the image now known as the Sorcerer with the upper body of a bison and the slightly flexed legs of a human. Beside it there is drawn the front view of a woman's lower body (again, a partial drawing) with long tapering legs. Her pubic triangle and her vulva are depicted. The Sorcerer's figure folds around and faces in to the pubic triangle. This is a powerful composition, perhaps symbolising a relationship between a mortal woman and a supernatural animal spirit (top image).

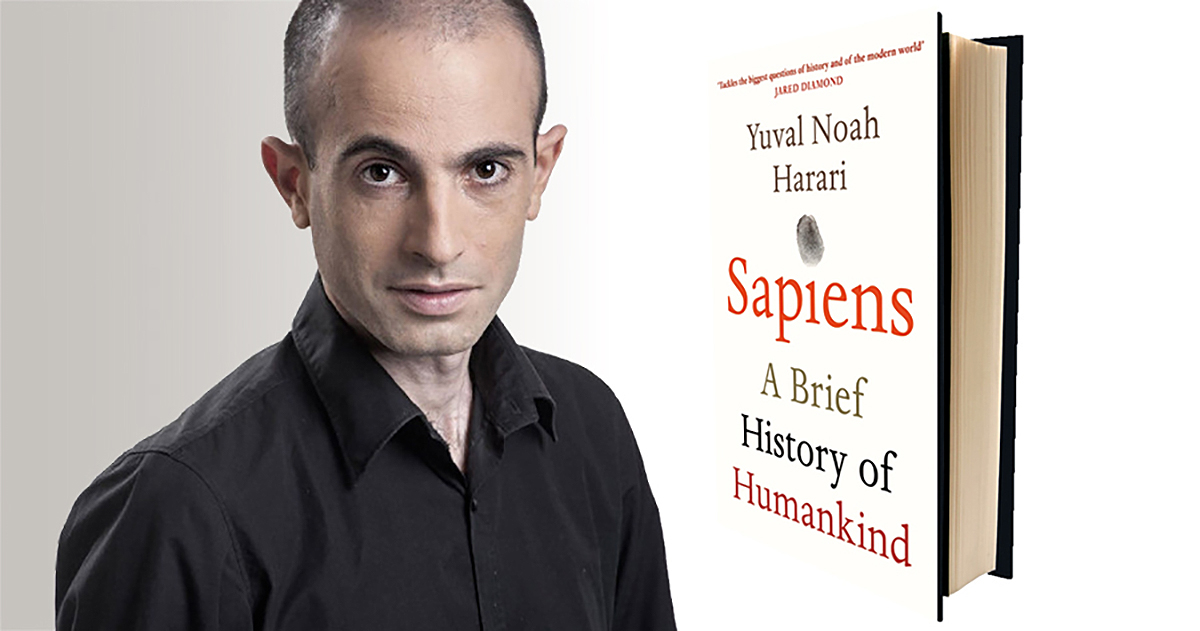

During the Palaeolithic 'animistic' beliefs were common; Yuval Harari describes this as 'the belief that every place, every animal, every plant and every natural phenomenon has awareness and feelings, and can communicate directly with humans.' Humans were within the landscape, but not the central element. Later, by the time we reach the Neolithic, humans had become so; the accent would shift and the human image would appear at the centre of their concerns. The transition from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic saw a change in concepts as well as a change in the role of art itself.

Palaeolithic life is described in Yuval Harari's publication 'Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind'. With his subheading 'The Original Affluent Society' he spells out some important facts:

'What generalisations can we make about life in the pre-agricultural world nevertheless? It seems safe to say that the vast majority of people lived in small bands numbering several dozen or at most several hundred individuals, and that all these individuals were humans. It is important to note this last point, because it is far from obvious. Most members of agricultural and industrial societies are domesticated animals.

'Members of a band knew each other very intimately, and were surrounded throughout their lives by friends and relatives. Loneliness and privacy were rare. Neighbouring bands probably competed for resources and even fought one another, but they also had friendly contacts. They exchanged members, hunted together, traded rare luxuries, cemented political alliances and celebrated religious festivals. Such cooperation was one of the important trademarks of Homo sapiens, and gave it a crucial edge over other human species. Sometimes relations with neighbouring bands were tight enough that together they constituted a single tribe, sharing a common language, common myths, and common norms and values.

'Yet we should not overestimate the importance of such external relations. Even if in times of crisis neighbouring bands drew closer together, and even if they occasionally gathered to hunt or feast together, they still spent the vast majority of their time in complete isolation and independence. Trade was mostly limited to prestige items such as shells, amber and pigments. There is no evidence that people traded staple goods like fruits and meat, or that the existence of one band depended on the importing of goods from another. Sociopolitical relations, too, tended to be sporadic. The tribe did not serve as a permanent political framework, and even if it had seasonal meeting places, there were no permanent towns or institutions. The average person lived many months without seeing or hearing a human from outside of her own band, and she encountered throughout her life no more than a few hundred humans. The Sapiens population was thinly spread over vast territories. Before the Agricultural Revolution, the human population of the entire planet was smaller than that of today's Cairo.

'Most Sapiens bands lived on the road, roaming from place to place in search of food. Their movements were influenced by the changing seasons, the annual migrations of animals and the growth cycles of plants. They usually travelled back and forth across the same home territory, an area of between several dozen and many hundreds of square kilometres.'

Visit the Chauvet section:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/chauvet/index.php

Visit the Lascaux section:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/lascaux/index.php

Visit the Art of the Ice Age section:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/sculpture/index.php

Read more about 'Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind' by Professor Yuval Harari:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/books/sapiens_a_brief_history_of_humankind.php

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 09 August 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 24 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 09 August 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 24 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

Friend of the Foundation