|

|

Ancient Symbols in Rock Art

|

Page 3/3 |

Visual Hallucinations

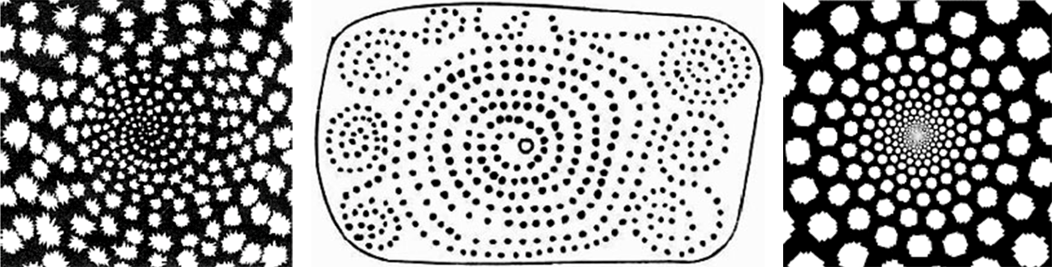

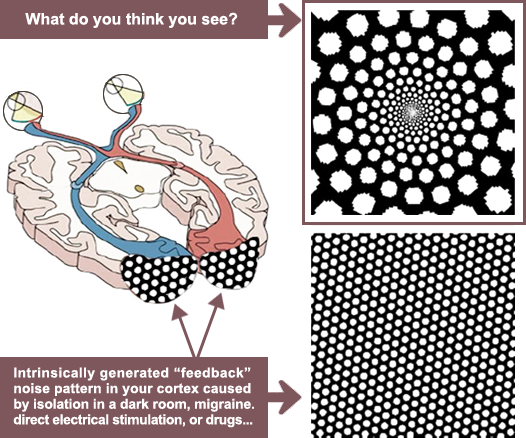

The geometric forms seen in visual art - in art of great antiquity - are equivalent to the patterns seen as visual hallucinations during migraine headaches, during prolonged visual deprivation, during 'near death experiences', after ingestion of psychedelic drugs, or during direct electrical stimulation of the brain. Modern experiments show that these geometrical forms emerge from the characteristics of the human brain.

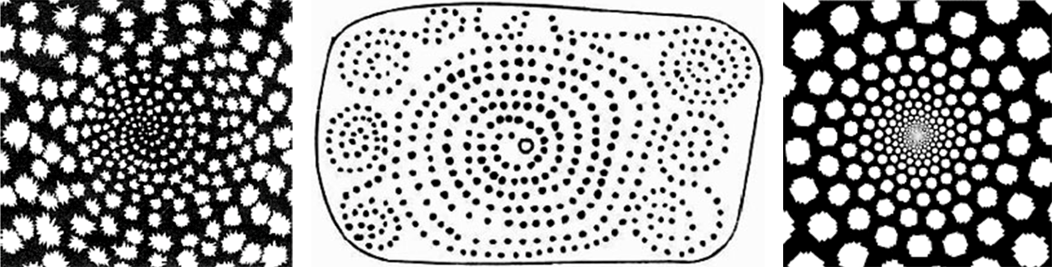

left 1. Hallucination drawn by a subject using LSD (from Siegel, 1977).

middle 2. Mammoth ivory plaque presumed to be a belt clasp. The spiral converges to

a hole through the centre. Dated at 16,000 BCE from Mal'ta on Lake Baikal Siberia.

right 3. Predicted Hallucination from a mathematical model by Bressloff et al.

The universal geometric motifs emerge from activity in what is known as the primary visual cortex of our brains. This is the very first stage of processing, where the information captured by our eyes enters the cortex of our brains. The geometric forms can be perceived directly during hallucinations, and this supports the hypotheses by Heinrich Klüver, David Lewis-Williams and Jeremy Dronfield, that rock paintings by shamanistic artists are simply an accurate record of the artists' visions: the artists could have been drawing what they were seeing, in a very literal sense. It is possible that these geometric motifs are infact 'natural motifs' for our brains. We are now in the realm of 'geometric neuro-aesthetics'.

Most people will be able to notice patterns with careful concentration under the correct conditions. When the eyes are closed, many very dim images will be perceived, such as a ripple pattern. These ripple patterns are known as 'drug-free hallucinations', and emerge from the baseline activity of the part of the human brain that mediates the visual perception.

Other examples of drug-free hallucinations are the dynamic, jagged geometric patterns called 'fortification patterns' that often accompany migraine headaches. The image of jagged patterns around a dark visual 'hole in the universe' bears a striking resemblance to the manner in which the entry portals into the Passage tombs in Ireland were decorated. The decorated lintel stones placed over the dark entrance tunnels into the tombs may be a direct representation of patterns seen by the artists. Are there hallucinations that correspond to the other geometric forms besides those induced by migraines?

LEFT

Top. Fourknocks, Central Recess Lintel. Middle Top. Fourknocks, West Recess Lintel.

Middle Lower. Fourknocks, Entrance Lintel. Lower. Newgrange, Corbel in Chamber.

RIGHT

Fortification patterns recorded by migraine sufferers.

A Cerebral Source

Is there an underlying source to account for this geometric universality? Not a supernatural source, but a cerebral source, where the images emerge naturally from the structure of the brain, and work their way into all visual art forms, even those that do not involve drugs or hallucinations.

Neuroscience research reveals that these geometrical forms emerge from the characteristics of the human brain that we all share; characteristics of the human brain that were established by our hominid ancestors hundreds of thousand years ago.

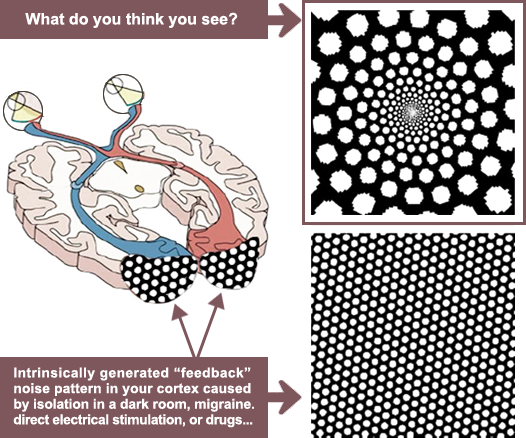

Nerve cells from the eyes connect to the cortex in the back of the brain and form a distorted map of what is being seen. A neuroscientist named Eric Schwartz studied the nature of this distortion, and showed how to transform any visual scene, for example, a face, into the pattern of activity it would generate in our visual cortex. This is a two-way process: the model can predict what you are seeing, based on the activity pattern that is generated back in the cortex.

So how does this relate to universal geometrical motifs?

Bressloff et al. model

Based on extensive research about the properties and interconnections of the nerve cells in our visual system, neuroscientists can now predict the activity patterns that would be generated in the visual cortex in response to hallucinogenic drugs, near-death experiences, migraine headaches, or prolonged isolation in the dark. Professors Bard Ermentrout and Jack Cowan showed that those conditions would lead to frenetic brain activity, rather like the audio feedback generated by a microphone placed too near to the output speakers of a high-gain PA system. Dr. Cowan, Dr. Paul Bressloff and several of their colleagues extended the earlier models, and derived a whole set of cortical patterns can be matched to the visual hallucinations that would be perceived during that activity.

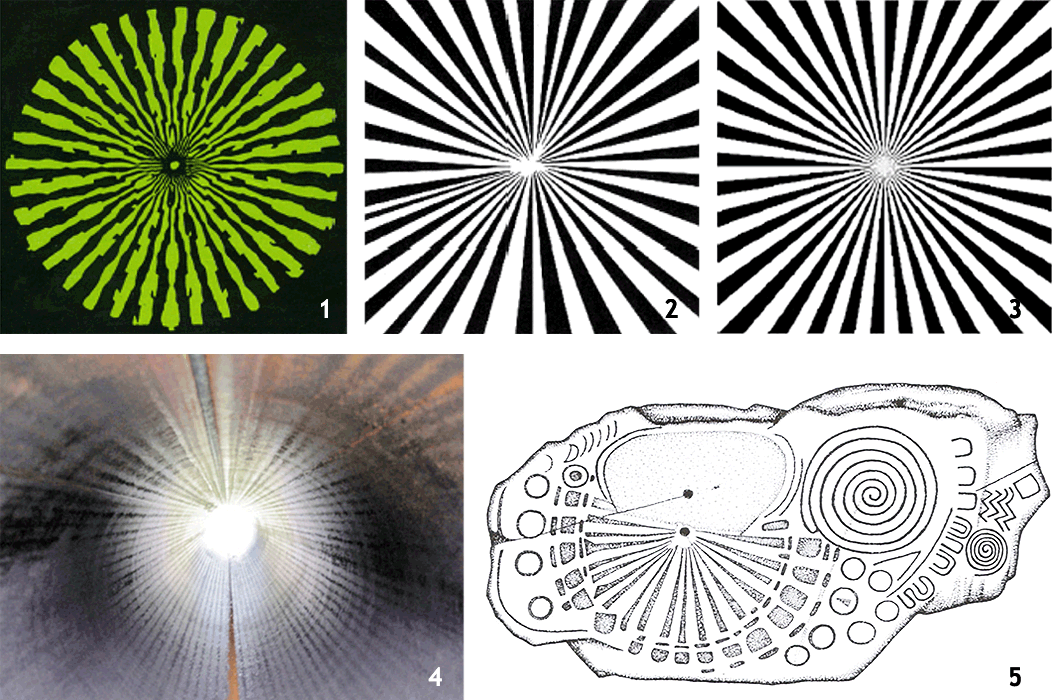

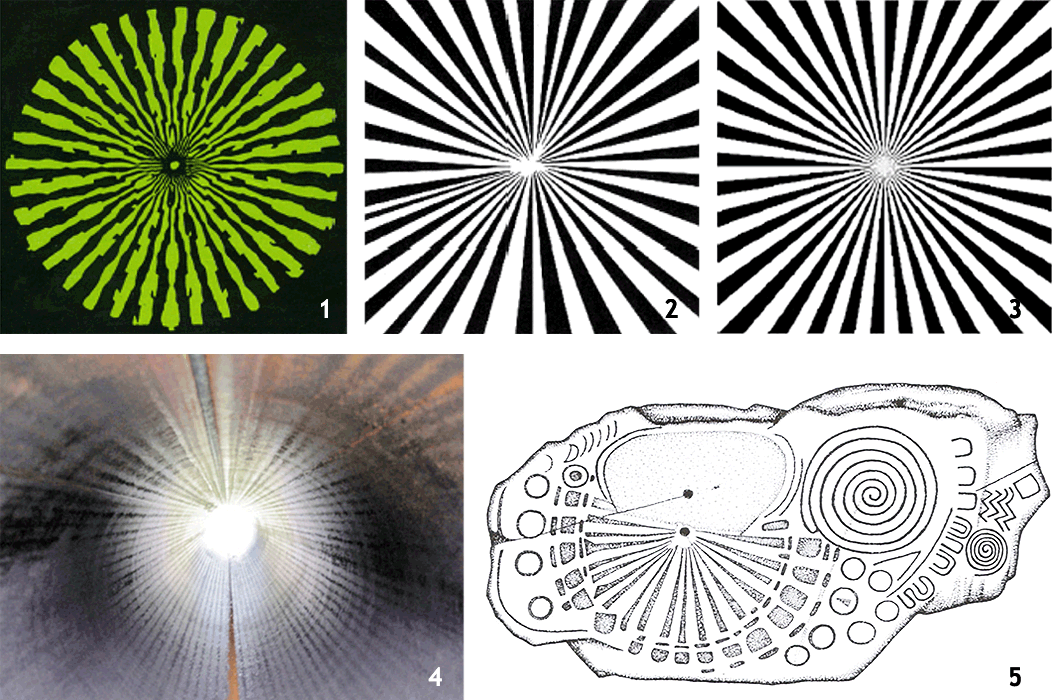

These predicted hallucinations are very similar to the real, recorded hallucinations. Therefore a plausible hypothesis may be that prehistoric rock paintings and geometric art forms are simply an accurate record of the artist's vision. However, was the artist who created the 18,000 year-old mammoth ivory plaque from Siberia doing so under the influence of drugs, migraines or near-death experiences, or was this simply a pleasing and meaningful pattern? Similarly, the predicted hallucination ray patterns that come out of the computer model of the visual cortex bear a striking resemblance to the prehistoric engravings on one of the Knowth kerbstones.

TUNNEL HALLUCINATIONS

1. LSD hallucination, from Oster (1970). 2. LSD hallucination, from Siegel (1977).

3. Predicted hallucination from mathematical model by Bressloff et al.

4. Image representing a person's near-death vision.

5 . Megalithic kerbstone from Knowth, Ireland.

Conclusion

In the eternal question of what inspires art, modern science may appear to have some answers. But can this modern approach unlock the secrets of a prehistoric past? Can they determine the influences of ancient artistic endeavour?

It is possible that the geometric motifs appear in the art of hallucinators as well as non-hallucinators; for the latter because these forms are 'natural motifs' for our brains. The geometric motifs that occur most frequently in works of art that we consider pleasing may be the ones that activate the natural baseline activity modes of the visual cortex: they may be more effective at stimulating a large-scale pattern of activity in the visual cortex, and more aesthetically pleasing than motifs which do not correspond to the intrinsic patterns of activity.

Therefore it is the structure of the visual cortex which might explain some fundamental shared aspects of our artistic aesthetics.

→

Bradshaw Foundation